Among the many striking images from the pandemic is an aerial photo showing cars in seemingly endless rows lined up at a food bank in San Antonio, Texas.

A jarring awareness of food insecurity in the U.S. has accompanied the health and financial concerns brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, with record numbers of people visiting food banks for the first time.

Even those not immediately in need were made increasingly aware of food insecurity in 2020, amid conversations not only of the economic fallout of the coronavirus, but also how structural racism has disproportionately left Black and Hispanic households at risk.

This conversation is overdue. Long consumed with the obesity epidemic, Americans have found it harder to grapple with the issue of food insecurity as a wealthy nation.

As a researcher of food policy, I have seen how people have focused more attention on addressing the issue of food insecurity in recent years. In 2000, just seven research articles with “food insecurity” in the title or abstract were listed in the leading database of biomedical literature. The total rose to 137 in 2010 and to 994 by 2020.

I am currently conducting the first National Institutes of Health-funded study of the charitable food system, which includes food banks – nonprofits that procure, store and distribute food, usually to smaller agencies – and food pantries, which distribute food directly to households that need it.

Although awareness of food insecurity is growing, it is important to understand what is meant by the term and how it fits with other food access concepts, such as hunger and food sovereignty.

What is Food Insecurity?

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture), food insecurity occurs when households are unable to acquire adequate food because they have insufficient money and other resources.

Food insecurity is measured at the household level and reflects limited access to food. This makes it different from hunger, which is a physiological condition experienced by an individual. The USDA does not measure hunger in the U.S. Instead, the agency sees it as a consequence of people having limited access to food.

The USDA has measured food insecurity for 25 years. This metric captures both the uncertainty of not knowing where one’s next meal is coming from and the disruptions of normal eating patterns and reductions in food intake.

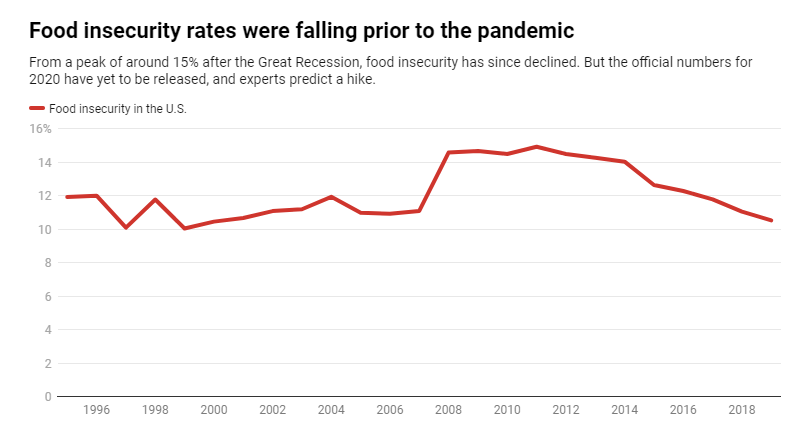

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of food insecurity peaked at just under 15% of households in 2011. Rates then steadily declined each year through 2019, when just over 1 in 10 households reported experiencing food insecurity.

But then came 2020.

Although official statistics have not been released yet, early evidence suggests that food insecurity rates hit unprecedented levels, affecting perhaps 17 million more Americans than in 2019. Households with children were struck at alarmingly high rates, exacerbated by the closure of schools and child care facilities. In particular, Black and Hispanic families with children were disproportionately affected.

Food Justice, Sovereignty and Apartheid

That Black and Hispanic households were hit the hardest by food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic is part of a bigger picture. Food insecurity is fundamentally an issue of health equity – the fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible without facing obstacles like poverty and discrimination. Even in normal times, food insecurity disproportionately affects low-income households, Black and Hispanic families, female-headed households and families with children.

Families struggling with food insecurity face not only insufficient food, but also insufficient nutritious food. Because of this, people who are food-insecure have higher risks of a range of diet-related chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

Food insecurity can be exacerbated by living in low-income areas without access to sources of healthy and affordable food. These areas have often been referred to as “food deserts,” although this metaphor is being phased out by food justice advocates, researchers, and government agencies.

Another term that has emerged – “food swamp” – describes neighborhoods where sources of unhealthy foods outnumber sources of healthy food – for example, the number of fast-food outlets outnumbers grocery stores.

Meanwhile, several other terms bring civil rights into U.S. urban food activism. “Food justice” is a food movement rooted in addressing class and race issues, often through local community food production. “Food sovereignty” originates from indigenous and global agrarian communities, and refers to the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

Another term, “food apartheid,” even more explicitly identifies structural racism as a root cause of food-related inequalities.

What these terms – food sovereignty, food justice and food apartheid – have in common is that they prod citizens, researchers and policymakers to move beyond issues of geographic food access and “how to feed the poor” and instead focus on how food systems can be reformed to address fundamental causes of food insecurity and health inequities.

A New Era

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration tightened restrictions on SNAP benefits. Formerly known as food stamps, SNAP is the largest of the federal food programs, providing monthly benefits to supplement the food budget in income-eligible families. Food insecurity was a critical part of policy discussions of SNAP restrictions.

But the issue of food insecurity has seemingly seeped more broadly into the public consciousness in conversations about racial justice, economic hardship, school reopening, pandemic preparedness and the food supply chain that ramped up in 2020 – conversations that are continuing in 2021.

The recent rise in food insecurity has prompted a response that has at times overwhelmed food banks and food pantries and the providers of free meals. But more sustainable solutions, such as anti-poverty policies, are needed to address the problem’s root causes.

Food insecurity is not a new problem, but the current challenges come in an era in which more people are aware of the problem. My hope is that the long-overdue public exposure of America’s fault lines can be the catalyst for new efforts.

Originally published in The Conversation.