Psychological trauma results when we are forced to endure something unendurable, in a hopeless position where we can neither fight nor flee, something like being trapped in an elevator with a grizzly bear. The Covid-19 pandemic has been, in effect, a slow-motion traumatic event, except the grizzly bear is invisible, and he’s everywhere. We can’t fight the virus, we can’t run away or hide from it, and we can’t deploy the third line of defense by banding together for protection, the way social animals do instinctively, because only distancing keeps us safe.

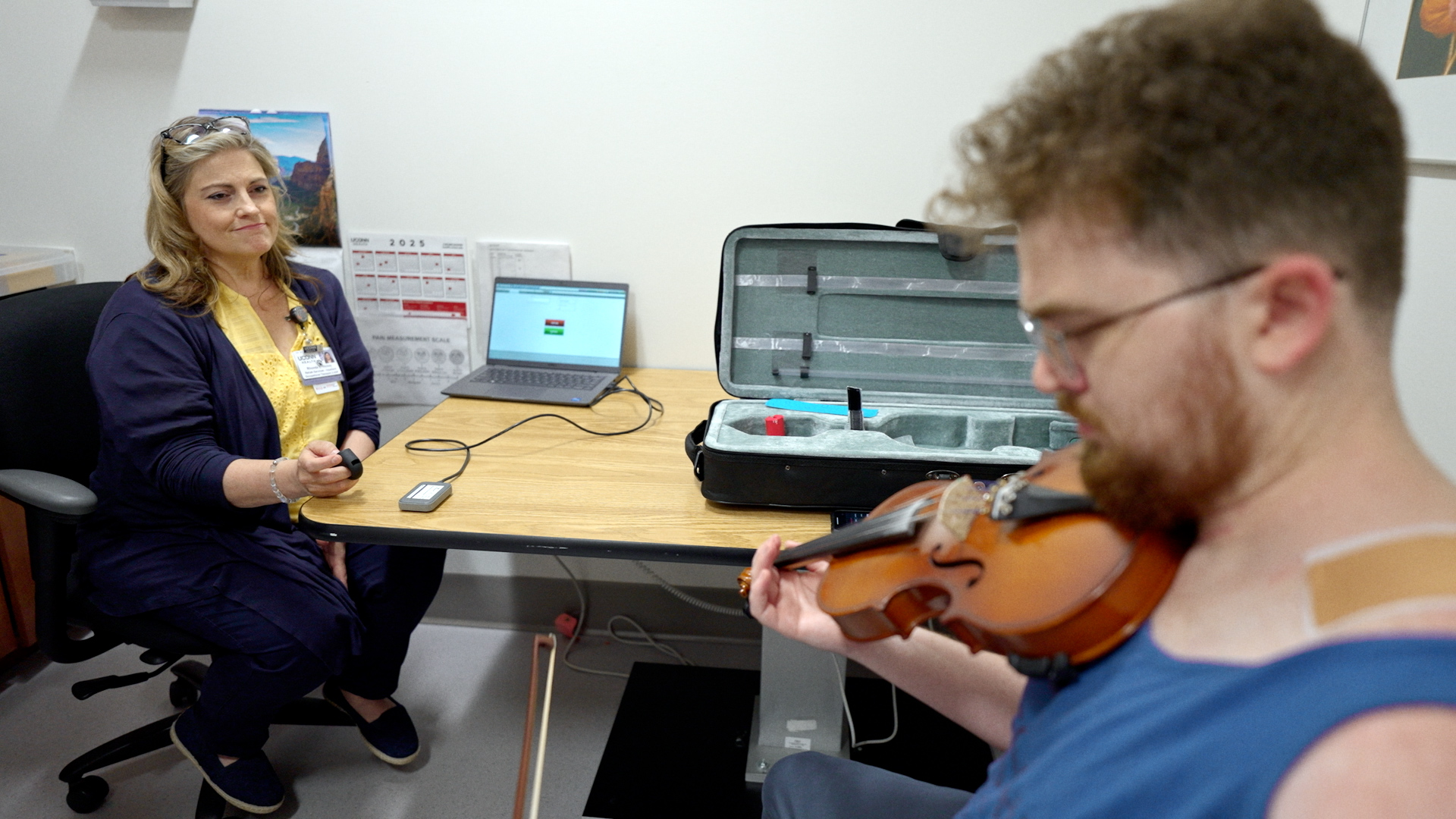

Covid presented Dr. Neha Jain, assistant professor of psychiatry at the UConn School of Medicine and director of telehealth services for psychiatry at UConn Health, with a problem unlike anything she’d ever encountered. How do you provide psychiatric care to patients who are unable to come in to receive it?

The answer was telehealth, but putting that in motion was a bit like building an airplane while you’re flying it.

“We were doing a very small number of telehealth visits even before Covid, but once it hit, we moved fast,” says Jain. “We shifted into high gear. The biggest problem was the buy-in, convincing people to use it. That required education and outreach, both for providers and patients, as well as IT support.

“The more I talk to people, the more I realize how extraordinarily smooth our transition was,” Jain says. “By March 16, 2020, most of us had gone virtual. We typically have about 3,000 visits a month, to about 100 doctors, therapists, social workers, trainees. Most people will see an average of 5 to 15 patients a day, typically anywhere from 150 to 200 a day total.”

Numbers for nonessential hospital visits nationwide dropped at first, with people knowing only that they were safe if they stayed home. Once telehealth

became widely available, the patients returned. But for UConn psychiatry, numbers remained steady due to the team’s rapid and smooth transition, Jain says.

“We had 170 virtual visits today and about 20 in-person visits,” right in line with the pre-pandemic average, Jain said in January.

The initial introduction period involved some trial and error. Not everyone had the technology, or a space where their privacy was assured. Some people met with their therapists using their smartphones while sitting in their cars. Some patients were hard of hearing, while others had language barrier issues and needed interpreters. Some simply wanted to meet in person. Jain and her clinicians scrambled to accommodate everybody. The transaction itself remained consistent. Of all the medical disciplines, psychiatric treatment relies primarily on verbal communication for diagnosis and treatment, and as such might be the most amenable to video-conferencing.

“The basic question,” says Jain, “was, can we get enough information from the patient to come up with a treatment plan? What’s going on with them? What do they need? I can do that on a video visit. Everything else changes. Now the patient is at home. That can both add challenges and create opportunities.

“It’s much easier now for me to get information from family members, because they’re right there. On the other hand, there are situations where you may have to reestablish some boundaries. For the provider, it’s very tiring, because now, you’ve got the patient in this little window, and they’ve got you in this little window, so we really hyper-focus. Almost everybody finds it more exhausting.”

Reaching More People

When you’re working screen to screen instead of face to face, the empathetic conversation suffers. Sometimes it’s the loss of human connection that drives people to seek help in the first place; even so, telepsychiatry has compensatory strengths.

“The day I approached the idea of video visits,” Jain recalls, “some of my colleagues were saying, ‘We can’t do that — I need to see my patient in person.’ On

day three, they came back and said, ‘I’d rather do video, because in person, I have a mask and a face shield on, and my patient has a mask on, and I can’t tell a thing, even when I’m in the same room. I’d much rather be on video and be able to see their full face.’ These are things we didn’t predict. We learned on the fly.”

“In many ways, telepsych has helped people to connect more,” says Stephanie Paul, LCSW, UConn Health’s Behavioral Health Intensive Outpatient Program manager. Paul works with people in crisis: people whose lives are destabilizing, who are suffering from multiple mental health issues including depression and anxiety, as well as addiction, who might benefit from group therapy.

“When we were meeting in person we would have people who struggled to make it to group. It was too much for them, sometimes due to physical limitations, or they became overwhelmed with anxiety at the thought of coming into the physical group space. People would set up an appointment, but they wouldn’t show,” Paul says. “When you remove that barrier, you can reach more people than you ever could before. You are not limited to your local three-town radius, both to reach patients and to provide a specific kind of support group.”

Different populations respond differently to telepsych. Jain’s clinical work is primarily geriatric, servicing a demographic likely to find the technology disorienting but not necessarily more than in-person visits requiring them to leave their homes, get in a car, drive to the clinic, climb a flight of stairs, and be checked in at the office.

“If they have advanced dementia,” Jain says, “all of these things are very disorienting for them. Sometimes when they are at home, and they are in a familiar comfortable space, it works better.”

Dr. David FitzGerald, assistant professor and director of UConn Health’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic, addresses a younger population sometimes described as “digital natives,” familiar (some might say too familiar) with screens and webcams.

“Generationally,” FitzGerald says, “they’re more comfortable with that. In terms of a particular teen, or child, the presentation can vary. We have kids who are socially anxious and have difficulty being on the screen. For them, we might have them gradually increase the amount of their face on camera while using some of the coping skills they are learning.

“It’s also important to establish that patients have a private space that’s not accessible to other people. If you have a house, all one floor and open, and a kid’s trying to have a conversation that’s private, some things can be more difficult, situations where someone could be just out of frame, and we can’t see. In contrast, there are certainly times where, if a teen is having a problem with a parent, it might be helpful to have time to have both together, to help them work it out if they can’t do it on their own.”

Video conferencing can also work better than seeing a masked doctor in person for kids on the autism spectrum who have trouble reading emotions.

“For kids who struggle with those kinds of communications,” FitzGerald says, “it would be even more difficult if you obscure half of the field of what they can choose from for information. That might be a reason to emphasize the opportunity to do something virtually.”

Paul facilitates therapy for groups of people 18–55 years of age and for adults over 65. Anyone who has done a Zoom meeting in the last 12 months knows how hard it is to coordinate and regulate more than a few people on the same screen. Group therapy can be difficult.

“We anticipated there would be issues,” says Paul. “We tell the group members what the guidelines are, and there are still people who struggle with it. We will often say, ‘We’re going to ask you to mute yourself, and if you’re having difficulty with that, we can help and do it for you.’

“Sometimes people have a lot of anxiety, when they’re first starting, if they haven’t had the online experience yet. So we reach out ahead of time. I send the whole group an email, welcoming them, with some tips on how to participate. If there are any issues, or people are having difficulty getting on, we have a system within our team where one person will call them, and we’ll walk them through it,” she says. “But the sessions are interactive, so we encourage group participation. A day or two in, most people get comfortable with the platform, and there’s a good flow of discussion going on that starts to occur and is therapeutic.”

Stepping up for Survival

Dr. Surita Rao is program director of the psychiatry residency training program at UConn Health, in charge of training doctors to specialize

in psychology. She is proud of the residents for how they stepped up and adapted, suddenly forced to take on more responsibility than usual. In her clinical practice, working with people with substance abuse issues, she has found that some of her patients also have stepped up as a result of the pandemic, although the national trend is that patients with substance use disorders are struggling to remain in recovery.

“A lot of my patients have been doing really well,” Rao says. “For some people, the lockdown has actually helped them to build up more sober time than

before. One person said it gave her a chance to really reevaluate her life and ask herself, ‘Do I really want to be using, or sober?’ For people who have a lot of social anxiety, experiencing stress from going into work or interacting with other people, working from home has helped them maintain sobriety.”

While there are silver linings, however, concerns about isolation due to pandemic precautions persist. If we didn’t know it before, we know now that living apart from each other runs contrary to human nature. Some people have continued to socialize, fully (and not-so-fully) aware that they are putting themselves and others at risk. Telemedicine can mitigate and remediate the isolation we have all felt during quarantine.

“One of the big concerns, in the beginning,” says Paul, “was the isolation. We didn’t want the people who we’re treating to sink further and further into isolation. Even though you’re on a screen, you’re still seeing people every day, and you’re still able to talk about what you need to talk about.”

Psychotherapists are required to give their patients their undivided attention, which can be a challenge when you’re working from home, with young children in the next room trying to attend remote school, or dogs barking in the background. Such issues tend to resolve themselves over time as everyone finds a routine that works, according to the UConn team. As both providers and consumers grow more familiar and more comfortable with telepsychology, it seems telemedicine, while it will never replace face-to-face meetings between doctor and patient, will nevertheless remain an option for any standardized treatment plan. As Paul says, “That genie is out of the bottle.”

Surviving the pandemic, without dismissing the widespread grief it has caused, has also reminded all of us how resilient we can be.

“People need a purpose to live and a higher goal,” Jain says. “Denying that, we become depressed. Folks feel a sense of purpose by connecting to their community. Loneliness draws us to each other. But we know wellness is impacted by one’s capacity to be grateful. That’s what I’m seeing now.

“It shocks me, when I’m talking to people who haven’t seen me in six months, and they’ll say, ‘I’m so grateful that you’re healthy, and my family’s healthy, and I can talk to you.’ I’m seeing them relying so much more on gratitude. I’ve seen them relying so much more on their faith. When we have a collective trauma, there is that sense that to survive, we need to help each other. We need to come together in some way.”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of UConn Health Journal. View the full issue.