As school leaders head into this fall, ensuring that students as well as staff have social, emotional, and behavioral support is top of mind after an academic year marred by major disruptions — from losing valuable in-person classroom time to enduring the stress, uncertainty, and tragic loss caused by the pandemic.

This summer, the Center for Education Policy Analysis, Research, and Evaluation (CEPARE) at UConn’s Neag School of Education convened more than 50 principals, assistant principals, educators, and school district leaders from across the state of Connecticut to coach them on fostering social, emotional, and behavioral well-being and safe school environments.

This summer, the Center for Education Policy Analysis, Research, and Evaluation (CEPARE) at UConn’s Neag School of Education convened more than 50 principals, assistant principals, educators, and school district leaders from across the state of Connecticut to coach them on fostering social, emotional, and behavioral well-being and safe school environments.

Held virtually, this Social, Emotional, and Behavioral (SEB) Leader Academy featured experts from UConn’s Collaboratory on School and Child Health (CSCH) sharing insights on strengthening policies and practices in support of SEB well-being at attendees’ schools going forward.

Two Neag School alumni — East Hartford superintendent Nathan Quesnel ’01 (ED), ’02 MA and Vernon superintendent Joseph Macary ’94 (ED), ’08 ELP, ’16 Ed.D. — designed the Academy in collaboration with CSCH Director and school mental health expert Sandra Chafouleas and CEPARE Director Morgaen Donaldson.

It is the first in a series of academies that will be offered free of charge to select school districts in Connecticut.

According to Chafouleas, who facilitated the SEB Leader Academy sessions with CSCH staff, the decision to focus with school leaders on the topic of SEB well-being was intentional.

According to Chafouleas, who facilitated the SEB Leader Academy sessions with CSCH staff, the decision to focus with school leaders on the topic of SEB well-being was intentional.

“SEB is a big worry and what we’re struggling with right now as to how to position schools to provide necessary supports,” says Chafouleas, who also serves a Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Educational Psychology at the Neag School.

“Education is a critical foundation to reducing each child’s net vulnerability, which drives long-term outcomes and intergenerational disparities,” she adds. “The things we do in schools can drive pathways to reducing these vulnerabilities, allowing schools to serve as assets.”

In a 2020 survey of school administrators across Connecticut, twice as many school administrators said that employee wellness had landed among their top three priorities during the pandemic, compared with before.

Physical and Emotional Safety

Over the course of two days in June, the SEB Leader Academy introduced participants to key issues and the latest research findings related to social, emotional, and behavioral well-being.

Among the findings CSCH shared were results from a 2020 survey of school administrators from across the state. Amid COVID-19, ensuring a safe environment in their schools emerged as a top worry for respondents. Survey participants also indicated that the pandemic had emphasized the need to address the wellness of their school employees. In fact, more than twice as many administrators said that employee wellness landed among their top three priorities during the pandemic, compared with before.

Academy facilitators also walked attendees through the holistic model known as the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC). Designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WSCC serves as a comprehensive and integrated framework for addressing health and well-being in schools.

Attendees discussed how WSCC could be used to enhance systems of support — by more effectively integrating efforts across academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and physical domains — and how they might then apply this knowledge in their own school settings.

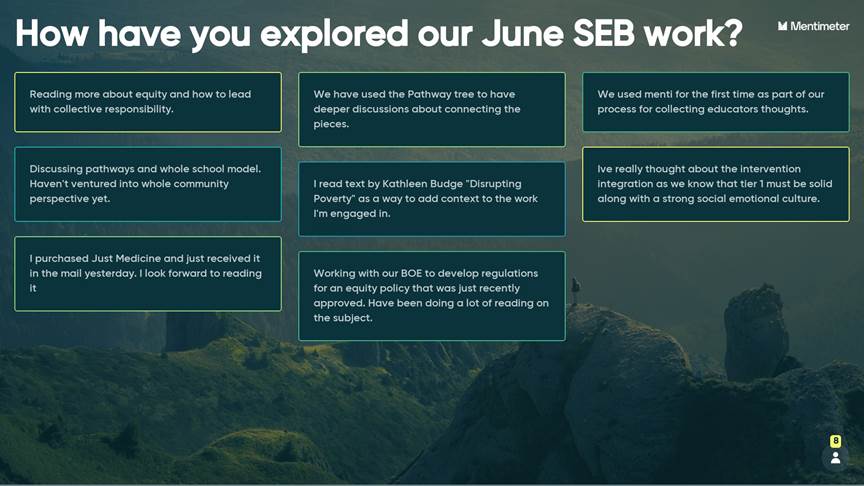

A follow-up session held this past week reunited the group for further interaction, including hearing how participants had so far begun to use what they had learned in the previous Academy sessions. For some, that included seeking out resources and literature on the concept of equity; others said they had initiated in-depth discussions on SEB within their districts or had worked toward developing an equity policy.

Chafouleas also spent part of the August session talking about common ways in which individuals of different age ranges may react to enduring trauma. For instance, while adults or adolescents may withdraw from social situations or increase their use of alcohol or drugs in order to cope, school-age children exposed to traumatic situations may show aggressive behavior or begin to perform poorly in school.

In a trauma-informed school, promoting SEB does not only encompass physical elements such as having a safe and secure building, Chafouleas says.

“Last year, there was so much focus – with good reason – on the physical space,” Chafouleas says, as schools took steps to ensure their spaces were properly disinfected and ventilated amid COVID-19. Yet fostering emotional safety for everyone in the building, she adds, is just as essential to a safe school environment. “Everyone needs to be a part of that – from the bus driver to the cafeteria worker to the hallway monitor to the teachers in the building.”

Simple Strategies for School Leaders

Chafouleas outlined simple strategies that school leaders can implement to promote emotional well-being in their students, staff, and themselves as the new school year begins. Each core strategy, known as a “kernel,” is cost-efficient, highly usable, and based on research. They can include anything from sending staff a virtual ‘praise’ postcard to making time to greet students and staff each morning as they enter the building.

Marjorie Coble, an assistant principal at Geraldine Johnson School in Bridgeport, Connecticut, says she, for one, hopes to implement kernels like virtual postcards, breathing strategies, and gratitude circles for school staff this coming school year.

Monthly check-in meetings will continue throughout the rest of the academic year so that Academy participants can maintain and further build their networks for sharing ideas with peers as well as efforts that prove successful in their districts and schools.

“The most valuable aspect about the SEB Academy is the opportunity to connect with other districts for the purposes of networking and learning more about the various approaches to supporting SEB across the state of Connecticut,” says Monica Abbott, the district social and emotional learning coordinator in New Haven, Connecticut. “Hearing from districts such as Stamford, Bridgeport, Vernon allows us to hear different perspectives on similar work. It will provide us future opportunities to share resources and best practices.”

“I am hopeful to network with fellow academy participants to collaborate and support each other through challenges and celebrations of success,” she adds.

“Hearing from districts such as Stamford, Bridgeport, Vernon allows us to hear different perspectives on similar work. It will provide us future opportunities to share resources and best practices.”

— Monica Abbott, district social and emotional learning coordinator, New Haven (Conn.) Public Schools

Partnering With Alliance School Districts

CEPARE’s mission centers in part on bringing together scholars and practitioners from diverse areas of expertise in education to work collaboratively in producing high-quality research, evaluation, and policy analysis related to all facets of education.

In seeking to transform the educational experiences and outcomes of traditionally underserved students, CEPARE has partnered with 33 school districts and the Connecticut State Department of Education to foster various collaborative learning, research, and engagement efforts.

Known as the Alliance for Socially and Educationally Transformative Engagement and Research (SETER), this particular partnership focuses on supporting students in Alliance School Districts. Alliance School Districts comprise 42% of the state’s school population, serving more than 200,000 students and upwards of 400 schools in urban, suburban, and rural settings.

Over the coming academic year, CEPARE will be holding additional events, including those designed for the SETER Alliance.

Visit CSCH’s website at csch.uconn.edu for more information and various COVID-19 resources for schools. To learn more about CEPARE, including the SETER Alliance and its other partnerships, go to cepare.uconn.edu.