In a summer when gun violence is on the rise in the United States and Connecticut, UConn sociology professor Mary Bernstein is examining the problem and looking to see what can be done to reverse the disturbing trend.

“I am really interested in how groups work together across lines of racial and geographic difference, how they define gun violence, and what they think the best strategies are for solving the problem,” says Bernstein.

In her 2019 paper, “Once in Parkland, A Year in Hartford, A Weekend in Chicago: Race and Resistance in the Gun Violence Prevention Movement” (co-authored with Jordan McMillan, a recent UConn sociology doctoral graduate and Elizabeth Charash ’18 (CLAS), a project manager at the Brady Campaign), Bernstein examines the extra work that racially oppressed people must do in their activism because the public views the gunshot deaths of Black and brown bodies in urban settings, which constitute the majority of deaths by gun violence after suicide, as routine, whereas gunshot deaths in suburban settings are seen as extraordinary and worthy of outrage

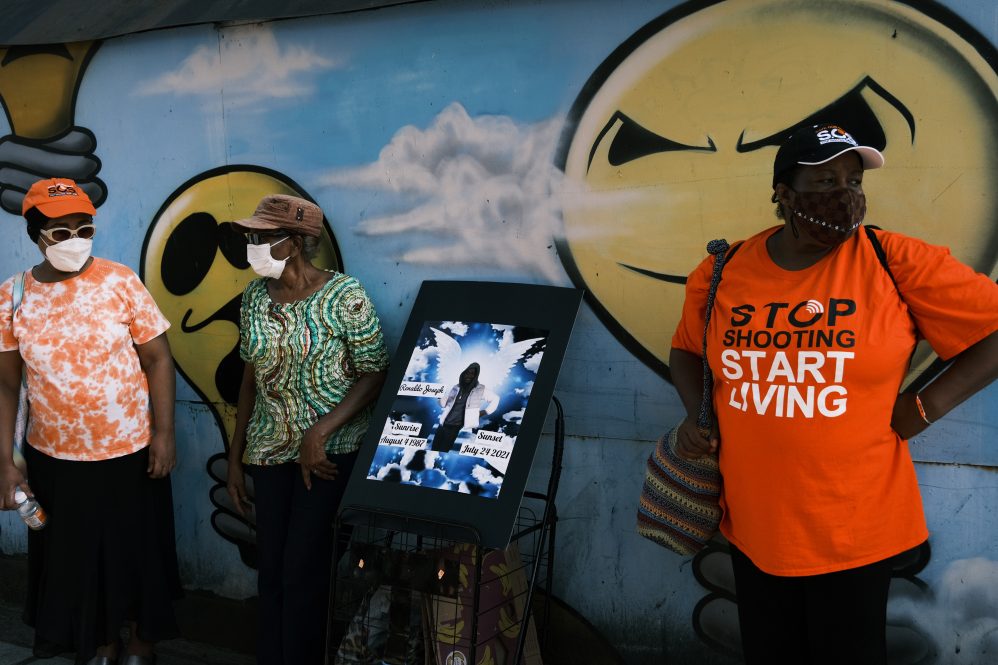

“In that paper, we also look at the different challenges that movements face,” says Bernstein. “Gun violence that takes place in urban areas and are a function of concentrated poverty, lack of good housing, lack of economic opportunities, which then results in high levels of community gun violence in certain neighborhoods and particularly high rates of death and injuries among Black and brown people, especially men.”

Bernstein pays close attention not only to why there is disparate attention given to different kinds of gun violence, but also to how activists contend with it.

“When you have a case like Sandy Hook, which was a terrible tragedy where 20 first and second graders and six educators were murdered in their school, the entire country mourns – as they should,” says Bernstein. “But in the same year you have roughly the same number of people killed in New Haven, Hartford, or Bridgeport, maybe a bit less, and yet nobody seems to pay attention, and why is that?

“That is where I come from – to really think not only why there is this disparate attention given to different kinds of gun violence, but how do activists contend with that?”

Bernstein examines these issues with Jordan McMillan in an article published this year entitled “Beyond Gun Control: Mapping Gun Violence Prevention Logics.”

“In that paper, we really map out what we call ‘gun violence prevention logic,’ and what we argue is, there are two particular logics,” says Bernstein. “There is the reform logic, and that’s what people typically think of as politics: Let’s try to change the laws and policies so people who shouldn’t have guns, don’t have guns, and that guns themselves are made less lethal.

“That logic is really important, but a second approach is what we call an intervention logic. That is really trying to tackle the root of gun violence in a different way, and it’s really about trying to interrupt violence at all different levels. This might take the form of street outreach workers or violence interrupters. The goal is to really prevent violence before it happens. This work takes places in hospitals too, where if someone has a gunshot injury, a staff member sits down with the family and friends and tries to make sure there is no retaliation and that the family has the support they need. It’s really about painstakingly trying to interrupt violence before it happens.”

In a separate research project, Bernstein worked with a team of other UConn faculty members and graduate students – including Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Psychological Sciences Blair T. Johnson and Kun Chen, associate professor of statistics – publishing a paper in the journal Social Science & Medicine entitled “Community-led factors and incidence of gun violence in the United States, 2014-2017.”

The paper concluded that “gun violence is higher in counties with both high median incomes and higher levels of poverty, characteristic of racial segregation and concentrated disadvantage, a legacy of institutional racism, negative police-community relations and related factors.”

As Bernstein reflects upon the issue, it can be very personal, like it is for most people.

“I think, like a lot of people, I hadn’t thought a lot about gun violence in Connecticut until Sandy Hook happened,” says Bernstein. “I remember hearing the news on my way to the airport to pick up my father and stepmother and thought, How is this happening? But again, part of this is also a function of, where do I live versus where is the community gun violence taking place? As a white woman, I don’t live in a gun violence hot spot area.

“I think that people have no idea how much gun violence takes place on an everyday basis. I think that people who are outside of those neighborhoods that are gun violence hot spots just don’t know. People living in the North End of Hartford live a very different reality than people who might live three or four miles away in West Hartford. One of the things I’ve learned in my research is that a lot of white people, a lot of white activists, have an ‘aha moment,’ when all of a sudden they realize that ‘wow, this is terrible.’ They know tragic mass shootings happen, but had no idea this was going on regularly in these urban areas that are just down the road.”