Cornelia Dayton, a professor of history at UConn, has helped uncover some missing pieces in the life story of Phillis Wheatley, author of the first volume of poetry published by an African American.

In a prize-winning research paper recently published in the New England Quarterly, Dayton describes her findings on the later parts of Wheatley’s life. Born in West Africa, she was ensnared as a child in the transatlantic slave trade. Arriving on a slave ship in Boston in 1761, she was purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, a wealthy merchant couple in Boston.

“The Wheatleys realized her gifts at learning and so she studied English, Latin, and classical literature; she started writing poems as a teenager,” says Dayton.

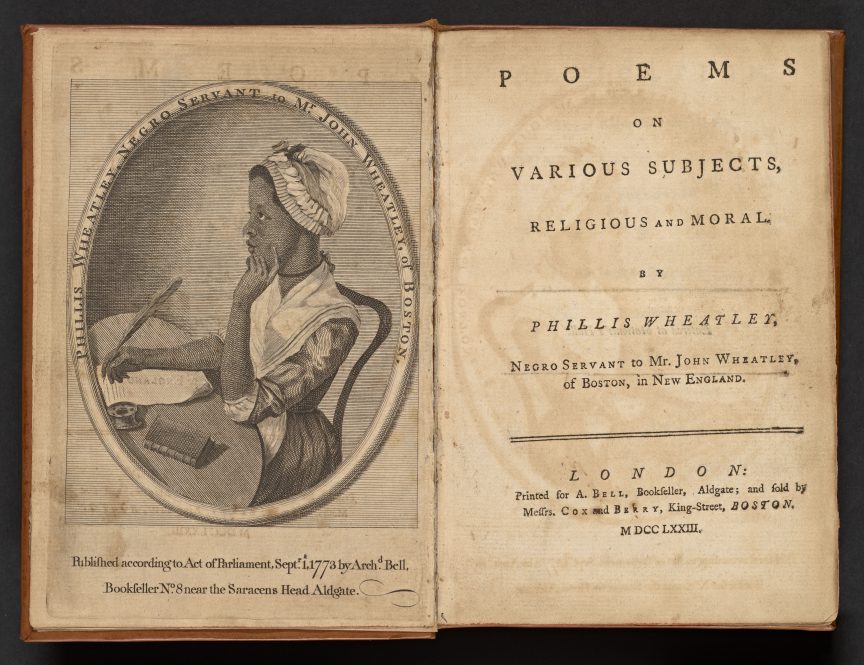

Wheatley visited London in 1773 with the wealthy couple’s son, and found a publisher for “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” the first book of poetry by a Black American. On her return to Boston, she and her London allies successfully pressured the Wheatleys to free her from slavery. “Today, she is anthologized, taught, and lauded as an important early African American writer and figure. The news of my research is that there is now extensive knowledge about three years of her later life, which have been lost and missing.”

In 1778, Wheatley married John Peters, a freed Black man about whom very little was known before Dayton’s research. The couple left Boston about a year later and were gone from the area for three years. In late 1784 Wheatley died in Boston, in her young thirties, perhaps from an illness such as tuberculosis or pneumonia.

Although Dayton is not a scholar on Wheatley specifically, one of her specialties is legal history. She found the story too good to pass up when she stumbled upon legal papers from the 18th century that contained previously unstudied records about Wheatley’s husband.

“I was able to establish where they went for those three years and much about John Peters – we never knew anything about his backstory,” says Dayton. “He had been enslaved in an obscure town in Essex County– Middleton, Mass. In an unusual move, when he became a free man he befriended his former enslavers. We don’t know exactly how he got his freedom. We know he had been sold by his initial enslavers, Lieutenant John Wilkins and his wife, Naomi.

“As an adult, he comes back to the Boston area and convinces his former enslavers that, because they do not have a son, he is the most trustworthy person to help them in their old age and take care of their estate.”

After John Wilkins died, Naomi Wilkins asked Peters to move into the household and run the farm in Middleton, an impoverished, interior town north of Boston, near Andover. She even deeded him 110 acres, another unusual move for the time. But the deed was conditional: in return for the acreage, Peters agreed to support the widow comfortably for the rest of her life.

“The story gets harrowing, because eventually his relationship with the widow has a rupture,” says Dayton. “The widow moves off the farm to a rented house and orchestrates over half the white male household heads to sign petitions opposing Peters’ management of the Wilkins estate. Eventually, she is able to get him off the farm through an ejectment suit.”

And what about Phillis Wheatley Peters, celebrated in the newspapers as an accomplished poet, during this span of years?

“The litigation barely mentions her and never by name,” says Dayton. “The 120 or so legal papers tell us a lot about her husband, which is useful, but we have to infer how she reacted to and coped with the increasingly hostile situation that the couple faced in Middleton. We don’t know what her relationship was with the neighbors. The documents do tell us, for the first time, that John and Phillis Peters had at least one infant living in these years. However, even with considerable documentation, there is much we don’t know, but people tell me these findings are going to be of considerable interest to scholars in the field and public historians.”

Dayton’s research is also important because it helps debunk the myth that it is impossible to research and trace people of African descent in the United States prior to the end of slavery.

“Genealogists, local activists, and academics are finding out there is quite a lot of information about individual people of color in the archives in every state, not just in New England,” says Dayton. “We are justifiably frustrated that white people in power tended not to record Black people’s stories or even names. But, fortunately, there are exceptions, and researchers have trained themselves to read against the grain. There are ways to follow up on small details, as we can do using the many legal papers filed in the cases involving John Peters.”

Dayton is part of a cohort of scholars in UConn’s History Department that is researching, writing, and documenting the experiences and lives of Black people, including professors Manisha Sinha, Jeffrey Ogbar, and Micki McElya, associate professors Ricardo Salazar-Rey, Fiona Vernal and Melina Pappademos, and assistant professors Dexter Gabriel and Melanie Newport.

“The stories of prominent Black people in the 18th century are few and far between, and it’s exciting when we find out new information about figures that we are already familiar with and we can add a little bit more texture and details to understanding their daily lives,” says Vernal. “Dayton has skillfully teased out a powerful and insightful story about the limits and possibilities of freedom and citizenship from legal documents whose purposes were not to reveal much of anything about Black lives.”

Dayton is working on developing a pilot website for The Wheatley Peters Project, in hopes of it going live in early October. Developments related to the website and public programming on the new findings can be found on Twitter @Wheatley_Peters.