In May 2021, Dwayne Proctor ’92 (CLAS), ’95 MA, ’99 Ph.D. started as the CEO and President of the Missouri Foundation for Health, an independent philanthropic foundation committed to eliminating the underlying causes of health inequalities. He previously worked at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for 20 years, where he led public health projects ranging from child obesity to COVID-19 disparities. Proctor is also on the front in the battle for racial equity in the U.S., serving on the NAACP Board of Directors for 13 years and counting. He explains how his time on tour with legendary musician Ray Charles led him to UConn and a distinguished career.

You started your undergraduate career at Virginia Tech. What made you transfer to UConn?

UConn had a really good name in the state. I was new to Connecticut, working as a cook in Cromwell, and the reputation of the school was strong. I transferred after a period when I was out of school for five years. I wanted to finish my degree and start my career in radio. That’s where I really wanted to be. The school I attended before, we learned vocational skills for media jobs. When I came to UConn, I had to learn to use statistics and theories to help understand how media and communications may influence or impact life. I came to UConn to get a communications degree and got more than that. It set me on a path to public health.

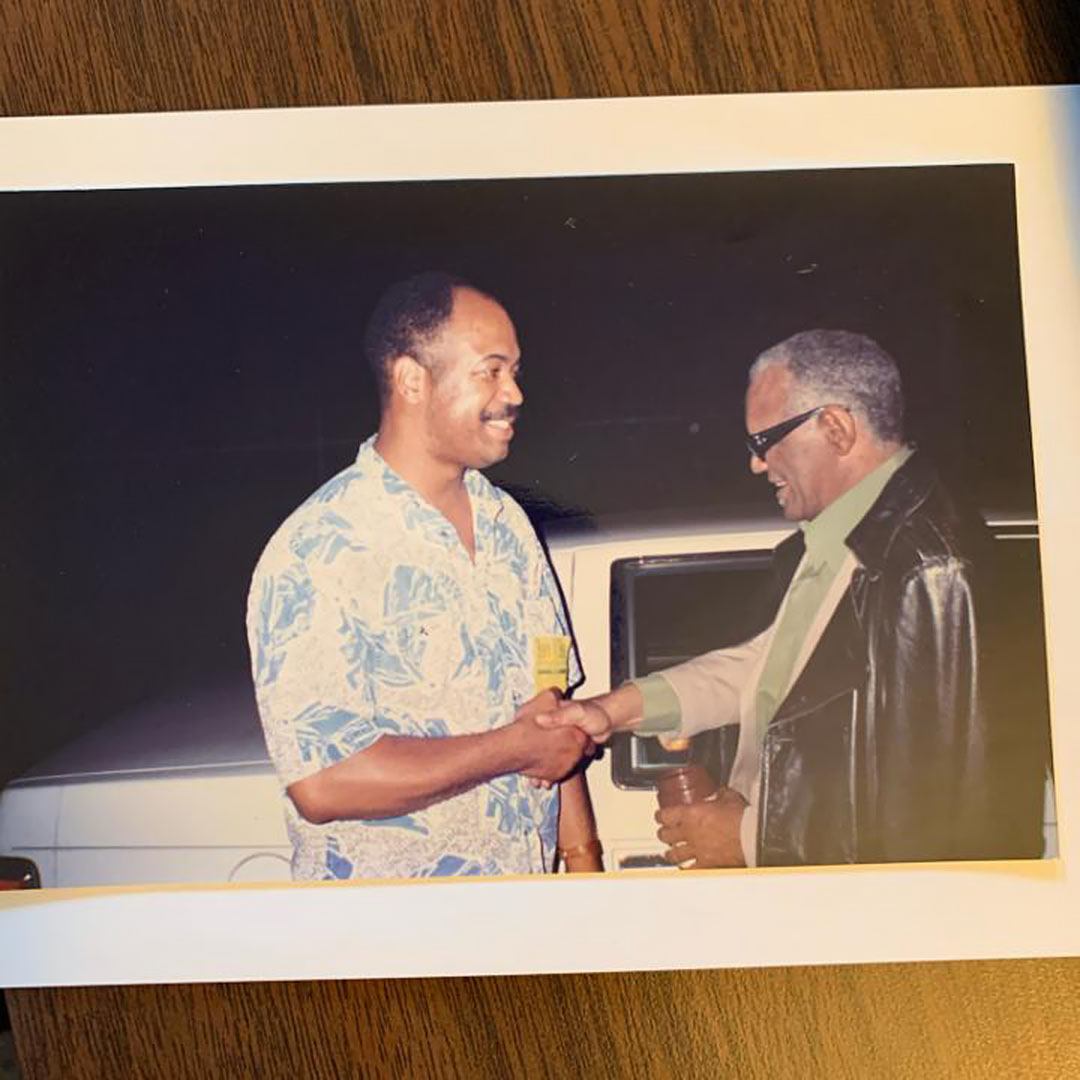

You worked on world tours with Ray Charles between your time at Virginia Tech and UConn. What was that experience like?

It was a great experience. I got to travel around the world with world-class musicians. I got to meet different people and see different cultures. At that time, my goal was to be in communications as a DJ or music producer. I learned so much – [Ray is] a genius. He found a way to navigate the world with a disability, but I never saw it that way.

I wouldn’t have landed in Connecticut if it wasn’t for him. One night, Mr. C and I were talking and he said, “You should go back to school. This wasn’t supposed to be your career path.” And I did. I left Los Angeles and came to Connecticut.

Is there a UConn professor that had a positive impact on you?

When I was an undergrad, this was the same time as the Rodney King trial through the OJ Simpson case. During that time period, to be outspoken was one thing, and I was outspoken. There are other times where diplomacy was the best tool in trying to explain my experiences and the experiences of other African Americans on campus.

There were a lot of people commenting on my outspokenness. Professor Noël Cazenave, he was outspoken as a professor. Professor Leslie Snyder, who was my major advisor, I give her the credit for the diplomacy side. She understood the risk I was taking. Risk like this: If I was no longer welcomed at UConn, where would I go? What am I supposed to do with my life? Sometimes you really have to think before you say what you say. So I’ll give her credit for that, and I’ll give Noel the credit for the passion and the courage to say things folks didn’t want to hear.

How did you get involved in public health after earning your Ph.D.?

I had good experiences teaching as a graduate student. I had taken a few public health courses, and I had the opportunity to adjunct at the UConn Health Center. It was a different environment, very medicine and healthcare-oriented. I was transitioning into the role nicely, working on interesting projects with fantastic people around alcohol use and community health. There was a project I did called Cutting Back, a national program to reduce alcohol use disorders in adults. It was through that project that the UConn Health Center introduced me to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. During that period, I got a call from the Foundation saying that they had a position that was right for me, and they invited me to interview.

You worked at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for almost 20 years. Talk about your personal and professional growth during that time.

The Foundation was very similar to being at a university. It’s a place where all of your colleagues are your professors, and you can be their professor. The commitment to the mission – improving health and healthcare for all Americans – was what brought us together. It was like being in a think-and-do tank, because you could work with some great experts from around the country, think of problems the country was dealing with, and find solutions.

Around my third year, I was asked to lead the childhood obesity prevention work at the Foundation. I used what I learned at UConn to start thinking about national strategies for reversing childhood obesity trends during that time period. Even though the focus was childhood obesity prevention, we learned a lot about tobacco control and alcohol use – all the bad things folks get into that make them unhealthy.

How did COVID-19 impact your role?

When COVID started, it became an all-hands-on-deck phenomenon. One project I assumed early in the pandemic drew attention to the fact that demographic data was not collected at testing centers. Our small, targeted campaign forced the Center for Disease Control and Prevention to report demographic data to Congress on a regular basis. One project in the first month of the pandemic led to changes in the way we now look at COVID prevention and treatment around the country. Two months later was the murder of George Floyd. Once again, all hands were on deck trying to figure out what our role was going forward on issues of racial equity.

I came to UConn to get a communications degree and got more than that. It set me on a path to public health.

You recently took over as President and CEO of the Missouri Foundation for Health. What made you take the position?

The Foundation and its location are primed for equity. I’m only six miles away from Ferguson, one of the flash points for the Black Lives Matter movement. You have a lot of progressive leaders and many conservative leaders in the state. Missouri was ahead of other places in starting to deal with the racial reckoning before the murder of George Floyd. Being here feels right, it feels good, and it’s complex. There are things from an East Coast perspective that we might not understand about Midwestern life. I’ve read stuff, but once you see it and live it, you appreciate it more.

You’re also chair of the Board of Trustees for the NAACP Foundation. What motivated you to join such an important organization?

Both of my grandfathers were civil rights leaders in their communities. My mom’s dad was a Baptist preacher in West Virginia and my dad’s dad was a Pullman porter in Washington, D.C. They were the architects for the civil rights movement.

If you’re going to work for progressive change, you probably shouldn’t do it alone, so you connect with an organization like the NAACP. I’ve served on its Board of Directors for 13 years. My community service has a global and national impact. I’m just carrying on the legacy of my ancestors, grandparents, and those before them. Just keep in mind that the struggle continues and doesn’t have an expiration date.

What goals do you still want to achieve in your career?

It has to do with this concept of equity. Equity is not equality. Equity means making sure all of us have a fair opportunity to thrive. We have to admit the systems that control our lives discriminate against people, and we have to eliminate the discrimination from the systems. I want to make the case here in Missouri. I want to prove it, because if you can do it here you can do it anywhere.