Archaeologists have documented the earliest evidence for tending food animals in the world, dating to roughly 12,500 years ago, at a site call Abu Hureyra in Syria, using remnants of ancient animal feces. The research was published this week in PLOS ONE.

For millions of years humans obtained food solely by hunting and gathering wild plants and animals, until just over 10,000 years ago, when they began experimenting with food production. The process of domesticating animals would have included a range of management strategies that shifted in intensity over time. People are likely to have begun by tending a few wild animals on-site, possibly for short periods of time to fill gaps in the hunting cycle. Later on, as the level of oversight intensified, people eventually took control of the reproductive cycles of large herds that needed year-round care. Observing the beginnings of this important transition using archaeological evidence can be complicated.

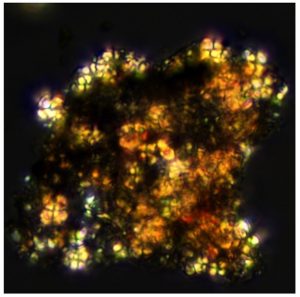

(Photo credit: Alexia Smith).

Traditionally, archaeologists have examined changes in the shapes of animal bone that vary between wild and domesticated animal populations. While this approach provides an enormous amount of information, changes to bone shape occur well after the process of tending and domestication began, leaving the earliest experiments with animal management hard to track.

There is another method that allows archaeologists to look further back in time using microscopic, calcium-based balls that form in the intestines of many herbivores called dung spherulites. When live animals are kept on-site, they create accumulations of dung. Observations of dung spherulites allow archaeologists to examine the period before full domestication occurred, to determine when people first began bringing live animals to sites and caring for them. This type of caring can range from casual to intensive.

Until recently, it has been hard to find a method that would allow archaeologists to examine the very earliest experiments with animal tending prior to fully-fledged animal domestication and herding, so it is really exciting to see that remnants of animal dung can help us track the differing ways that people interacted with animals early on. We were surprised when we realized that hunter-gatherers were bringing live animals to Abu Hureyra between 12,800 and 12,300 years ago and keeping them outside of their hut. This is almost 2000 years earlier than what we have seen elsewhere, although it is in line with what we might expect for the Euphrates Valley.

First excavated in the 1970s by a team led by Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the Rochester Institute of Technology Andrew Moore, Abu Hureyra continues to be an important site to help understand where and when agriculture was first developed. The site now lies submerged under Lake Assad following the closure of a dam, close to the modern-day city of Raqqa in northern Syria within an area known as the Fertile Crescent.

Different layers of habitation at Abu Hureyra have been built on top of one another for over 5,550 years. The oldest layers include a small settlement created by hunter-gatherers that was first settled at the very end of the Paleolithic or Stone Age, dating to 13,300–11,400 years ago, during a time period known as the Epipalaeolithic. Later, a series of villages were built above the early settlement by farming and herding communities during the Neolithic period (10,600–7,800 years ago). Together the different layers of occupation, along with studies of ancient seeds, animal bone, architecture, and tools provide detailed information on the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture.

Researcher and co-author from Durham University, Peter Rowley-Conwy, studied the animal bones from Abu Hureyra. Remnants of animal bone show that during the Epipalaeolithic period, hunter-gatherers began to increasingly rely on sheep to supplement a diet based mostly on hunted gazelle, although they also caught small game such as birds, hare, and fox.

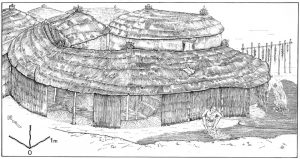

Eventually, by the Neolithic period, herded sheep and goat became more important than hunted animals, and the huts were replaced with mudbrick houses. These trends, combined with observations of accumulations of dung immediately outside of a hut at Abu Hureyra dating between 12,800 and 12,300 years ago, indicate that hunter-gatherers were bringing small numbers of live animals, most likely sheep, to the site and holding them there.

(Image credit: Andrew Moore).

This finding is the earliest evidence for the co-presence of people and animals that would later become domesticated, marking the beginning stages of a revolutionary transition away from hunting and gathering to fully-fledged farming and herding.

Archaeologists have to be very creative in figuring out how people lived in the past. As hunter-gatherers began to experiment, bringing live animals to the site—even if it was for a short period of time—they would have had no idea of the massive societal changes they were setting in motion. The way we live today rests heavily on this shift from a reliance on hunting and gathering wild plants and animals to a dependence on growing and herding our food.

Once agriculture was established, it quickly became the main strategy for obtaining food and laid the foundations for the development of large villages, the development of specialized trades and, later, the emergence of writing, cities, and enormous social inequalities.

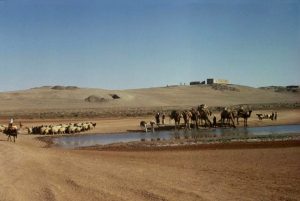

(Photo credit: Andrew Moore).

The shift was truly revolutionary and forever changed the ways we interact with the natural world and with each other. We would not be living the lives we do today if this change had not occurred.

Co-author Moore says this research represents a major advance in our understanding of the critical early stages of animal management leading to full domestication.

Samples excavated at Abu Hureyra during the 1970s are still very informative. For this study, dust was examined from “flotation samples” that are currently curated within the Institute of Archaeology at University College London. The flotation samples had initially been gathered to examine organic materials such as seeds and wood, but this study demonstrates that they contain a range of additional clues to the past, including dung spherulites. We were able to study the samples in the Archaeobotany Laboratory at UConn with the help of co-author Amy Oechsner, a graduate student from Tübingen University, who was visiting UConn as part of the Universität Tübingen-University of Connecticut (TÜConn) graduate student exchange funded by UConn’s Office of the Provost and the Office of Global Affairs.

Not many researchers have used fecal markers to track the presence of animals on sites occupied by hunters and gatherers, so it is likely that future work examining palaeo-feces will continue to provide new insights about this important transition in our collective human past.