When Kat Milligan-McClellan arrived at UConn in fall 2020, she looked around at the rolling hills, the autumn leaves, and the 18th-century buildings, and immediately knew: Something was missing.

“There were as many as four monuments to Nathan Hale in my town,” says the assistant professor of molecular and cell biology and member of the Inupiaq people. “But there was nothing about Native Americans – no markers, no monuments, no acknowledgments. Nothing.”

And UConn was no different.

“We were struck by the level of Indigenous erasure on campus,” says Sandy Grande, professor of political science, director of the new Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative and a Quechua national. “You’re hard-pressed to find anything on campus that speaks to the continued presence of Indigenous peoples.”

Yet, what Grande and Milligan-McClellan did find was a committed group of students hard at work building a UConn Native American community: inviting and hosting prominent Native American speakers, creating Native American student organizations and academic communities, and supporting a mentoring program for Indigenous youth.

“Student involvement has driven UConn’s efforts to reclaim an Indigenous presence on campus,” says Grande. “And together in intergenerational partnership, we now have potential to do so much more.”

Native student power

In 2021, only 40 of the more than 32,000 UConn students identified as Native American or Indigenous. Grande and her colleagues know of only six Native American faculty.

It wasn’t surprising, then, that in her speech at the 2022 Commencement Ceremonies, student speaker Sage Phillips ’22 (CLAS), a member of the Penobscot Nation, said that when she was applying to colleges, “it was clear rather quickly that UConn did not meet my list of conditions.

“I did not see a strong Native and Indigenous Studies Department, nor a large community of support for Indigenous students,” she said in her speech.

It was her father who counseled her to embrace the opportunity to build an Indigenous community at an institution that needed one.

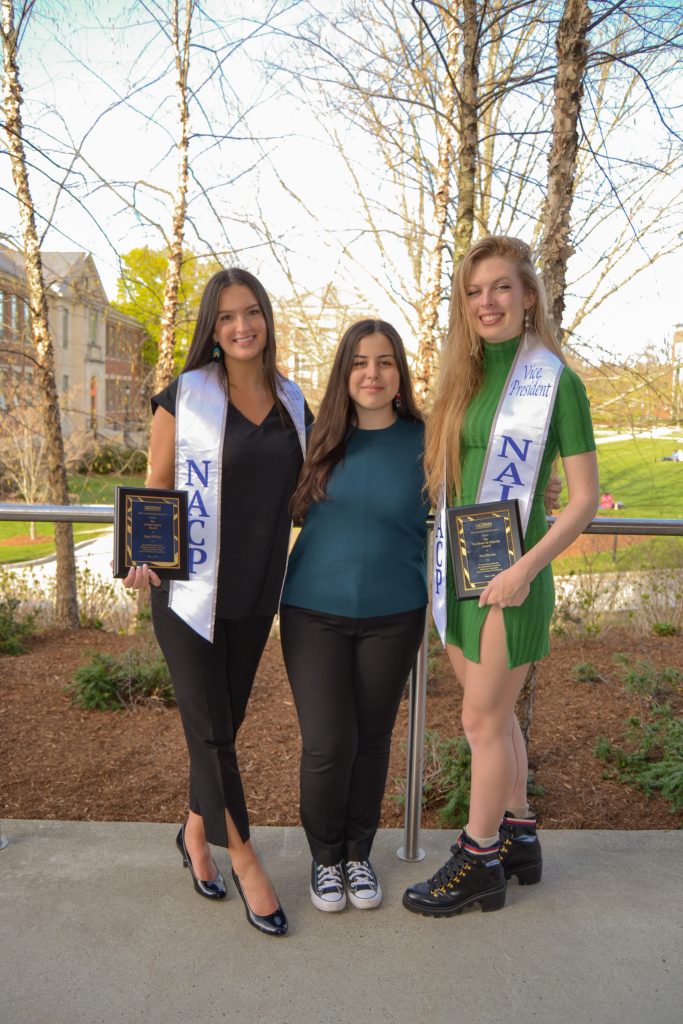

Leading a small but dedicated group of Native American students, Phillips came to UConn in 2018 and founded the UConn Native American and Indigenous Students Association (NAISA), in partnership with UConn’s Native American Cultural Programs (NACP). Fellow student Zoe Blevins ‘22 (CLAS), a human rights major, founded the UConn Indigenous Nations Cultural and Educational Exchange mentorship program (UCINCEE), which pairs Indigenous youth with undergraduate students from NAISA or NACP with the goal of fostering relations between Indigenous cultures and UConn.

The students also rejuvenated the UConn chapter of the Society for Advancing Native Americans and Chicanos in Sciences (SACNAS) and hosted prominent Native American speakers on campus.

By late 2019, Native and Indigenous programming had risen to an unprecedented level.

Then in 2020, Grande, Milligan-McClellan and Assistant Professor of Anthropology Nate Acebo came to UConn as part of a planned cluster hire to bring diverse scholars and perspectives to UConn.

The professors formed the Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative (NAISI), which serves as an academic home for the NAIS minor and associated courses and programming to strengthen the Native American and Indigenous community at UConn and beyond.

Milligan-McClellan immediately recognized the sheer amount of effort and care the student community had devoted to their cause. She and her faculty colleagues cites the students as a reason they chose UConn.

“The students were the ones who really got us all together,” says Milligan-McClellan. “It’s amazing to have such a strong student community.”

“Having dedicated the entirety of my undergraduate career to expanding our resources and community on campus, it felt as though we had done something right when Sandy, Kat, and the rest of the NAISI team came to UConn,” Phillips says. “They saw our potential and trusted us and our efforts.”

With the addition of Assistant Professor of History Hana Maruyama and Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership Chen Chen, UConn’s first critical mass of scholars focused on the study of Indigeneity and settler colonialism was created.

A history erased

The culture and history of Native tribes in the Northeast is unique, says Grande. Northern peoples like the Mohegan, Pequot, and Nipmuc tribes have deeply overlapping histories. Prior to colonization, some tribes were once the same peoples, and those familial ties persist to this day.

What’s more, a fascination with New England colonial history has contributed to the lack of Indigenous knowledge and culture, Grande says.

“New England has a history of Native erasure,” says Grande, who grew up in Hartford. “Children do not learn Native histories. We need to change that.”

In collaboration with Glenn Mitoma, then-Director of Dodd Human Rights Impact, Phillips has worked toward this change through the research project Land Grab Connecticut. Inspired by the national Land Grab U and produced through UConn’s Greenhouse Studios, the project maps land data tied to Connecticut public universities, including UConn, to show how they are intertwined with colonialism, says Grande.

And that’s just one step in the right direction. The NAISI faculty see UConn as uniquely positioned to become a center for Indigenous study and community in the Eastern U.S.

With colleagues at other northeastern universities such as Quinnipiac, Eastern Connecticut State University, Yale, Dartmouth, Columbia, and Brown, the faculty plan to build what they’re calling the Quinnehtukqut River Collective – named for the Algonquin word giving rise to “Connecticut” – to raise the visibility and significance of Native peoples and culture in the Northeast.

UConn’s central location and its history as a land-grant university makes it an ideal hub, Milligan-McClellan says.

“One of the tenets of being Inupiaq, and of being Native American, is community,” she explains. “It was drilled in from a very early age: what you do, you do with and for your community.”

‘IndigaPalooza!’

The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Dean Juli Wade and Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Kate Capshaw have worked hard to bring Grande and her colleagues to UConn, and have been supportive of NAISI from the start, Grande says.

“The College brought in five new Native studies faculty pretty much at once – that’s just unheard-of,” says Milligan-McClellan. “I thought, I want to be at the ground floor. I want to be able to shape the direction of this Indigenous community at UConn. That’s what drew me here.”

With support from UConn’s President’s Commitment to Community initiative, NAISI developed and presented a seminar series with panel discussions and external speakers throughout 2021-2022.

The event, colloquially known to organizers and attendees as “IndigiPalooza,” was co-sponsored by the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program and their director, Associate Professor-in-Residence Sherry Zane, along with Associate Professor of English Bhakti Shringapure and her program, the Radical Books Collective.

The program culminated in a two-day conference in April 2022. which was the biggest Native American gathering in UConn’s history, says Grande.

More than 100 students, faculty and community members from around New England attended standing-room-only events to learn about teaching, research and advocacy for Native American issues.

IndigiPalooza featured discussions on Indigenous women in STEM, presented by Milligan-McClellan; Indigeneity as represented in multimedia, presented by Acebo; and the history of Black and Indigenous schooling and pedagogy, presented by Grande.

It also featured a workshop on integrating decolonial methods and centering Indigenous histories in teaching, and two film screenings: the Emmy-nominated “End of the Line: Women of Standing Rock” about the Dakota pipeline access controversy, complete with visiting members of the cast; and “Beans,” a story about a young Mohawk girl coming of age during the Oka Crisis, an Indigenous uprising in Canada in the 1990’s.

The series was promoted and bolstered by NACP, which has long sponsored UConn programs for Indigenous People’s Week and Native and Indigenous Heritage Month, including an annual Rising Sun Powwow in Gampel Pavilion.

The professors credit the Native American and Indigenous Student Association, the group begun by Phillips, as a major precursor to the symposium.

Native Studies at UConn

This fall, 40 Native American students were admitted to UConn, which doubles their representation on campus.

But, since so few students realize that they can study and earn a minor in Native American and Indigenous Studies, the faculty are developing a general-education class to bring the topic to students in their first years in college.

Several new undergraduate courses began last year: Milligan-McClellan taught about historically excluded and underrepresented scientists, which drew from her years of Native activism and knowledge of Black and Indigenous movements on college campuses. Grande taught a class on Native American theory and politics, and is developing a course on Indigenous Elders, aging and politics.

Outside the classroom, Grande, Milligan-McClellan, Acebo and their peers spend time mentoring Native American undergraduates and educating the broader community. There are so few Native American faculty, Grande says, that their labor is in high demand. She loves working to build Native Studies at UConn, but she looks forward to sharing the job with more Native faculty in future years.

Current NAISA president Samantha Gove ’24 (CLAS), a sociology and human rights major, also hopes to see more Indigenous faculty in future years.

“As a Mashantucket Pequot high school student, I never saw myself going to UConn,” she admits. “Ten years from now, I hope to see UConn become a university that our local Indigenous youth would be excited to attend because of their Native and Indigenous institutional support and programming, not in spite of their lack of it.”

“UConn as a land-grant institution has a responsibility to our community, our families, and our ancestors and that responsibility is uplifting our needs and hearing our voices,” adds Phillips.

Unfolding Futures

With momentum continuing to build, the NAISI faculty are building relations between UConn and the five recognized Native tribes in Connecticut: the Mohegan, the Mashantucket Pequot, the Schaghticoke, the Golden Hill Paugussett, and the Eastern Pequot. They’re made contact with key leaders, including Chief Mutáwi Mutáhash (‘Many Hearts’) Lynn Malerba ’08 MPA of the Mohegan tribe, who was recently named the first Native American U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

The NAISI faculty are working toward more physical campus space and creating a greater presence of Native and Indigenous peoples and communities on campus. The recent hire of Visiting Instructor Chris Newell of the Passamaquoddy tribe, one of the founders of the locally-based Akomawt Educational Initiative, and his expertise on approaches to Native American and Indigenous education will go a long way toward creating this presence, says Grande.

In partnership with NAISA and Native students, they’re also advocating for commemoration of Indigenous peoples on campus. This isn’t just a gesture, says Milligan-McClellan – it’s among the best ways to make Native students feel welcomed when they first set foot on campus.

It will take many years to accomplish, but their work is just starting – and Milligan-McClellan says it doesn’t have an end.

“All of it is service, but we just think of it as living our lives,” she says. “It’s all community-building, and that’s what we do.”

“Some institutions want scholars who happen to be Indigenous. And other institutions make room for Indigenous scholars,” adds Grande. “The way we do work is different, and UConn is beginning to understand that.”