“Asian American Feminist Antibodies: Care in the Time of the Coronavirus” sounds like something that might never make its way to a university library. “Beginner’s Guide to Necromancy” may only seem fit for a magic shop. UConn’s Homer Babbidge Library, however, not only houses a circulating collection of these and many other small, creator-produced booklets known as zines, but also provides students the resources to create and submit their own for inclusion on the shelf.

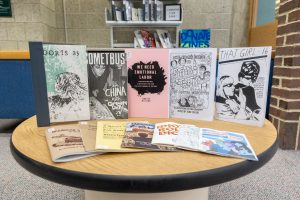

Since it opened in September, the Liberated Zine Zone in the library’s Leisure Reading Room on Level B has grown to about 100 zines. The authors of these publications include zine makers from across the United States, many from Connecticut, and several from the UConn community.

“Zines can basically be about anything, and they have many formats, so we wanted to get a good arrangement and a good sample of all of them,” says Metadata Management Librarian Rhonda Kauffman ’03 (CLAS) who uses she/they pronouns and catalogs and curates the library’s zine collection.

But what exactly is a zine? According to “Wicked Meta: A Zine About Zines no. 2,” a zine Kauffman made and contributed to the library’s collection, “[z]ines (rhymes with ‘beans’) are low-barrier, low-budget photocopied publications in which authors are in full control of the entire process of creating a publication, from writing and layout to printing and distribution.”

Since authors have control from start to finish, zines have often allowed people, especially those in underrepresented and marginalized movements and groups, to share their uncensored thoughts and experiences.

“There’s this element of being able to be anonymous if you wanted to, but also be very explicit, or be very much informative about your own experiences, and that’s not something that has typically been available to the majority of people for a very long time,” says Graham Stinnett, an archivist who works at UConn Archives & Special Collections, overseeing the library’s human rights and alternative press collections.

Kauffman and Stinnett sought and gained approval for the “Liberated Zine Zone” as a project to further the UConn Library’s Strategic Framework, which has three main goals: to connect, empower, and engage the UConn community at the library.

Stinnett notes that the zine zone takes inspiration from the work of another UConn archivist, Richard Akeroyd, who wrote in the 1970-71 Special Collections Annual Report about his desire to establish a “library liberated zone.” From Akeroyd’s efforts, Stinnett says he and Kauffman got the idea for “creating a space that was somewhat autonomous within the library that had some nontraditional, academic, but also personal creations.”

UConn Archives & Special Collections at the Dodd Center for Human Rights has unique and older copies of zines. The archives staff welcomes classes to schedule a visit to engage with these zines, but access to them is ultimately limited. At the “Liberated Zine Zone,” however, Kauffman emphasizes the zines are “just like any other book on the shelf.”

“This is a legitimate resource and thing that you can check out from the library and bring it back. You can treat it like any other resource there,” says Kauffman.

While some may be skeptical about using zines for research, Kauffman notes that they are great primary source materials that often relay “a firsthand account of somebody’s lived experiences or opinions.” In addition to the physical copies on level B, all of the zines are also available online on the library’s website and WorldCat.

“I put the record in WorldCat so then other libraries can have it, and then I create the authority record with the Library of Congress. It even further legitimizes this person as an author,” Kauffman notes.

Some authors of the collection’s zines are UConn students. In a book arts class last semester, studio art major Tomaso Scotti ’24 (SFA) saw zines at UConn Archives & Special Collections and used their portable zine-making kit to create a mini zine for a project. His publication, titled “The Astrological Guide to Your Local Libra” is now in the library’s collection and archives, which he says “was probably the coolest part.”

“I remember growing up, my cousin went to Pratt, and she was an architectural student, and I remember hearing about her work getting added to Pratt archives, and I was like, ‘that’s cool.’ And then having this opportunity at UConn to be a part of this archive, I feel really lucky,” Scotti says.

While zines can be made digitally, Scotti also emphasizes the appeal of taking time away from screens to create and read them.

“It’s an easy way to compile information together, and then print it and share it with people because websites and social media pages are great and all, but there’s nothing like getting your hands on a fresh zine. Nothing compares to it,” says Scotti.

To help students manually create their own zines, the Liberated Zine Zone collaborates with the UConn Library Maker Studio, which has zine-making kits that students, faculty, clubs, and others can check out for use. Once students make a zine, they can drop a copy in the zine zone’s donation box, or submit digital copies electronically for inclusion in the collection.

“The fact that you could possibly contribute something like this to a library and have it get cataloged in an academic library is very unique as far as its representation,” Stinnett explains.

Kauffman and Stinnett are excited to empower students with this initiative and to see the zines people contribute. Ultimately, Kauffman wants to slowly build the Liberated Zine Zone and make it a community collection.

“I hope to plant the seeds and encourage folks to help kind of curate it too and make it better,” says Kauffman.