Fiona Vernal wants her students to talk.

Talk to their parents.

Talk to their grandparents.

Talk to those in their communities who are shaping history right now.

“My students always wish they had spoken to their grandfather, who was a veteran,” says Vernal, an associate professor of history. “Or they wish they would have asked their parents, ‘What brought grandpa over from Italy? Or from Peru? Or from Jamaica?’ There’s this deep regret.”

Many of those intergenerational conversations never happen — and firsthand experiences get lost. Coupled with the lack of this history in textbooks and the classroom, racial and ethnic minority students are often unaware of contributions that their ancestors have made to society, economy, and culture.

But that’s slowly starting to change.

With the help of student advocacy and other nonprofit groups, Connecticut’s K-12 curricula are moving towards a more inclusive presentation and interpretation of history. And the state is turning to professors at its flagship university to help guide the process.

“There’s a crucial role for subject matter experts to play in curriculum,” says Vernal. “And that’s where CLAS faculty come in.”

Black and Latino History

In 2020, Connecticut became the first state in the nation to require all high schools to offer a course on Black, Puerto Rican, and Latino studies. It came after persistence and testimony from groups like Students for Educational Justice and Hearing Youth Voices.

“There were a lot of young people saying: we want to see ourselves in the curriculum. How come we don’t?” says Anne Gebelein, associate director and associate professor in residence in El Instituto.

There’s a crucial role for subject matter experts to play in curriculum.

Vernal and Gebelein saw a need for diverse content too. After seeing success in a pilot program, they are now collaborating with the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at the MacMillan Center at Yale University on a $30,000 Connecticut Humanities grant. The award supports the Black and Latino History Project (BLHP), a series of working groups for teachers to study and develop curriculum and resources on Black and Latino history.

Teachers in the program are supported in developing collective units on three themes: shade tobacco, migration, and eugenics — three understudied areas in the state and nation. During each module, they work closely with a historian familiar with the subject and explore places and people connected to each of these histories.

“We can help build off of topics that teachers know how to teach — such as labor, migration, and social justice — with content that they may not have gotten in college or grad school,” says Gebelein. “A lot of creative, smart teachers in the state really do want to get this right.”

Gebelein leads the workshop about agricultural labor in the state’s shade tobacco industry. The fall course includes trips to Jarmoc Farms in Enfield and the Connecticut Valley Tobacco Museum in Windsor.

“We are focusing on [Black and Latino] perspectives and their positionality in history,” Gebelein explains. “How they saw history, how they see their contributions in history, which may be different than how these histories and dynamics have been taught in the past.”

Vernal, who serves as academic advisor on the project, says teachers can always plan for new material, but when it comes to implementing it in the classroom, proper training is key.

“We need to equip the teachers with the skill sets that they need to be able to look at this material and come at it,” she says. “We can build on that momentum and interest so that there will be a continuing cohort of teachers who engage African American and Puerto Rican history.”

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Studies

More than half of Connecticut’s public school students came from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds in 2020-21, up from 44% in 2015-16. As the state’s schools diversify, and yet the curriculum remains much the same as it has for decades, momentum has been building to move K-12 education in line with its students.

Jason Oliver Chang knows the importance of building momentum. He co-founded the first Make Us Visible state chapter in January 2021, which successfully advocated for the integration of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) contributions, experiences, and histories in classrooms across Connecticut. AAPI studies will be required to be taught in the state’s K-12 public schools by 2025.

Chang, an associate professor of history and director of the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute (AAASI), has been hired as a diversity consultant in the State Department of Education’s process of building new social studies standards. The standards, which are expected to be adopted in Summer 2023, provide skill and knowledge targets for each grade level.

“I was hired to advise on appropriate measures to include Asian American and Pacific Islander studies in the occurrence of absences and the removal of problematic standards, framing, and questions,” says Chang, who launched the AAPI Advisory Board.

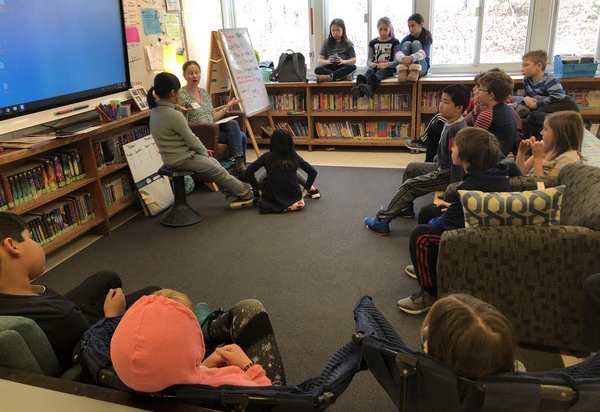

He also hosts the Advanced Pedagogy Curriculum Lab, bringing together public school teachers, principals, and curriculum developers with UConn faculty and students who aspire to be teachers.

“Sponsoring community-engaged scholarship and public-facing research has elevated AAPI work in different corners of the state’s cultural institutions and education systems,” he explains.

The AAASI created a support structure of curriculum development, scholarships for future teachers, and professional development for current teachers. Its Activist-in-Residence program is prioritizing K-12 curricula work, and through new programs, Chang hopes to get more undergraduate students involved.

“Many Asian American students want to help give the next generation of students the opportunities to learn what they missed out on in public schools,” he explains.

Liberty and Justice for All

State education advocates have been laying the groundwork for a more inclusive curricula for many years. In 2018, Connecticut passed a bill mandating Holocaust and genocide education in public schools.

Avinoam Patt, Doris and Simon Konover Chair of Judaic Studies and director of the Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life, serves on the Connecticut Holocaust and Genocide Education Advisory Committee, which provides curriculum materials and resources to assist schools with implementation.

“I’m now working with the UConn Human Rights Institute to develop a post-baccalaureate certificate to support the efforts of teachers and students committed to teaching this difficult subject,” says Patt, who is developing a new website called “Connecticut Remembers the Holocaust” with students from UConn’s digital media and design program. His co-edited book, “Understanding and Teaching the Holocaust,” also helps teachers explore new ways to approach the topics of antisemitism and postwar justice.

Noga Shemer, an assistant professor in residence of anthropology, is also focusing on human rights. She developed a K-4 toolkit for Mansfield elementary school teachers to build on themes related to events and holidays informally celebrated in the classroom.

“The program aims to deepen the schools’ culture of inclusion,” says Shemer.

Teachers are provided with a set of books and lesson plans for every month of every grade, which allows students to explore diverse, historical, and intersectional perspectives as they discuss justice, injustice, and action.

“[It] give[s] substance to the words children recite daily,” she explains. “Liberty and justice for all.”

Vernal says that although great steps have been taken toward a more inclusive history education, their work is far from over.

“It’s always been a collective effort,” says Vernal. “The students have always been the catalyst, and I don’t want us to forget that.

“They wanted to understand their histories, and why their communities look the look the way that they look.”