When you drive through a city or town and see rundown buildings or overgrown vacant lots, you may be left with a bad impression of the area. Going beyond perception, the prevalence of problematic properties within a town also typically signals that the area is economically depressed. With that comes social and environmental injustices inflicted upon communities.

Land banks could hold the key for municipal revitalization and environmental protection.

What is a land bank? Land banks are quasi-governmental organizations established by municipalities to acquire and repurpose or revitalize abandoned, vacant, or distressed properties for the good of the community.

However, many times, funding falls short, and the bare minimum of upkeep is done on properties after acquisition. Research shows there is a solution: working with communities to convert these structures and lots into properties that benefit both the community and their ecosystems.

This semester, landscape architecture students taking LAND 3330 Planting Design worked with the Hartford Land Bank to design two sites slated for affordable housing. The goal was to establish environmentally friendly, low maintenance, drought-tolerant landscapes that will enhance the biodiversity in the Hartford area to help mitigate flooding, and potentially support urban food production.

Utilizing climate-adaptive designs, these distressed properties can go from public eyesore to public benefit.

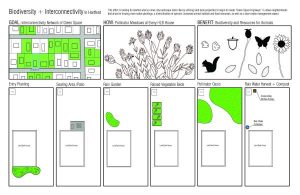

One student, Sam Bushka ‘24 (CAHNR) proposed an innovative approach of connecting backyards to create an urban pollinator pathway.

“During my research on Land Banks in the United States I found many of these sites were in neighborhoods with poor biodiversity. I wanted to use this great housing initiative as a vehicle for creating a more biodiverse city. If implemented, a network of backyard pollinator meadows can do just that.”

While towns and cities might choose different outcomes for their vacant lots, like a farmers market or open play space, one ingredient is necessary for successful transformation projects: community buy-in.

“The key is community engagement and ownership over the project,” says Sohyun Park, assistant professor of landscape architecture. “Projects must engage with various community stakeholders, such as land bank offices, local land trusts, community-based organizations, municipalities, and community members to ensure all the challenges and priorities communities have been accounted for, and to build consensus at every stage of the project development, implementation, and upkeep.”

For communities to fully invest themselves in the betterment of the vacant lots, they need to also know the properties will not be sold to private developers who will contribute to gentrification and drive them out of their homes.

A number of research studies have discovered correlations between vacant lots and unsafe physical conditions in urban areas globally. From soil and chemical contamination to mental and physical health risks, the implications extend far beyond unsightly properties, and post-industrial cities like Hartford have a growing number of vacant properties suffering from neglect. The problem is compounded by disinvestment in infrastructure and public services.

“This presents cities with an opportunity to enhance aesthetics, ecosystem vitality, and even public health,” says PhD student Zahra Ali. “People may wonder how transforming these properties can benefit human health, but it all comes down to equitable access to nature. Plants help mitigate air pollution and store carbon, in addition to adding to urban biodiversity and providing outdoor recreational space to support mental and physical health.”

Those plants could include fruit trees, vegetables, and herbs, and native pollinator plants to attract bees and butterflies. A vacant lot is transformed into a community food garden that not only feeds the humans that tend it but the other species we share our communities with. In economically depressed areas, the implications go even farther. If transformed spaces are, for instance, near a school without a playground or garden, it could provide learning opportunities and time outdoors for children who may not have access otherwise.

Experiential learning like this project also “banks” talent for the future.

“Giving UConn students hands-on experience in their communities prepares them for fulfilling careers and instills a commitment to engage with communities to build a more sustainable and just future,” says Park.

For CAHNR student Mia Tunucci ’24, their work is just the first step towards more biodiverse landscape implementations.

“Working with the Hartford Land Bank was a unique opportunity to increase biodiversity through residential projects. Creating a design that prioritizes local ecosystems while also being low-maintenance for homeowners was my top priority when working with the Land Bank.”

This work relates to CAHNR’s Strategic Vision area focused on Fostering Sustainable Landscapes at the Urban-Rural Interface.

Follow UConn CAHNR on social media