In the 1940s and 1950s, Connecticut factories were pumping out products attracting buyers worldwide: brass goods in Waterbury, silk in Manchester, munitions in Hartford and New Haven, hardware in New Britain, and many more.

But as those urban factories churned out manufactured goods, the rural poultry industry was quietly but steadily growing as well, with about 3,000 poultry farms of all sizes operating throughout the state.

And where you’d find a poultry farm, you’d find UConn Extension agents helping them thrive with answers about feeding, illnesses, egg production, and other concerns.

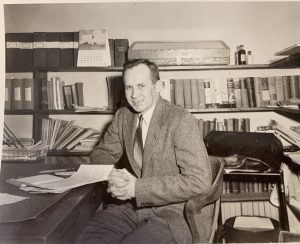

Against this backdrop, William Aho joined UConn 1952 as a new UConn Extension poultry expert and poultry sciences professor. In that role, he became an integral part of UConn’s evolution into a national leader in the field and helped set the foundation for research that continues to this day, including a federally funded project in which UConn is the lead among nine partners.

Now 105 years old, Aho is UConn’s oldest retiree and the third oldest among all state employees, according to state comptroller records. Still living locally, he’s also a fount of knowledge on UConn Extension, the Connecticut poultry industry, and the College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources.

Aho, born to Finnish immigrants in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, became interested in chickens when his family operated a farm after the Great Depression closed the iron ore mines where his father had been a foreman.

Having studied poultry science at Michigan State University before and after his service in World War II, Aho received his degree and worked there before coming in 1952 to Connecticut, where about 3,000 commercial poultry farms and three chicken processing plants were thriving.

Aho, one of the last people that UConn named to the rank of full professor without holding a Ph.D., brought more than just his poultry knowledge: Fluent in Finnish, he was able to help UConn better serve eastern Connecticut’s large Finnish-American poultry farming community.

“They came just as the poultry industry was expanding, and it was easy to get in because you didn’t need a lot of land,” Aho recalls. “They weren’t the only ones. There were many French Canadians, Jewish, Polish, Russian, and other immigrants. There were three processing plants and four egg-marketing organizations in the state, and it was a very robust industry.”

Old-time Yankee family farms statewide had been selling or trading their eggs in their local communities for years, often headed by wives and mothers as supplemental income to their households.

Those farmers were soon joined by many others, including immigrants and people who had transitioned from other professions during the Great Depression, and cooperatives were set up to collect and market the eggs on a broader scale.

Even as Connecticut chickens were pumping out eggs at a rapid pace, increasingly plump broilers were being grown on those farms and also at UConn. They appeared on dinner tables throughout New England and New York City, a new and meatier alternative to the smaller chickens better suited for the stew pot.

Already knowledgeable on the chicken industry from his education and personal experience back in Michigan, Aho was an ideal choice to join UConn as a professor and extension agent.

Like any newcomer, Aho was excited but a little nervous, though he settled in quickly: “At first, of course, I was concerned and wondering how I was going to do. It was a pretty impressive faculty to step into, but I coalesced them into a team and we went out spreading the news,” he says.

“Spreading the news” involved travel, and lots of it, and countless phone calls on all things chicken related.

He visited all corners of the state to speak at poultry farmers’ late-night meetings – they were occupied with their farms during the day, of course – and helped them identify and resolve issues in their flocks and suggesting ways in which to improve profits. Occasionally he was accompanied by his son Paul, who grew up to become a sought-after poultry economist and consultant still based in Mansfield.

“We were always on the road in one place or another,” Aho recalls. “The county agents would organize a meeting and we would go in as a team, maybe with a veterinarian and someone in ag (agricultural) economics – whatever they needed from us at the time.”

At the same time that Aho’s reputation was growing as UConn’s go-to expert on chicken farming, the modern chicken meat industry was evolving thanks in part to research by his colleagues at Storrs.

Their legacy continues to this day, including developing certain feed rations still in use; identifying a particular strain of infectious bronchitis in chickens; formulating a vaccine against certain respiratory illnesses; and pioneering chicken house ventilation.

His colleagues in the Poultry Science Department also ran the Connecticut Poultry Contest for decades, in which breeders would send in 26 pullets that UConn would house as it tracked their feed consumption, egg production, and other health indicators so farmers could assess where best to buy their next flocks.

In fact, UConn’s expertise was so widely respected that when President Albert Jorgensen declined to fund a new Poultry Science Building, the Connecticut Poultry Association went around him and straight to the General Assembly.

That body, which included many rural legislators with farmers in their districts, provided the funds for the building, now known as the Roy E. Jones Building and also often called the Nutritional Sciences Building.

After retiring from UConn in 1976, Aho directed and taught the poultry management school at Arbor Acres in Glastonbury for almost 20 years.

But it wasn’t a retirement hobby or soft landing. Rather, it was a robust second career at a company that was famous worldwide for its expertise in chicken genetics, driven by founder Henry Saglio’s development of “The Chicken of Tomorrow”: a White Plymouth Rock breed still popular today for its extra meat, quick maturation, and prodigious egg production.

Arbor Acres had such a strong reputation that managers from poultry production companies from around the world came to its classes, and Aho educated more than 500 students from 25 countries during his time there. The work also brought him around the globe to poultry operations as far away as Jordan, Thailand, China, Sweden, and other nations.

Never one to slow down, Aho learned to fly small planes at age 60, renting them in various places where he and his wife, the late UConn home economics instructor Sylvia Aho, would take vacations.

Sylvia Aho was a force in her own right, having pioneered and published works on early handicap-accessible kitchen design while teaching at UConn. They could often be seen taking near-daily walks on Horsebarn Hill, a UConn location that remains special to the Aho family.

Their son, Paul, carries on the family tradition by running his consultancy, Poultry Perspective, and is well known in town as chairman of the Mansfield Planning and Zoning Committee. His daughter, Janet Burns, also returns often to Mansfield from her home in Cambridge, Mass.

Paul and his father wrote a comprehensive overview of the poultry industry in Connecticut that appeared in a 2008 history of the Connecticut Cooperative Extension System at UConn, and Aho also gave an extensive interview in 1999 as part of the Connecticut 20th Century Agricultural History Project.

Proud of his Finnish roots, Aho embodies the iconic character trait known in that culture as “sisu” — an innate grit and determination that helps them push through the toughest parts of working, soldiering, and life in general.

But whether that’s the secret to his longevity remains unknown. After all, he comes from a hardy family line, with his mother and sister each having lived past 100. In fact, he’s part of a Boston University study on longevity.

He also avidly follows the daily news, takes frequent rides with his caregiver through campus and elsewhere in Mansfield, occasionally stopping for his favorite vanilla ice cream at the UConn Dairy Bar.

“I often feel very lucky,” Aho said in his 1999 oral history. “People say, ‘Well, how come you got into the chicken business?’ They ask me what I had done, and I tell them I was a chicken specialist – but (being) the chicken specialist took me around the world.”