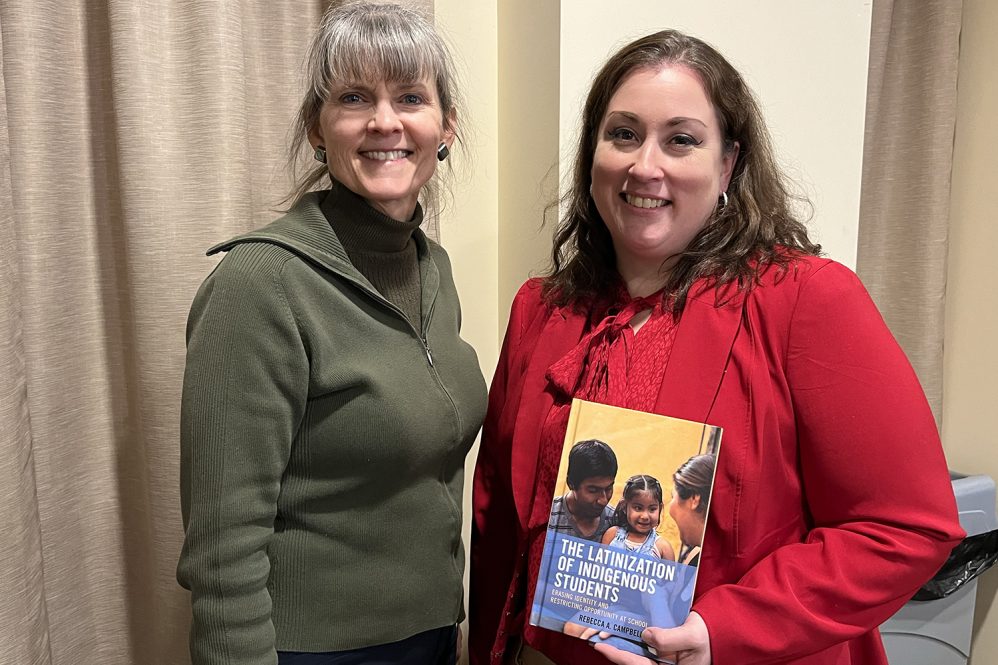

Last month, in collaboration with UConn’s El Instituto, the Neag School of Education sponsored a celebration of Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo’s new book, “The Latinization of Indigenous Students.”

Campbell-Montalvo is a cultural anthropologist and visiting assistant research professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the Neag School. In this position, Campbell-Montalvo leads a $1 million NSF-funded grant on broadening participation in STEM and investigates patient education and health outcomes.

Based on field research in rural central Florida, Campbell-Montalvo’s book explores how schools interpret and handle demographic data, potentially disregarding Indigenous identity and affecting access to resources. Her fieldwork suggests that schools may be reshaping the languages and racial identities of Indigenous Latinx students and families in school records and school employee understandings, inadvertently erasing their indigeneity.

The book launch event began with a welcome from Anne Gebelein, associate director of UConn’s El Instituto, the event’s main sponsor.

Gebelein expressed her gratitude for the collaboration between El Instituto and the Neag School, which highlights faculty work in Latino education. Gebelein also emphasized that the event was only possible due to a collective sponsorship effort between El Instituto, the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, the Department of Educational Leadership, and the Neag School Dean’s Office.

Gebelein then introduced Patricia Baquedano-López, an associate professor of education at UC Berkeley, whom Campbell-Montalvo credits for inspiration and guidance throughout the research and publication process.

Baquedano-López shared how she and Campbell-Montalvo initially connected – through a message Campbell-Montalvo posted on an online forum – and praised Campbell-Montalvo’s willingness to collaborate and share her findings with others regarding the suppression of Indigenous Mexican languages in schools.

“I remember thinking, ‘Wow, who writes a message like this, so open and generous, in the space of the academy, where we are taught to be guarded, if not secretive, about our work, particularly on our writing process?’ ” Baquedano-López said. “It was bold and a kind of insurgent message and, at its core, a humanizing message, capturing in so many ways what I have now been reading in ‘The Latinization of Indigenous Students.’ ”

It was bold and a kind of insurgent message and, at its core, a humanizing message, capturing in so many ways what I have now been reading in ‘The Latinization of Indigenous Students.’ — Patricia Baquedano-López

After reading this message, Baquedano-López continued to follow Campbell-Montalvo’s work from afar: “I have read her work with great attention and admiration, for I have marveled at her theoretical aesthetics that she has been introducing in her work in the notions of linguistic re-formation, and racial re-formation.”

Baquedano-López explained that Campbell-Montalvo’s work and new book resonate with her because of its similarities to the work Baquedano-López does with California’s Indigenous immigrants, who undergo a similar colonizing process of Latinization in schools.

“Learning through Rebecca’s work is the principle that, like all students in our schools, Indigenous Latinx students deserve equal and supportive access to education where they can be recognized for having valuable assets that they have, assets that they bring to our schools, including rich Indigenous heritage and multilingual skills,” Baquedano-López said.

Following Baquedano-López’s remarks, Campbell-Montalvo began a book overview presentation, delving into the chapters and their significance and takeaways for educators. Campbell-Montalvo suggested that if readers choose to read only one chapter in the book, they should read the introduction as it summarizes and lays out all the arguments.

Campbell-Montalvo then discussed the research process behind the book, which included ethnographic observations over 10 months between 2014 and 2015. These observations included 100 interviews at two elementary schools.

“I observed for several weeks in their offices and community events,” Campbell-Montalvo said. “I did 46 interviews, with a majority group being Indigenous Latinx families. I did a focus group with migrant advocates. I did three surveys. One had about 1,300 responses.”

Campbell-Montalvo shared that when she conducted a language survey with more than 1,300 students and compared their results to school records, she found that “for every 19 children whose parents spoke an Indigenous language, the school recorded only one.”

For every 19 children whose parents spoke an Indigenous language, the school recorded only one. — Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo

“You’ll see that school records only showed one Indigenous language at all, Mixtec, but when I did the survey, there were at least eight languages found,” Campbell-Montalvo said. “Moreover, the total number of languages purportedly spoken by parents, according to schools, was only 13, but my findings showed that there were 29.”

Campbell-Montalvo explained that this research demonstrates that schools misunderstand the languages and identities of their student population and community demographics which inhibits their ability to adequately serve these students.

Additionally, by failing to recognize the diversity of the languages present within their communities, these schools act as an arm of colonialism and reinforce social reproduction in schools, Campbell-Montalvo said.

Campbell-Montalvo ended her talk by explaining that, although her book cannot end all linguistic suppression, she hopes this work acts as a catalyst for a broader investigation of linguistic discrepancies on a broader scale.

“Some of these concerns, unfortunately, are going to continue to be issues,” she said. “There are ongoing problems with the census that, hopefully, my work contributes to understanding. So, I’m working with some colleagues to consider looking at this in Illinois to see if we can talk about the generalizability of this.”

Campbell-Montalvo also discussed other paths forward, including ensuring that the teacher body is representative of the community served, which could be made possible through prioritizing hiring from the community.

To learn more about Campbell-Montalvo’s research and her book, including obtaining a coupon code to use when purchasing the book, email rebecca.campbell@uconn.edu.