Jackson Somers spends a lot of time thinking about trash.

As an environmental economist and assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Somers’ work focuses on waste systems in the U.S.

“I think one reason I like what I do is that it’s not something you think about,” Somers says. “You just do it. You throw your stuff away…but no one really sits there and goes ‘man I really throw a lot of stuff away.’ When you take that garbage bag out to your trash can, that’s just going to go sit in a hole – forever. And that’s not something we think about and not something we care about and I don’t know why.”

Somers had no intention of studying environmental economics during his Ph.D. at the University of California, San Diego. But when he took a class on the subject to fulfill a requirement, his professor started talking about electricity markets on the first day and Somers was hooked.

“I thought it was totally fascinating,” Somers says. “It was just really cool to see a real-world application of what we do.”

Somers’ research has covered topics including recycling, ash disposal, food waste, and composting with the goal of answering one big question: “What should we do with our trash?”

“I have not found anything near a satisfying or complete answer to that question. Given where we’re currently at in the United States, ‘what do we do, going forward, with our waste infrastructure?’” Somers says.

The Cost of Composting

In a study focused on the city of Austin, Texas, Somers analyzed the impact of their composting program on methane emissions.

When food waste goes to a landfill, it decays rapidly, producing the greenhouse gas methane. But when food scraps are composted, they are aerated and watered, preventing bacteria from producing so much methane.

Austin residents already had access to yard waste composting, but the program Somers studied expanded access by allowing residents to throw food waste to the same bin. There was a 25-30% increase in the weight of composted material with this change.

However, only about 30% of residents participated. But those who did composted everything they could.

“You had this fracturing,” Somers says. “You didn’t have an in-between where some people do some of it but not all of it. It was very all or nothing.”

This opened the next question which is whether composting programs – which are expensive – are economically worthwhile for municipalities.

While costly, there are significant benefits from preventing methane being emitted into the atmosphere that result from composting programs. These benefits are calculated according to the “social cost of carbon.” The social cost of carbon is the calculated economic impact of one additional ton of carbon dioxide being emitted into the atmosphere.

The benefits of composting programs may be compared to other, less expensive, environmentally beneficial programs, like fixing leaky natural gas pipelines.

“If your government is deciding where to put its money, maybe there are better programs,” Somers says. “But it depends on the context. For some cities [composting] really might be worth it, and for others it might not.”

Somers is also looking at if composting programs, which allow people to dispose of food waste more sustainably, reduce food waste overall by comparing cities which have programs, such as Austin, Seattle, and San Francisco, with those that do not.

“When food scrap diversion becomes mandatory, does it actually make you more aware of how much food you’re wasting, and does it affect how much food you buy?” Somers says.

Somers is also studying the impact of a food diversion mandate in California which requires large food generators, like grocery stores and processing plants, to donate edible food to organizations like food pantries and soup kitchens. But the mandate does not provide support for the food recovery organizations to pick up the food.

Somers wants to investigate the impact of this policy on the organizations, looking at how much food they receive and what proportion is not actually edible.

“There are reputation concerns as well,” Somers says. “If you go pick up this food and you see spoiled food, you’re not necessarily going to reject it because then the retailer is going to say, ‘never mind, we’ll just stop giving you this food.’ So, there’s this really interesting relationship.”

Somers has applied for a grant to study a similar question in Connecticut working with a UConn nutritionist to analyze the nutritional quality of donated food.

Improving Recycling

Recently, Somers has been working with The Recycling Partnership, a non-profit organization that educates the public about which items can be recycled and which cannot. Looking at Jacksonville, Florida, Somers found the program increased the amount of correctly recycled material by 25%.

“It’s very effective in terms of getting people to recycle better,” Somers says.

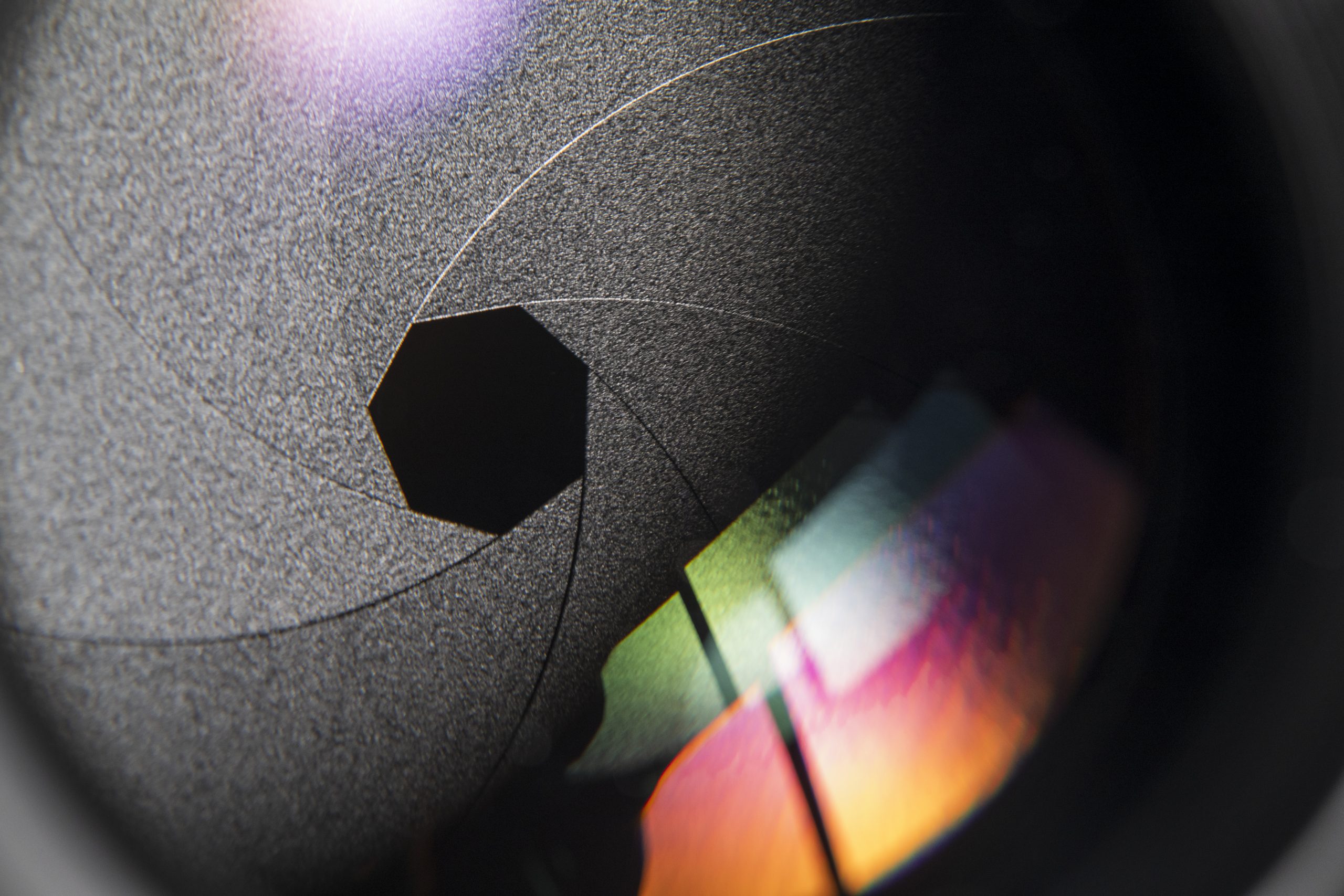

The next stage of the project will use recycling trucks fitted with cameras enabled by AI to automatically detect contaminants from recycling bins as they are being dumped into the trucks.

Local Waste Issues

In Connecticut, Somers is looking at the impact of the closing of MIRA, the waste-to-energy facility in Hartford. The facility, which closed in 2022, took about one third of Connecticut’s trash. This waste is now being shipped to Ohio.

This is setting the stage for potential problems between municipalities and waste haulers, who will likely ask for higher pay since they need to take the waste much farther.

Somers is developing a report for the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities on the potential impacts of this massive change to the State’s waste infrastructure.

Regardless of the context, it’s clear that the old adage holds true for Somers: one man’s trash certainly can provide a treasure trove of research discoveries.

This work relates to CAHNR’s Strategic Vision area focused on Advancing Adaptation and Resilience in a Changing Climate.

Follow UConn CAHNR on social media