In the town of Sitka, Alaska, local Native Americans take small boats and airplanes to spend a week getting fitted for brand new dentures at a clinic staffed by UConn School of Dental Medicine faculty and residents.

Since 1997, Dr. Thomas Taylor, professor and chair of prosthodontics, and Dr. John Agar, professor of prosthodontics—along with rising third year prosthodontics residents—have traveled to Sitka nearly every June to deliver new smiles to a population that otherwise might never receive proper dental care. To date, over 800 dentures have been made.

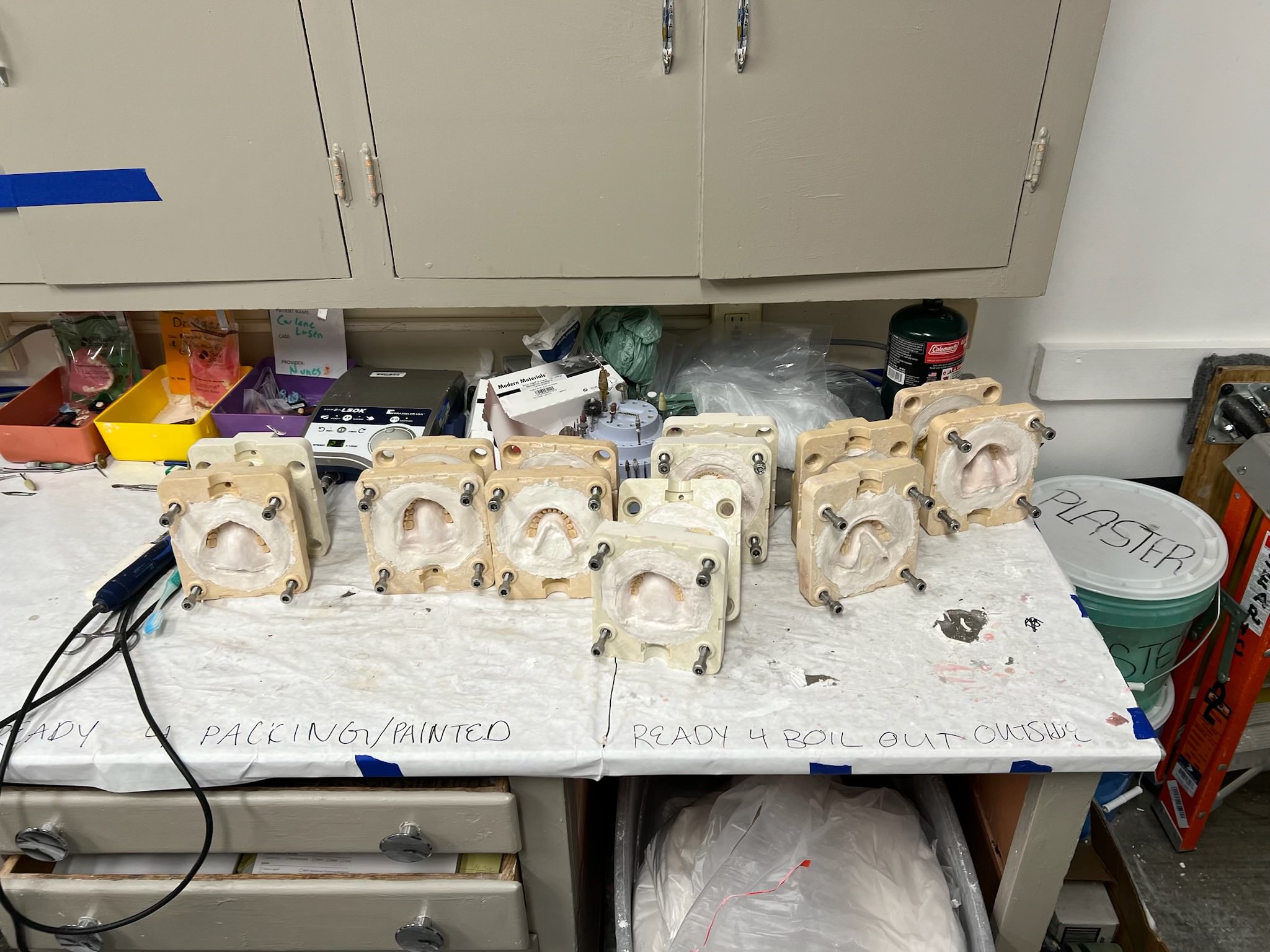

Using crab boil pots on a small burner—a far cry from the cutting-edge technology back home in Farmington—the team from UConn use the “boil out” method to fabricate dentures. After the patient gets examined, a mold is created, and wax gets poured into the mold. The wax is then heated and melted, forming the denture in the mold. The patient is seen several times after the initial fitting to ensure the denture fits perfectly with no soreness or other issues.

“Making dentures is a minimum four appointment process. It is very labor intensive, and we don’t have the equipment we have in Farmington,” says Taylor. “People think we’re boiling crabs, but we’re making dentures. It’s archaic, crude, but the outcome is incredible—the patients are very gracious people and appreciative people of what we do.”

Over four decades ago, the Academy of Prosthodontics started a program in different parts of the country to deliver dentures to underserved populations. In 1993, the program landed in Juneau, Alaska with a general dentist from Oregon and member of the South East Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC), Dr. Thomas Jordan, at the helm. In 1997, Taylor joined Jordan, and in 2003 the clinic moved from Juneau to Sitka.

Since the program’s inception, Jordan has meticulously handled all the logistics of organizing all the local patients and making sure they are able to get to the island and stay for the entire week. Jordan also follows up with the patients as necessary after the week comes to an end. According to Agar, it is a massive undertaking.

“The logistics is a big problem—planning, organizing, and getting the patients lined up. If you have any glitches—you only have that week to do it and every minute is accounted for. We must be at a certain stage at a certain time,” explains Agar.

Jordan is retiring this year after 31 years of running the program, meaning that this summer was most likely the last for the program that has helped transformed the smiles of hundreds of Native Americans. There is no appointed successor, and no one locally is willing to take on the massive responsibility.

Understandably, this is bittersweet for Taylor and Agar. While sad that the program is ending, they are full of countless memories of the people that they’ve helped along the way.

Taylor fondly remembers one patient that had a bite so disjointed, he asked him if he broke his jaw. “He said, ‘Yes! You’re the first dentist to ever ask me that.'”

“We made him the ugliest looking set of dentures, and he absolutely loved them,” recalls Taylor. “He went out and ate a steak the first night—which we advised him not to do—and he came back the next morning saying how much he loved them, had no sore spots. He was so appreciative.”

Every year, Taylor and Agar bring a cohort of 3-4 prosthodontics residents that just completed their second year of residency, and one other clinician who is also a member of the Academy with SEARHC and the Academy of Prosthodontics footing the entire bill. The trip is a big hit among the residents, as they always come back and—very excitedly—share their experience with incoming residents.

Not being able to take residents to Alaska is one of the harder parts of the program ending, according to Taylor and Agar. It has become an expectation, and everyone looks forward to the trip the moment they begin their residency at UConn.

Dr. Audrey Brigham, a second-year resident, was part of the final group that returned a few weeks ago.

“It was an absolute honor to be a part of the last group of UConn Prosthodontics residents selected to represent our program at a rural hospital in Sitka, Alaska to volunteer in fabricating dentures for individuals in need,” Brigham says. “Throughout the process, the residents learned the importance of adaptability and patient-centered care, gaining valuable insights into the unique dental needs of rural populations.”

To Brigham, the experience will leave a lasting impression as she continues her career as a prosthodontist.

“Participating in this volunteer outreach program was a transformative experience for both the resident doctors and the patients. For the patients, many of whom had limited access to dental care, receiving custom dentures was a life-changing event, significantly improving their quality of life and self-esteem. For the resident doctors, the program provided a rare opportunity to apply their specialized skills in a real-world setting, fostering professional growth and a deeper appreciation for community service.”

Brigham continues: “This once in a lifetime experience emphasized the profound impact of dental care on individual lives and highlighted the critical need for continued volunteer efforts in underserved areas. I am more than grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in this outreach program- and I cannot emphasize enough the absolute impact the experience has on each and every resident that attends.”

When asked if there are any plans to ever return to Sitka, especially after spending a week every summer for nearly three decades working tirelessly to deliver an average of 30 dentures per trip, Taylor and Agar looked at each other and smiled.

“Yes, we’re planning a fishing trip,” Taylor remarked.