UConn’s College of Engineering’s (CoE) Connecticut Advanced Pavement Laboratory has successfully completed training for its first cohort of participants in a pilot program coordinated with the Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT), the Connecticut Department of Correction (DOC), and the Connecticut Asphalt and Aggregate Producers Association (CAAPA), designed to train incarcerated inmates in asphalt production and product testing. The program is being managed by CoE’s Connecticut Transportation Institute (CTI), which serves as a focal point for transportation-related research at the University, and training throughout the state.

The five initial participants have each received employment offers within the transportation and road-construction sectors contingent upon completion of their sentences, and the DOC has already requested that a second cohort be trained.

“This is a good career opportunity since these jobs must be done locally and won’t be replaced by automation, and jobs in this field pay well,” CTI Educational Program Manager James Mahoney says. “It’s clearly a ‘win-win’ for employers, the DOC, and incarcerated individuals soon to be released, who often have trouble finding good jobs.”

Mahoney and Alexander Bernier, along with CTI Research Assistant Scott Zinke, worked with the Connecticut Asphalt and Aggregate Producers Association to design and conduct the training. The program, Mahoney explains, had been in development for some time, with the dual goals of aiding the asphalt industry to fill much-needed asphalt testing positions while also helping incarcerated individuals develop skills that could immediately be applied in paid positions when their sentences had been completed.

The grant funding for this training was through the DOT. The DOC identified potential trainees internally, Mahoney says, and the training was partially conducted in a professional-development center within the Carl Robinson Correctional Institution. Part of the challenge, Mahoney adds, was devising training methodology that could be instituted at the correctional institution rather than at asphalt production facilities or at actual paving projects in the field where this training would normally take place. As a result, they had to reinvent the way the training could be completed. DOC came up with a list of vetted participants who were scheduled to be released in the near term but would remain in corrections long enough to go through the training program. Ten two-hour sessions were conducted, six at the prison, one virtually, and three at the CTI lab at UConn.

In Connecticut, the DOT spends in excess of $200 million a year on average paving roads, Bernier explains, so having enough trained individuals to perform required inspection and testing is a priority for all stakeholders. The trainees, he adds, were very engaged in learning and, upon nearing program completion, attended a mini job fair attended by asphalt industry representatives. All five, he says, had job offers pending their release.

Zinke says asphalt training programs are rare, and usually conducted by employers with previously untrained individuals; there aren’t programs in trade schools or other venues to learn about asphalt training. “The added value here,” he says, “is that employers realize that every time they bring someone through the door, they’re more than likely going to have to train them from scratch. Nobody tests asphalt at home in their kitchens . . . it’s highly specialized and requires proper training, equipment, and testing facilities, so this is giving our trainees a leg up once they are able to work in the industry.”

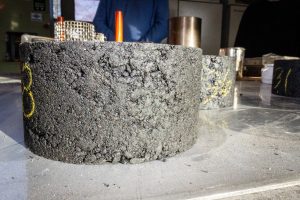

The CTI team, who together share close to 80 years of combined paving experience in the field, provide hands-on instruction at the Connecticut Advanced Pavement Laboratory using presentations, photographs, and videos as well as asphalt samples, and offer exposure to testing materials and tools. The trainees learn and physically demonstrate standard AASHTO and ASTM testing procedures and participate in multiple hands-on exercises. They also study the composition of different kinds of pavement, Zinke explains, which typically are 95% sand and stone and 5% liquid asphalt binder.

“They learn about composite materials and what the specific aggregate testing requirements are,” Bernier adds, “the liquid asphalt binder, how it’s handled and what the temperature grades are and then, ultimately, how it all goes together at the facility in order to get a quality product at the end of the day.”

The result of this training is helping to create a much-needed pipeline of skilled testing professionals. Asphalt training, the trio explains, often is a foot in the door, and can lead to growth into many other areas such as concrete testing and field-inspection assignments, as well. And most importantly, these kinds of programs can be beneficial to all parties.

“Interestingly,” Bernier reflects, “if you talk to people in the asphalt world, most of them end up there by accident, but they all like it and they tend to stay there. When I was going to school, asphalt work was the furthest thing from my mind. But there’s actually a significant need for trained individuals, as mandated testing and inspection occurs whenever there’s state or federal dollars being used for roads, and there’s a shortage of skilled testing professionals.”

Ultimately, all agree, this program, and similar efforts, are about ensuring that people have opportunities to succeed when they leave the penal system. The DOT is extending funding for at least another year; a second session is now being planned, and coordinators are looking at other opportunities within the construction realm that can be beneficial to all parties.

More information about the Connecticut Transportation Institute is available online.