On Friday, November 15th, Marlene Schwartz spoke on a panel at “Food & Nutrition Insecurity in Connecticut: Challenges and Opportunities.” The event, which was hosted by the CT Commission on Women, Children, Seniors, Equity & Opportunity (CWCSEO), was held at the Legislative Office Building in Hartford. Schwartz is the director of the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health and a professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences. We spoke with her following the event to learn more about food insecurity in Connecticut.

How are food and nutrition insecurity defined?

Households are considered “food insecure” if they do not have consistent access to enough food for all family members to live an active, healthy lifestyle. A newer term is “nutrition security,” which takes this concept one step further and looks at whether individuals have sufficient access to nutritious foods.

What can be done to improve nutrition security?

At the event, I shared some of the research we have done in Connecticut that shows how important nutrition is to people who are seeking food at a food pantry. Our state’s food bank, Connecticut Foodshare, has been working for years to maximize the nutritional value of the foods they provide. In addition, several of the other speakers at the meeting talked about Food as Medicine efforts in Connecticut. These initiatives focus on providing fresh produce and other nutrient-dense foods for people who are experiencing food insecurity and chronic diet-related diseases, like Type II diabetes.

What support systems are in place to help families in Connecticut facing food insecurity?

Several people from our state government agencies were at the meeting to talk about federal food programs that are managed by the state. Key programs include: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP). One interesting fact about school meals is that costs to families are based on income, and typically there are three categories: paid, reduced-price, and free. In Connecticut, families that meet the income level for reduced-price meals actually receive them at no cost, which is an important way to increase access. Other states like Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine have taken the additional step to provide school meals at no cost for all children, but so far, Connecticut has not done that.

One topic that was brought up at the event was the importance of treating people seeking food assistance with respect and ensuring their dignity. Why is that so critical?

Historically, some parts of the charitable food system measured success only by the number of people served and volume of food distributed. Over the past few years, however, there’s been a shift towards looking at success more holistically. Part of this is ensuring that every person seeking food assistance is treated with respect at all stages of the process. Is the shopping environment at food pantries set up so neighbors can select the products they want? Are partners using respectful and compassionate language in their interactions with neighbors and on all printed materials? Is the space inclusive and accessible for people from all backgrounds? At the meeting, we heard from people who have lived experience with food insecurity. Their stories about the innovative ways in which food pantries are making neighbors feel welcome and supported can help guide our strategies moving forward.

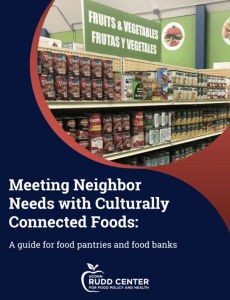

You also mentioned the Rudd Center’s “Cultural Foods Guide” that can be used by food banks and food pantries. Can you share how that initiative can help members of the charitable food system serve people more holistically?

Part of treating people with respect is also offering foods that match their needs and preferences, which we refer to as “cultural foods.” To better understand what cultural foods are, think about the foods your family made for you growing up or the recipes you want to pass down to your children. These dishes and ingredients hold a special place in the hearts of a community. Earlier this year, the Rudd Center created a “Cultural Foods Guide” with the support of the Society of Public Health Education (SOPHE) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). This guide equips food banks and food pantries with the tools they need to survey their neighbors about the cultural foods they are looking for. Hopefully, partners can utilize the guide to more fully meet the food and nutrition needs of their neighbors.