UConn and the five recognized American Indian Tribes within current State boundaries are launching a historic partnership, envisioning wide-ranging collaborations in academic and research pursuits, economic development, community service, and cultural enrichment.

Such a comprehensive agreement is the first of its kind on the East Coast between Tribal Nations and a university. It is especially significant given UConn’s status as one of the federal Morrill Act land grant institutions, which profited from land obtained from Indigenous peoples through generations of broken treaties, forced removal, and brutal warfare.

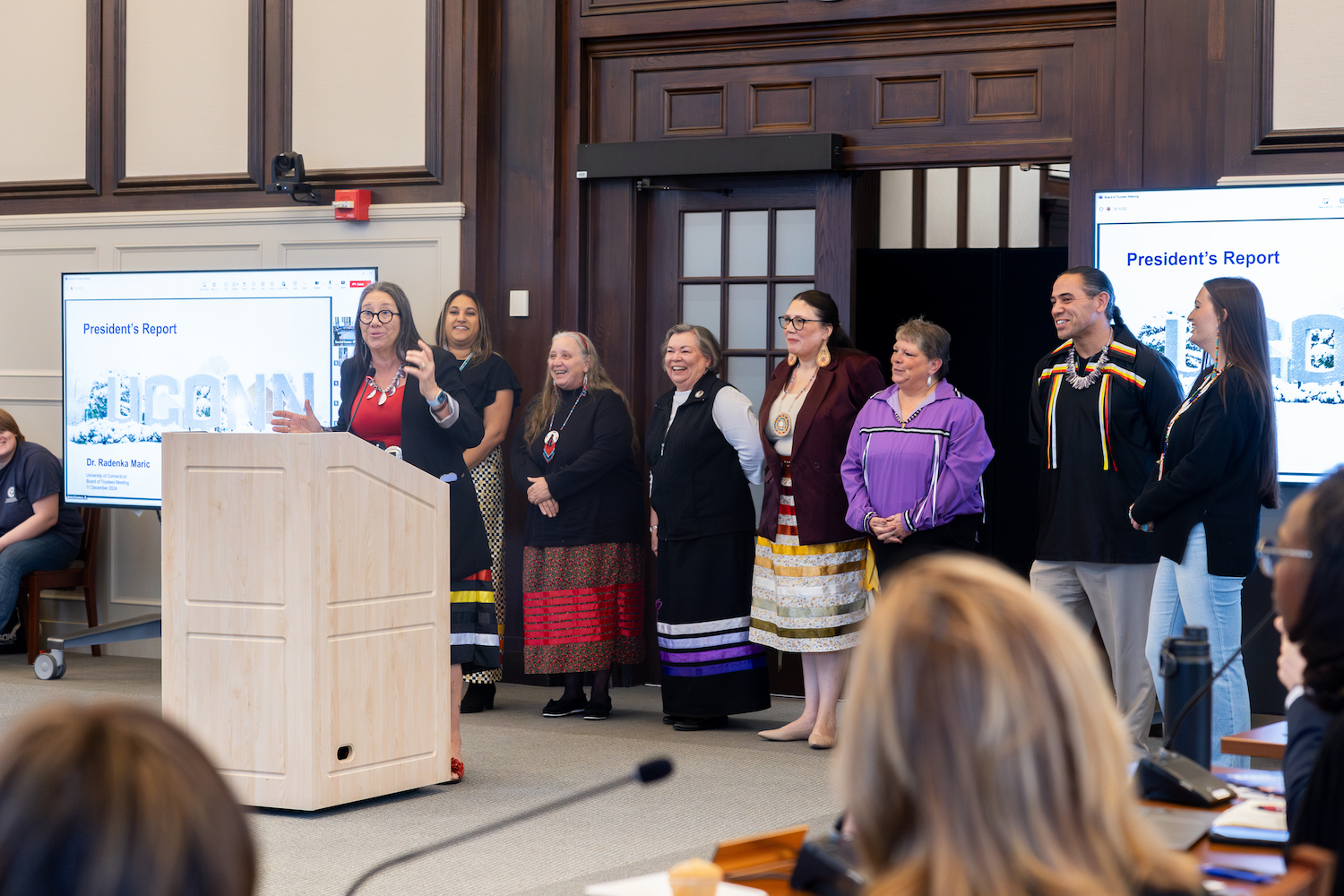

The Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) was met with applause, embraces, and more than a few tears of happiness when it was presented recently to UConn’s Board of Trustees by citizens and representatives of the Eastern Pequot, Golden Hill Paugussett, Mashantucket Pequot, Mohegan, and Schaghticoke Tribal Nations.

“Like all land-grant institutions, UConn carries a complex history: a history of impact and achievement that rests on the displacement of Indigenous communities from the very land that sustains us,” Provost Anne D’Alleva told trustees.

“Acknowledging this history is vital as we work to fulfill our values as an institution and build meaningful, mutually beneficial relationships with our Tribal Nations, who have called this region home for generations,” she added.

It also marks a watershed moment for UConn as it seeks to position UConn Avery Point as a Native American-Serving, Nontribal Institution (NASNTI), a federal designation earned when at least 10% of the undergraduate population of a campus identifies as Native American and/or Alaska Native.

That would make UConn only the fourth institution east of the Mississippi River to have a campus with NASNTI designation and among land grant and R1 (high research activity) universities.

UConn has worked in recent years to support the development of services and programs for Native American and Indigenous students and employees. It has also established a fruitful partnership with the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation on the development of the tribe’s hydroponic Meechooôk Farm; research into responsible gaming; and various academic and cultural endeavors with the other Tribal Nations.

Those initiatives set the foundation for many more that are envisioned through the MOA, which also sets up a Tribal/University Advisory Board and commits to formal consultation between UConn and the five signatory tribes on a range of academic, cultural, community, and operational priorities.

Connecticut, whose name is derived from the Algonquin word Quinnehtukqut – meaning roughly, “beside the long tidal river” — will benefit for generations to come from the expertise and commitment that the tribes and University will bring to bear, officials said.

“Connecticut: It’s a word of our founding language. How appropriate that the flagship university that bears this name will be the first college that respectfully involves Tribal Nations here, today and beyond, to teach and learn about ourselves on our own land, including our language, history, politics, arts, and sciences,” Elizabeth “Beth” Regan, chairwoman of the Mohegan Tribe Council of Elders, said at the trustees meeting.

“At the same time, we will bring our Indigenous knowledge of the ancient stories and ways of this land, as well as the Native perspective on Connecticut in an informed way from its first peoples,” she said.

The MOA also includes strategies to increase recruitment, enrollment, and retention of Native American and Indigenous students throughout UConn and especially at Avery Point.

That campus is near some of the earliest and bloodiest 17th century engagements between the English and Indigenous peoples, which set the stage for broader colonization throughout North America and created societal and economic ripple effects that continue to be felt today.

The 1638 Treaty of Hartford, which ended the Pequot War one year after the Mystic massacre, included terms that attempted to effectively eliminate the Pequot Nation. Its language was banned, its 200 remaining tribal members were sold to other tribes, and even its name was stricken from use.

That history makes one part of the MOA between UConn and the Signatory Tribes especially noteworthy: Through the agreement, UConn joins the state and federal governments in recognizing and respecting the distinct, inherent, legal, and political sovereignty of the Tribal Nations with their own powers of self-governance and self-determination.

“I could not be more proud of my alma mater. I bleed blue, and standing here before you all is an incredibly proud moment for me personally,” Rodney Butler ’99 (BUS), Chairman of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, told trustees at the recent meeting.

“This is not simply a partnership that the University is entering into. It is a direct relationship between governing bodies that recognizes and respects tribal sovereignty for the first time in the history of this institution,” he added.

“That alone makes this moment historic, but it also makes UConn the first university in the eastern United States to sign an MOA with Tribal Nations – and more specifically a land grant institution to sign an MOA with Tribal Nations.”

A Complex History

The Storrs Agricultural College, the precursor to today’s UConn, was designated Morrill Act land grant status in 1893 after the state legislature transferred that designation from Yale.

Holding land grant status has always come with financial benefits for the original 57 institutions established under the first Morrill Act, either directly granting them property taken from Tribes for that purpose – most common in the western U.S. – or sharing the profits of seizing gained from selling that land.

While the properties on which UConn’s campuses sit had gone through generations of ownership changes before gaining Morrill Act status, the University still directly benefited – then and now — from the land seizure practice.

According to High Country News, which conducted a sweeping analysis in 2020 of the Morrill Act’s legacy, Connecticut benefited from sales that took land from more than 50 tribes. For UConn, that meant millions of dollars granted over time when adjusted for inflation.

But even before the Morrill Act was established in 1862 – and long before UConn started to benefit from it — the Tribal Nations of Quinnehtukqut had already experienced more than 200 years of dispossession from their ancestral lands, while watching the process replay itself in the western U.S.

Connecticut was once home to a large number of thriving tribes of all sizes, but as English presence expanded, tribes lost their land through warfare, treaties, and forced displacement and assimilation. Once the state was formed in 1788 and eventually thrived, the Tribal Nations fought to keep their languages, modes of governance, cultural identities, and traditions alive.

The same occurred at UConn: Even as it grew throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the percentage of students who identified themselves as American Indian and Alaska Natives rarely reached half of 1% of the entire student body in a given year.

In recent years, however, UConn leaders and members of the Tribal Nations say they’ve noticed a palpable shift.

In 2018, Penobscot student Sage Phillips ’22 (CLAS) founded the Native American and Indigenous Students Association (NAISA) in collaboration with faculty involved in the Native American Cultural Programs. The University also adopted a land acknowledgment statement in 2019 and, earlier this year, hired its first NACP director, Chris Newell ‘14 (BUS), who is Passamaquoddy.

“Our university, like the rest of our state, exists because we sit on Native lands and territories. Our histories are intertwined and marked by pain, loss, and dispossession,” President Radenka Maric said recently upon presenting the MOA to trustees.

“That’s why I’m so deeply honored to recognize this Memorandum of Agreement, (which) will focus on our shared commitment to education, community-engaged research, economic development, and opportunities in Tribal Nation communities,” she said.

A Path Forward

Tribal leaders, university faculty and administrators, and others have worked for the last two years on developing the Memorandum of Agreement.

People and groups from throughout the University have been deeply involved in the discussions with Tribal members from Connecticut and beyond including the Provost’s Office; the Akomawt Educational Initiative; the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources; and Professor Sandy Grande, who is Special Advisor to the Provost for Native American and Indigenous Affairs and a professor of political science and Native American & Indigenous Studies.

Throughout the process, they said, they did not want a document heavy on rhetoric and short on action.

On the contrary, it has specific aims that include working together on ideas to recruit and retain Native American and Indigenous employees and students; working to imbue UConn’s academic, research, and service missions with meaningful elements of Native American knowledge; and identifying potential collaborative business opportunities with Tribally owned businesses.

The new Tribal/University Advisory Board will be tasked with meeting at least four times annually to set strategic priorities, receive updates, and ensure an active, vibrant, ongoing conversation among all of the parties.

“As this nation is approaching the commemoration of its 250th year, our tribes and the University of Connecticut will be leading on the right side of history,” Regan said.