In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

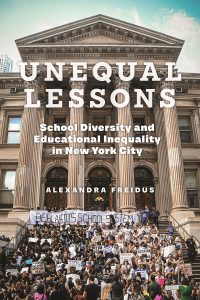

Alexandra Freidus, assistant professor of educational leadership, recently published a new book through NYU Press, “Unequal Lessons: School Diversity and Educational Inequality in New York City,” which highlights the experiences of young people as learners and policy actors to reveal the potential and limits of school diversity as a path to educational justice.

Freidus teaches graduate-level courses on educational policy and qualitative research; has received numerous honors, such as a Spencer Foundation Racial Equity Research Grant and an American Institutes for Research Grant; and has published 14 journal articles. She completed her Ph.D. in urban education at New York University, her master’s in education from Mills College, and her bachelor’s in history from Brown University.

Freidus’ work focuses on using participant observation, interviews, and public archives to explore how community stakeholders understand student diversity; how school and district administrators implement education policy; and how these interconnected dynamics shape the core mission of schools: teaching and learning.

In this feature, we learn how Freidus’ new book explores the importance of school diversity and the path to educational justice in New York City schools.

Q: Where did the inspiration for this book come from, and how long was this in the works for?

A: This book has been in the works for a really long time. I have been formally doing research contributing to the book for over 12 years now, while the inspiration for the book came from when I was a teacher roughly 20 years ago. The school where I taught had a very spatially, ethnically, linguistically, and socioeconomically diverse group of students. I was excited over the wide range of experiences students brought, but struggled with figuring out what it meant to lead a classroom where people were coming from so many different places. It’s that particular question of how to balance those two that motivated me to get my Ph.D., and would eventually become my dissertation, which comprises half of this book.

Q: How did you get involved with NYU Press?

A: I was particularly excited about NYU because the book’s research was conducted in New York City, and I knew that the NYU staff would have a good understanding of what that meant, what it entailed, and especially how to connect the book to the audience.

Q: How did you conduct research/collect data for this book?

A: It was really important to me that, before I went into the schools, I understood what was happening in the communities. When I initially started this research, there was a lot of coverage in the press about segregation in New York City public schools, largely due to a report from the UCLA Center for Civil Rights.

I began attending community town halls and public meetings, eventually connecting with one district that permitted me to conduct research. I started going to their meetings to understand who was involved in the conversation around school diversity in New York City, their differing perspectives, what they hoped greater diversity would achieve, and what concerns they had.

Then I spent a year alternating between two schools, spending time with the students and teachers. As I wrapped up my dissertation, I realized I wanted to better understand what students were thinking about segregation and diversity.

I reached out to Teens Take Charge, which is a student community organizing group that was working on school segregation in New York City. In establishing a partnership with them, I started going to all their meetings and talking to these high school students about their experiences and observing the work they were doing in their communities to raise awareness.

Q: How do you feel now that you’ve completed this book?

A: I’m excited. I’ve worked hard to write the book in a way that goes beyond traditional academic writing, which is directed toward academics for teaching purposes. It was important to me to write it in a way that would be accessible to parents and school staff, who may not have as much time to read. And from what I’ve been hearing from people who have read it, I achieved that goal, which is pretty exciting to me.

It was important to me to write it in a way that would be accessible to parents and school staff … from what I’ve been hearing from people who have read it, I achieved that goal, which is pretty exciting to me. — Alexandra Freidus

Q: What have you learned through the writing process that surprised you? And how might this compare with other projects you’ve been involved with?

A: I’m interested in research that speaks directly to people who are working in schools, and in forming partnerships with those people, and in making sure that the research studies find useful information for those people. And while those were things I was interested in before I wrote the book, I wasn’t clear on the steps that were involved in doing that work. I knew it would be hard, but I wasn’t clear on all the ways it would be hard.

I think educational research has been good at diagnosing problems, and not as good at offering ways that people can address them. So, thinking critically in partnership with people to talk about what should be done differently has been challenging but also useful.

Q: What is the relevance of this research, given the current academic climate?

A: If we think beyond the academic climate to the political climate, there are a lot of arguments about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) right now. In my experience, both sides of the argument tend to be pretty simplistic. They’re more focused on making certain political points, and in some cases, upholding white supremacy, than thinking through what diversity is actually doing.

I get worried that in our climate, people are getting asked to defend pretty basic educational practices like representing kids’ racial or cultural backgrounds. They are getting attacked. I think it’s important to recognize that this work can be important, and also not solve all our problems. In the book, I consider what the goal is, which would be to advance racial justice and to make sure that every kid gets the schooling they deserve.

Q: How has working within the Neag School of Education broadened your understanding of educational leadership?

A: It’s been enormously helpful. I learn so much from my students, most of whom work full-time in Connecticut schools. It’s my job to teach them about educational policy, politics, and how to do research. And I do that by learning about their experiences so that we can connect them back to the topic of the course. So, I’m teaching them, but in the process, I learn so much about the challenges they’re experiencing in varying contexts. Having the chance to learn about what they’re grappling with and to think through the strategies they’re trying out has been truly rich for me.

Q: How does understanding the history of desegregation matter to the impact we see today?

A: I think you need to understand the history to understand where we are now. In particular, many advocates (but not all) for school desegregation, and in particular, the Brown v. Board of Education decision, really assume that it’s important for all kids to have access to white kids and white resources.

The Brown decision was important in that it gave African American communities, in particular, access to materials and resources that they didn’t have. Fast-forwarding to today, we have a situation where schools such as the ones in New York are scrambling to retain white families and students by accommodating them because that is the way they believe they are going to attain what they need. This context helps us understand why trying to diversify schools does not, on its own, often achieve racial justice.

Q: What are some of the bigger challenges students, parents, educators, and policymakers face as a result of school segregation? What can be done to address this educational inequality?

A: People end up, without meaning to, making all kinds of accommodations to serve white students, who are trying to get into the school to attain more resources. What that ends up looking like is dramatic differences in school discipline, such as how white kids are treated compared to other kids at the school. Or academic tracks correlated to race, in terms of which kids get placed in honors and AP courses and which don’t.

Nobody goes into school saying, “I want to be racist,” and this is not about individual educators doing something wrong; it’s that we live in a society that elevates whiteness. Schools are a part of that society. Hence, they end up reproducing some of these problems – and making them worse, because kids end up watching and internalizing these patterns, which further perpetuates the cycle.

Q: What do you hope the larger audience takes away from this book?

A: I would like them to think about what it is they are trying to achieve in the sense of racial justice. What are their actual long-term goals? Then what are the strategies? That may be diversifying schools, but does that serve a larger purpose of restructuring our racial order? I think more specifically, I hope that educators will look hard at their classrooms and their own schools to ask how the systems in place and individual actions are impacting kids. I would hope that families who are choosing schools can start to ask those same questions to not only think about what is best for their children but also recognize that what’s happening to other students affects their children. More broadly, I hope that community members would be thinking about the roles schools play in racial inequality, and what roles they could be playing.

To learn more about Alexandra Freidus’ research, email her at alexandra.freidus@uconn.edu.