This article was first published in the Hartford Business Journal. Dr. Christine Finck, a pediatric surgeon at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and associate professor and principal investigator at UConn Health, was recently named as one of nine Health Care Heroes in Greater Hartford. The title recognizes individuals working in health care who “share a common passion for the services they provide and life-changing impacts they have on the lives of others,” and “[make] a difference in the community every day.” Finck and her fellow award-winners were honored last month at the Connecticut Convention Center in downtown Hartford.

As a pediatric surgeon, Dr. Christine Finck sees her share of babies born with esophageal atresia, a defect where the tube between the mouth and stomach fails to connect. Finck treats up to a dozen infants born with these long gaps in their esophagus each year.

Typically, treatment involves closing the gap with a piece of the stomach or intestines – which brings the possibility of rejection – or stretching the esophagus by pulling the two ends together. That procedure requires a long hospital stay, Finck said, and can possibly be painful for the babies.

“Here’s this poor kid in the ICU who’s getting their esophagus stretched,” said Finck, who is surgeon-in-chief at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. “It’s kind of a morbid type of procedure. I just felt that there should be a better way.”

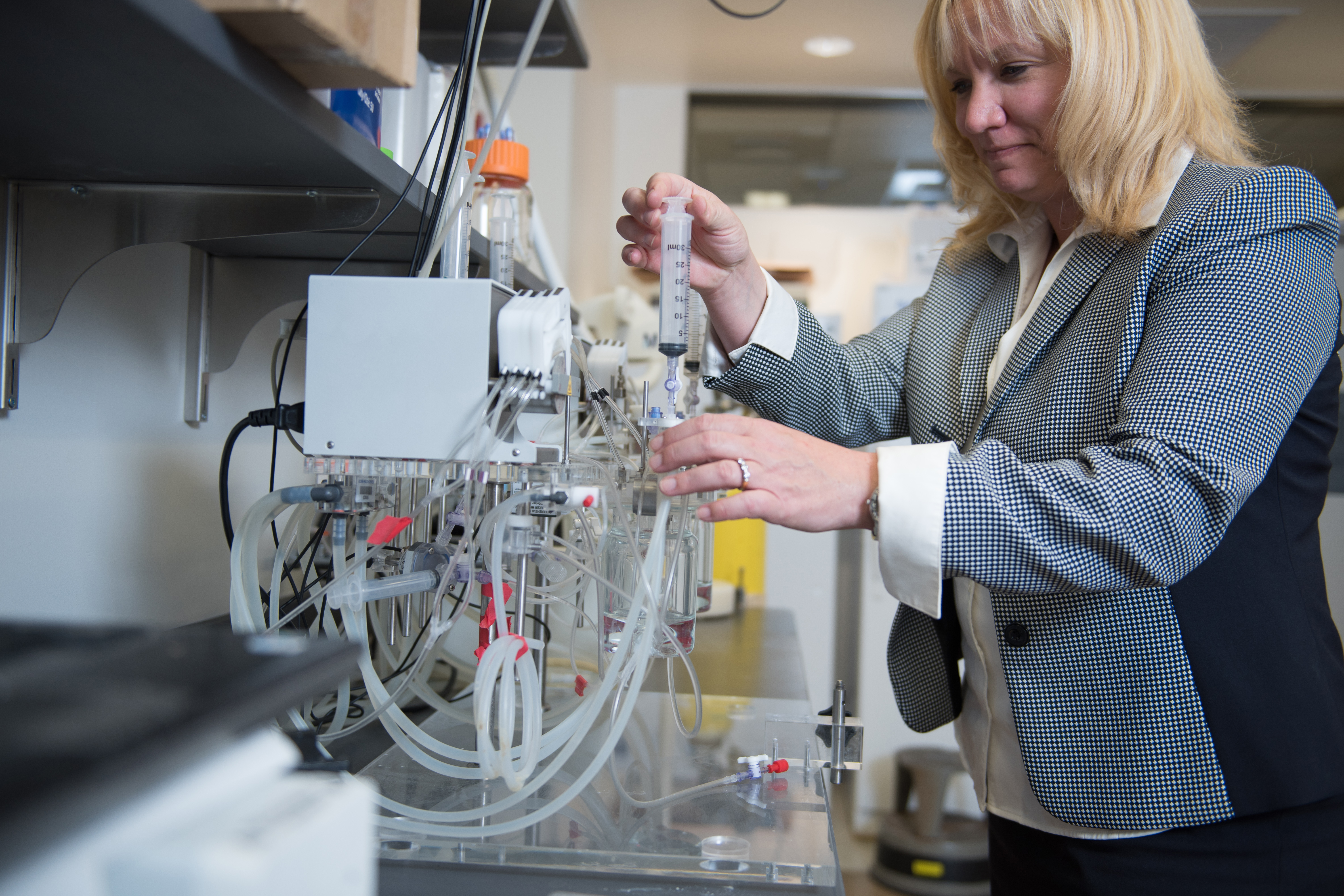

As an associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at UConn Health, Finck and a team of researchers are working hard to find that way, using tissue engineering to develop new methods for treating the condition, which affects one in 4,500 babies.

Finck has partnered with Biostage, a biotech company that has developed a polyurethane tube known as a scaffold that can be seeded with a baby’s own cells. The scaffold is then implanted as a placeholder to bridge the gap in the esophagus. Over time, the esophagus begins to grow around the scaffold, Finck explained.

“After about three weeks, we take out the scaffold and let the rest of the esophagus regenerate,” said Finck. The scaffold is then replaced with a stent to keep the esophagus open. When removed, “a fully regenerated esophagus is left behind,” she said.

Cells for the procedure can be taken from biopsies of the esophagus, from stem cells in amniotic fluid, or from bone marrow. Her team is currently examining which cells produce the best outcome. The procedure can also be used for adults with esophageal cancer or kids whose esophagus is burned after ingesting lye or other caustic substances.

Finck said clinical results in animal models have been successful. “We can do gaps of about 10 centimeters now, which is novel,” said Finck, whose research also focuses on lung disease in premature infants. She expects the procedure will be available for patients in about five years.

A native of Long Island, Finck earned her bachelor’s in biology from Boston University in 1990 and her medical degree from the State University of New York Health Science Center in Syracuse in 1994. She did her fellowship in pediatric surgery at Arkansas Children’s Hospital, and spent five years at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia before joining Children’s, where she has high praise for her team.

“Having a team that works and shares your vision is the best,” she said. “That’s when you get things accomplished.”

Growing up, Finck always wanted to be a doctor and loved taking care of children, a trait she inherited from her schoolteacher mom. She said she fell in love with pediatric surgery “the minute I did it,” and enjoys building relationships with patients’ families.

Reflecting on her career, Finck said two unexpected life events profoundly influenced her. “My first husband passed away from a brain tumor when I was in fellowship,” she said. “That gave me a true vision of being on the other side – of being at the mercy of hospital care.”

Years later, while working in Philadelphia and remarried to her current husband, she adopted her daughter Isabelle, one of her tiny patients.

Isabelle, now 11 and healthy, was born with her intestines outside her body, a condition that required multiple surgeries. Her mother, a teenager with no family support, had confided in Finck that she wasn’t able to care for the infant.

“It just came out of my mouth: ‘I’ll take her,'” Finck recalled. “I remember she turned all red and said, ‘That would be wonderful because you know her best.'”

Finck, who also has two biological children, 8 and 5, said her experience parenting an infant with a complex medical condition continues to drive her research, and helps her empathize with her patients’ families.

“She’s one of the most compassionate and dedicated people I’ve ever met,” said Shefali Thaker, a postdoctoral fellow working as a research associate in Finck’s lab. “She will push and strive to see that all of the children she interacts with are comfortable, and that their families are comfortable. She goes above and beyond every single time.”

Post doc and research associate Todd Jensen called Finck a wonderful mentor to new physicians beginning their research. “She’s supportive and helps them find their niche,” he said.