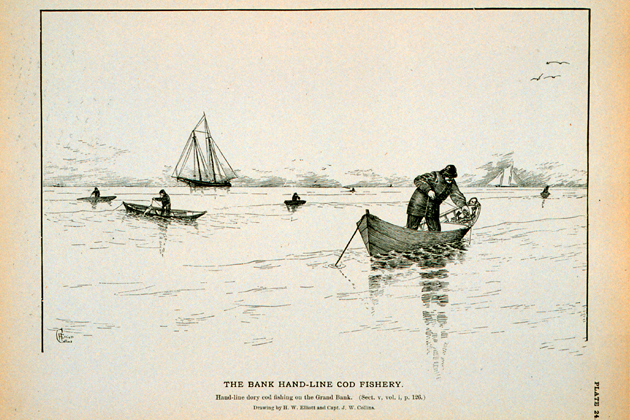

An iconic image of Old Cape Cod is of the solitary halibut fisherman rowing to shore in a dory, Sou’wester pulled low. Winslow Homer’s The Fog Warning comes to mind.

It’s a romantic image, perhaps reflecting human yearning for what people wanted the Cape to be, not what it was, says Matthew McKenzie, assistant professor of history, whose research is examining the complex relationships between humans, the sea, and the resource that once was required for survival on the Cape – fish.

McKenzie studies how changes in the cultural landscape of Cape Cod are linked to the economic and ecological changes just offshore, as fishermen tried to cope with the surge and ebb of consumer demand and a dwindling catch.

His recent book, Clearing the Coastline: The 19th Century Ecological and Cultural Transformation of Cape Cod (University Press of New England, 2010), shows how the spin of Cape Cod’s image as a tourist destination has hidden the Cape’s real story.

That story is more complex. The Cape lost a third of its population between 1860 and 1890, as stocks of herring declined. Property prices and the economy collapsed. By 1890, the Cape had emptied out so much that Massachusetts legislators considered populating it with poorhouses.

Instead, tourists began coming to the Cape after the Civil War, buying up the cheap property. They wanted to see a pristine, natural environment, not the industrial grit of the Cape’s commercial fishing industry, which was responding to their demand for fish, says McKenzie.

But the industrial reality was there, even if they chose not to see it. Of the 506 fishing schooners working out of nearby Gloucester, Mass., in 1870, 409 were owned by 52 large fishing operations. That left a slim catch for the hook-and-line fisherman who worked close to shore. Even then, factory fishing was becoming unsustainable, however. McKenzie says that the romanticized view of the solitary fisherman in his dory, so much a part of the tourist lore, actually helped mask fishing’s decline.

This “history of denial” allowed the exploitation of the fish, a natural resource, he says. Warnings about the drop-off in catch were ignored as fishermen struggled to meet the consumer demand for their product. Yet consumers didn’t want to know how fish got to their plates – through large-scale, commercial overfishing. When stocks declined, fishermen were blamed.

“We celebrate fishermen; at the same time, we condemn them,” he says.

The story is more complex than just overfishing, however. McKenzie is uncovering it by examining records of the U.S. Fish Commission, state biologist reports, the industrial census, historical society papers, and travel descriptions of the Cape in the 1800s. The early Puritan settlers of the Cape valued written records, providing more material.

There is also tourist propaganda about the Cape from the late 1800s and the romanticized narratives of writers such as Henry David Thoreau in the 1850s and author Henry Beston (The Outermost House) in the 1920s. Thoreau eventually confronted the human cost of fishing, McKenzie says, when he met locals who told him about their losses in a terrible 1841 storm, which killed more than 57 fishermen from Truro alone.

McKenzie, who grew up in Falmouth and Woods Hole, is familiar with the local viewpoint. Last summer he worked a weir (trap) with one of the few fishing families left on the Cape. While weir fishermen working near the shore are strictly regulated these days, there are still 200-foot trawlers out on the Georges Bank. An amendment to the New England Fishery Management Plan that would curb mid-level trawling is the subject of current debate, with offshore and inshore fishing interests staking their claims.

Would the disappearance of fishing on Cape Cod matter? Culturally, it does, McKenzie maintains: It would be like losing small farms.

“The identity of the place is so tied up with maritime labor,” he says.

Fish were a critical part of the web of life on the Cape before 1830, providing not only food but also fertilizer for farming, he says. The herring catch was so important to survival that it was carefully regulated by town meetings. Then settlers found a source of income in auctioning off herring runs to the highest bidders. Within 50 to 75 years, a lot of these runs were exhausted, or herring became bait for Grand Banks fishermen, McKenzie says.

This had far-reaching consequences and resulted, in 1871, in a political rally on Beacon Hill by 3,000 inshore fishermen, mad that their stocks had declined.

The collapse of the fishing industry in Cape Cod has led to a growing but hidden poverty there, McKenzie contends. Tourism provides low-paying service jobs, not the working- or middle-class living that fishing once provided. The retirement population keeps a small home-building and landscaping industry going for the time being.

“We haven’t seen how badly we’ve managed our marine resources until the last 20 years,” he says. “We sequestered maritime history for a long time.”

Hear how Matt McKenzie became interested in this research topic.