The UConn Reads Student Essay Contest is new this year. It was suggested by President Herbst, and her office has generously sponsored the prizes. The essay contest provided another avenue for student involvement in UConn Reads, one that could be connected to a class or pursued independently.

This year’s contest posed a seemingly simple question: what makes Gatsby your classic? Students could choose their own approach or focus on some of the key aspects of the American experience addressed in the book, such as conflicts of class and culture; the nature of the American dream and its price; the complexities of romantic love and marriage; truthfulness, fidelity, and cheating in their many forms; American regionalism.

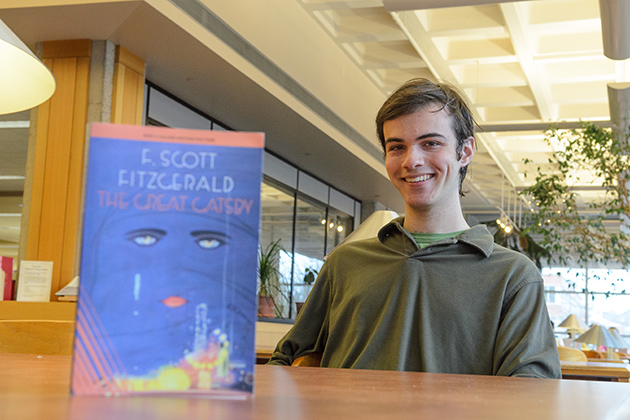

The faculty committee was impressed by the way that the winning essay, by journalism major Jesse Rifkin, connects the book’s reflections on the American dream with his own family history, specifically with the way that his family potentially viewed his decision to major in journalism as derailing their multi-generational pursuit of the American dream.

Anne D’Alleva, chair of UConn Reads 2012-13

Joseph Rifkin, Journalism, and Gatsby’s American Dream

Joseph Rifkin lived in Minsk, Russia as a cantor before moving to Paterson, New Jersey. Joseph’s oldest son Samuel Rifkin became a candy store owner. Samuel’s oldest son William Rifkin became an accountant. Samuel’s oldest son Lawrence Rifkin became a pediatrician. Lawrence’s oldest son is me.

So in my mind, the American Dream is not as elusive as F. Scott Fitzgerald paints it in The Great Gatsby. True, the dream is usually not necessarily captured immediately, or often even within one’s lifetime. But through the building of solid foundations, almost anything can eventually become achievable. One cannot reach the ladder’s top rung unless there is a bottom rung to begin with.

Which is precisely why my father expressed such initial hesitation towards my decision to enroll at the University of Connecticut as a journalism major. Our genealogical records do not go back before the 1800s, but more than likely his ancestors when living in Eastern Europe had worked as butchers, bakers, and similar jobs for hundreds of years. Never changing, never advancing. As Dad saw it, his life was the product of a uniquely American ideal, one he felt compelled to carry forth into successive generations reaching ever-greater heights. To him, my entering journalism marked the first downward slip in that century-long elevation.

As Fitzgerald wrote of Jay Gatsby, “He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.” Did Dad feel the same way?

During my freshman year, I took my first journalism course: “The Press in America” taught by Timothy Kenny. Learning about the history of journalism taught me that the field was filled with people who had achieved the American Dream. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered President Richard Nixon’s illegal Watergate wrongdoings, leading to an unprecedented presidential resignation as well as a series of campaign finance reforms. Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose works in the North Star newspaper and the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (books are a form of the press, too) collectively persuaded millions to see the moral unrighteousness of slavery. Not to mention the Founding Fathers who drafted the first constitution in the world which enshrined freedom of the press as a constitutional right – arguably, those Founders could be considered the very first people to achieve the American Dream.

But would it be possible for me to achieve the American Dream? The odds seemed unlikely. For the first time, polls and surveys were demonstrating that less than half of respondents felt the dream was still possible today. Young people, generally considered the most idealistic, were supplying among the highest rate of “no” answers. Not to mention the contemporary newspaper layoffs and worst-since-the-Great-Depression economy. Fitzgerald had written (from the perspective of narrator Nick Carraway) that “After two years I remember the rest of that day, and that night and the next day, only as an endless drill of police and photographers and newspaper men in and out of Gatsby’s front door.” That was in 1925. Today, would those outside Gatsby’s front door instead have been bloggers and correspondents for Entertainment Tonight?

Undaunted, I persisted. And a funny thing happened along the way: no small thanks to my professors and experience at UConn, I achieved. My article “What Generation Gap?” was published in the Sunday Chicago Tribune in February of my freshman year. Another piece entitled “Listening to Every #1 Song Ever” was published in the Sunday Washington Post that April. Sophomore year I was named College Columnist of the Year by the National Society of Newspaper Columnists, and they flew me down for free to accept the award at their annual conference in Atlanta. That summer I earned an internship at the Hartford Courant, the largest newspaper in the state. This upcoming summer I earned an internship at USA Today, the second-largest newspaper in the country.

Dad slowly began revising his opinion of my journalism major.

And it was not just the academic or writing techniques I learned in my journalism courses. In the final minute of the final day of the final class in “The Press in America,” Professor Kenny said, “I want to leave all of you with some advice.” I waited. “It is the best advice I can possibly give you.” I waited. “Never forget this.” I waited. “Are you ready to hear it?” YES ALREADY! I wanted to scream.

Professor Kenny looked around the room and stated rather simply, “Do the right thing. Class dismissed.”

My jaw almost dropped. Do not necessarily do the easiest thing. Do not necessarily do the most popular thing. Do not necessarily do the most fun thing. Acting according to all three of those value systems inadvertently destroyed the lives of most of the main characters in The Great Gatsby. Do the right thing. Kenny’s words have stayed with me ever since.

Unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald – or, if the current polls are to be believed, most current Americans – I do not believe achieving the American Dream is dead. I do believe that it is more difficult than in some previous eras. But then again, it was never easy to begin with. Even among those who have managed to achieve it, sustaining it proves equally hard, if not harder. According to Perry Cochell and Rodney Zeeb in their book “Beating the Midas Curse,” on average 65% of family wealth is lost by the second generation and 90% by the third generation, while 70% of businesses fail to make it to generation two and an astounding 97% fail to make profits by generation three.

Fitzgerald begins The Great Gatsby this way: “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” Joseph Rifkin’s true mark resides not so much in anything he did, but in what Samuel, William, and Lawrence did. If all goes according to plan and my next thirty years mirror my past three, add me to that list as well. In a world in which most people on our planet still find the notion of advancing themselves or their children impossible due to political or economic realities of their society or nation, that is truly the American Dream.