Assistant professor of geography and geosciences William Ouimet and Ph.D. student Katharine Johnson have successfully combined state-of-the-art remote sensing technology with their mutual appreciation of New England’s rich and varied history to uncover long-lost features beneath the forest canopy that covers the region.

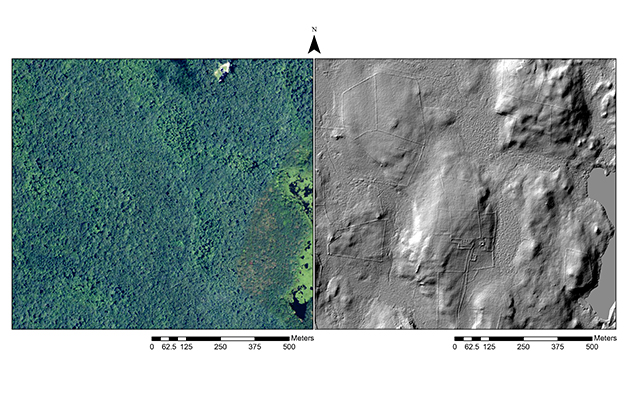

As part of their research into the cultural, climatic, and geological transformation of the region over time, Ouimet and Johnson have gathered images of the towns of Ashford, Conn., Westport, Mass., and Tiverton, RI, that were taken by airborne light detection and ranging (LiDAR) laser-based scanners. The scanners provide high-resolution, three-dimensional images of topographic and archaeological features that are hidden by the forest, such as stone walls, building foundations, mill dams, and abandoned roads and pathways.

Modern laser-based remote sensing dates from the 1970s, starting with efforts by NASA for atmospheric research and meteorology. With the addition of Global Positioning Systems (GPS) in the 1980s that allowed for precise positioning of aircraft, the resolution and quality of LiDAR has improved through the years, and now the technology is regularly utilized by geologists, archaeologists, and other scientists who need detailed topographic information. The quality of currently available images has given researchers such as Ouimet and Johnson access to a trove of information that had previously been difficult, if not impossible, to access.

Data sources: CTECO (imagery) and USDA NRCS (LiDAR)

“Even though we think of New England as being densely populated, there is a lot of forested land for which detailed maps don’t exist,” Ouimet says. “Roads and population centers have shifted and previously occupied land has long been abandoned. It would take an enormous amount of time if we had to go out into these forests and map the land ourselves. Using LiDAR is like surveying on steroids – you can see so much detail immediately, including features as small as two or three feet across.”

The information they are gathering will help Ouimet and Johnson reconstruct the paths and patterns of early European settlers.

Johnson says the LiDAR images enable her to understand the layout of long-abandoned farmsteads, and to examine the placement of stone walls and their relationship to the landscape.

“Presumably, people made conscious choices about where to put houses and outbuildings, and they decided what acreage to clear for fields and where they wanted to put up [stone] walls,” she says. “Being able to uncover hidden landmarks has the potential to give us a much greater understanding of what transpired hundreds of years ago.”

Ouimet says that LiDAR technology has been used elsewhere to explore historic sites, including Stonehenge in England and Ciudad Blanca, a suspected, yet previously unconfirmed, metropolis hidden in the Honduran rain forest. But, he emphasizes, we shouldn’t overlook what’s in our own back yard.

“I have a passion for understanding how the earth works, and that includes how the physical appearance of land has been shaped by humans,” he says, noting that New Englanders sometimes take for granted the surrounding landscape and landforms, including the network of stone walls that crisscross the region.

“With this technology, we are seeing things we didn’t know were there,” Ouimet says. “We can begin to quantify the patterns of land modification and the amount of stone that was actually moved to make these farmsteads. It was an enormous undertaking. This project thus allows us to explore and appreciate the local environment from an interdisciplinary perspective – emphasizing the cultural, geological, and historical narratives at play.”

In a paper in the March 2014 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, “Rediscovering the lost archaeological landscape of southern New England using airborne light detection and ranging (LiDAR)” the researchers say their findings will enable them to quantify the historical human impact on the landscape by studying details at a much higher resolution than has been previously available.

And to this, Johnson adds, “The more we discover the more questions we have, and that is what makes this work so interesting.” She cites an instance in which they correlated what they could see in the LiDAR images of Westport, Mass. with a map dating from 1712. By geo-referencing the map and digitizing the stone walls, they could see that the property boundaries created more than 300 years ago match many current property lines today.

“So a question is, ‘What was the decision-making process of the people who created the boundaries in the first place that has made them stand the test of time, and how have those boundaries impacted the landscape up to the present?’

“I’m looking for the answers,” she says, “one image at a time.”