In 1654, a group of 23 displaced Jews, who had left a Brazilian government inhospitable to the Jewish people, arrived by steam ship at the port in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, looking for a new place to call home.

The colony’s skeptical governor wrote to his government back home, asking what to do with the immigrants. If I accept these Jews, he complained, I’ll have to start receiving other non-Protestants, like Catholics. But the response came back firmly: Keep the Jews, the Dutch East India Company said, they’ll be productive citizens.

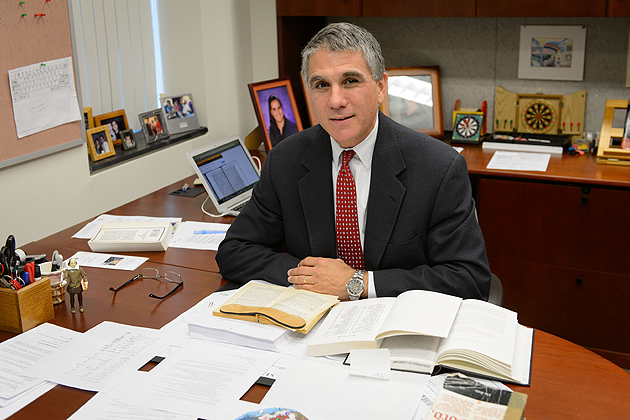

Thus the first official census of Jewish people in the United States was recorded, says Arnold Dashefsky, professor emeritus of sociology and former director of UConn’s Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life.

Since then, those immigrants have given way to a current estimate of 6.8 million Jews in the U.S., as reported by Dashefsky and his colleagues in the 2015 American Jewish Year Book, set to be published in November. And the definition of Judaism – what it actually means to be Jewish – has changed quite a bit, too.

“At this time of year, rabbis say this a lot, but it’s true: Judaism is more than a religion,” says Dashefsky.

His work, and that of the UConn Center for Judaic Studies, continues to define what it means to be Jewish: not just by religion, but by heritage, culture, and community; and not just in modern times, but in the distant past and the future.

One way that UConn is continuing to define what it means to be Jewish is through community conversations. Eight Judaic Studies professors are on the roster to lead discussions at Connecticut synagogues, community centers, and libraries over the next nine months.

Faculty will be leading talks on more than 25 topics, such as Israeli-Arab relations and the use of military force, new perspectives on Holocaust perpetrators, and the idea of forgiveness as represented in the works of Shakespeare. Political science professor Jeremy Pressman, an expert in Middle East Studies, is slated to discuss the pending Iran nuclear deal in detail.

In its 36 years, the Center has evolved from a pair of faculty members teaching a handful of courses to a thriving center with four full-time Judaic studies faculty and 26 affiliated faculty.

What has distinguished the Center from other Judaic studies programs across the country, says Jeffrey Shoulson, the Center’s director, is its expertise in early Jewish periods, including representations of Judaism in literature and culture in the pre-modern era.

Shoulson, who holds the Doris and Simon Konover Chair in Judaic Studies, has given two talks so far, and says they’ve been invigorating.

“People come with questions about Judaism that they’ve just been dying to ask someone,” says Shoulson. “It’s great to be able to have those kinds of frank discussions. Humanists have a duty to remind people of the importance of what we do, and this is one way to show people how our work matters.”

In an age where establishments of all kinds are eschewed in growing numbers by the public, the idea of formalized religion is becoming less popular, says Dashefsky. He notes, however, that unlike other religions that rely exclusively on a belief in God or another higher power as the criterion for membership, Judaism also defines itself ethnically or culturally.

“As sociologists, we define a Jewish person as one who identifies him or herself as Jewish,” says Dashefsky. It’s even possible to identify as both an atheist and a Jew, he adds.

Shoulson also stresses that, like the myriad Judaic studies courses at UConn, the community discussions – fondly referred to as the “Judaic Studies Road Show” – is certainly not just for Jews.

“We’re definitely not promoting a particular religious point of view,” he says. “We’re engaged in an academic study of the Jewish culture, and our classes and talks reflect that.”