Before long, the sounds of chain saws and large land clearing equipment will echo over a portion of UConn’s northwest corner. By summer, the now wooded acres, adjacent to the University’s Spring Manor Farm on Route 32 and near the UConn compost facility, will begin their transition back to agricultural production.

Mary Kegler, manager of farm services, views the upcoming transformation as a positive move for the College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources. Jennifer Kaufman, natural resources and sustainability coordinator for the Town of Mansfield and staff liaison to Mansfield’s Agriculture Committee, agrees that it’s the right move for the town.

But why the change?

This activity is the result of farmland mitigation – a way to assure that the total amount of land once dedicated to agricultural use in a community is not forever lost when farm parcels are converted to a different use.

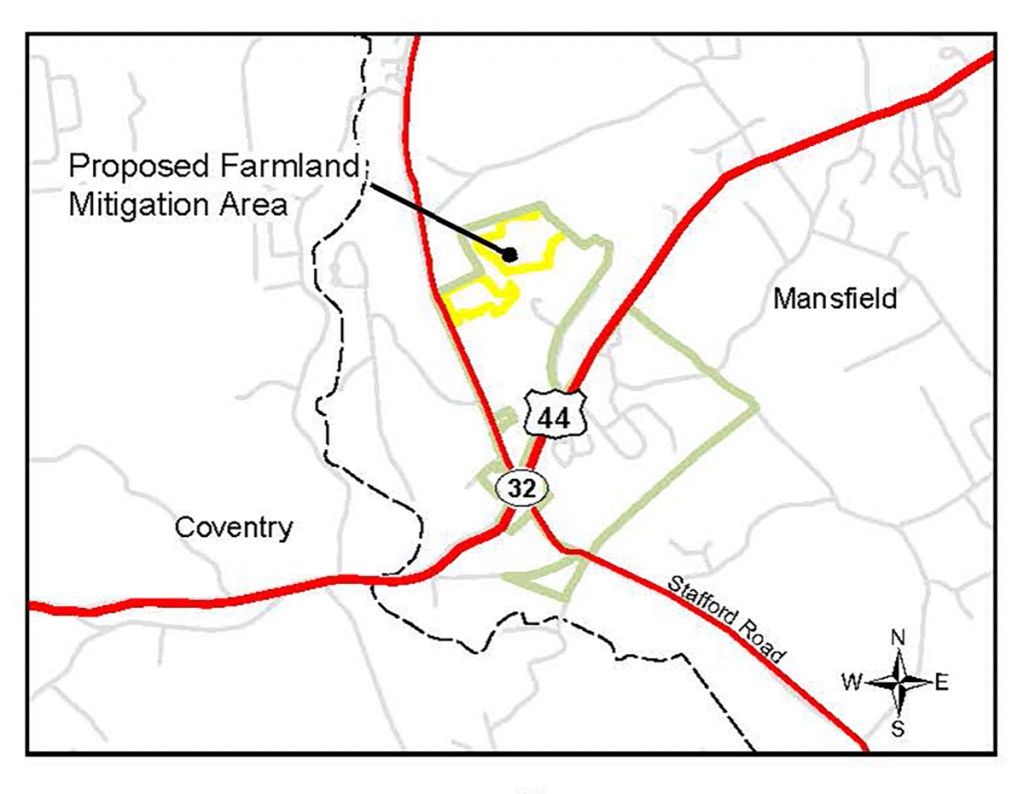

In this case, the requirements for mitigation were contained in the environmental impact studies done for the construction of the Charter Oak Apartments and the extension of North Hillside Road – now named Discovery Drive – which resulted in the loss of approximately 35 acres of cultivated farmland on UConn’s North Campus.

Rich Miller, director of UConn’s Office of Environmental Policy which is responsible for ensuring that the University honors its environmental commitments, says he and his staff have been coordinating aspects of this farmland mitigation effort for more than 10 years and the intent has always been to replace those lost agricultural acres. The only question was where the land would come from.

Working with the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service, UConn ultimately selected nearly 40 acres of University property that is now wooded but was once farmland known as Rock Spring Farm. The parcel selected intentionally exceeds the 35 acres of agricultural land that have been lost, as a margin of safety in case the project encounters sections of land that cannot be disturbed due to the presence of wetland soils or rock outcrops.

Kegler says, “You can see evidence of how the land was used in the past by looking at the remains of an old dirt road around the perimeter, as well as wire fencing and stone walls that still intersect the property. The trees are all about the same age, roughly 60 years old, so we know that the land was once cleared and used for farming.”

She says that the additional farmland will have a variety of positive effects, and will be especially welcome because it will give the University more land for crop rotation – an important soil conservation management practice. She explains that well-drained, tillable flat land is used to grow corn, and with this additional open land Farm Services will be able to put in a corn crop while other areas are rested by planting clover and other cover crops, including both legumes and grasses. This rotation helps keep the soil healthy and productive.

Kegler says UConn’s award-winning dairy herd will be a beneficiary of the increased farmland. She says the University grows corn for silage – a kind of fermented cereal for cows – and may also be able to grow additional hay for the herd, perhaps with alfalfa, on the new agricultural land, representing a financial savings to the Farm Services’ budget.

But the benefit is not just to UConn.

When the long-planned-for connection from campus to Route 44 – Discovery Drive – opened in December, more than a few members of the Mansfield community reacted with a huge sigh of relief, including Kaufman, the town’s sustainability coordinator.

“From the perspective of the town, we can already see that the new road is helping alleviate traffic congestion on Route 195,” she says, “and we’re grateful for that.

“While keeping a natural system intact is always the optimal approach, sometime tradeoffs must be made,” she adds. “We appreciate that UConn is fulfilling its obligation by returning this land to productive farmland, and is working with the Natural Resources Conservation Service to implement good land management practices. This is in keeping with our goal of preserving Mansfield’s rural character.”

Miller, UConn’s environmental policy director, notes that returning the land to agricultural production is an important step in maintaining the University’s land-grant heritage.

“It’s great when we can advance projects like this,” he says, “to help preserve natural history and restore land uses that are so important to the fabric of the community. It’s one of the best parts of my job.”