When the creators of the hugely popular podcast “Crimetown” decided to make Providence the focus of their first season, it didn’t take long for them to come knocking on Mike Stanton’s door.

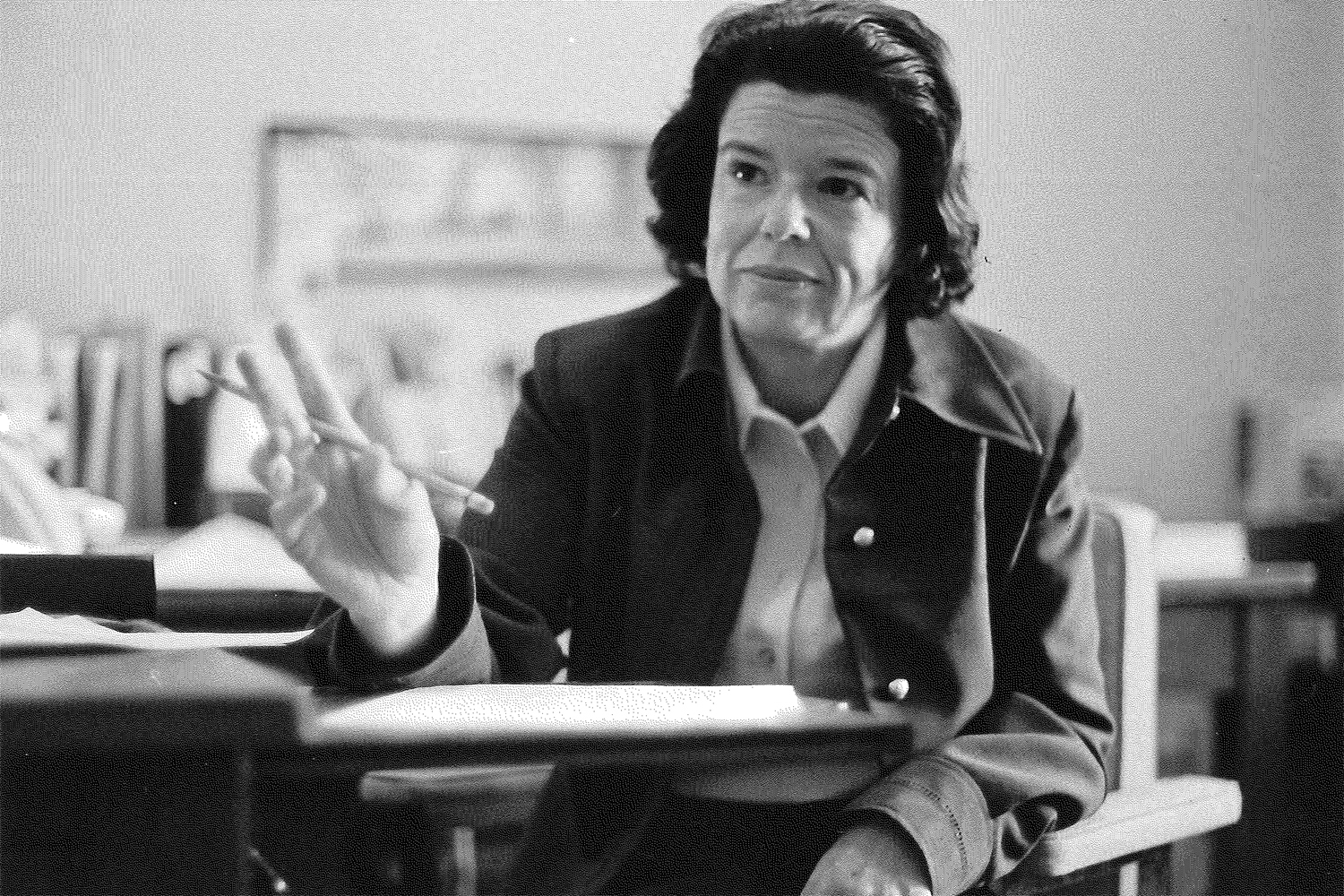

The UConn journalism professor is a well-recognized expert on crime in Rhode Island’s capital city, having worked for more than two decades as an investigative reporter at the Providence Journal before joining the UConn faculty in 2013. During that time, he broke stories about mobsters, crooked politicians, and systemic corruption in the state Supreme Court. In 1994, he shared a Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting on the latter story. Stanton also covered the corruption trial of Providence Mayor Vincent “Buddy” Cianci and wrote a best-selling book about him.

Fresh from a recent trip to the show’s Brooklyn studio to narrate the 17th episode of “Crimetown,” Stanton shared his excitement about being part of the series and the new model of journalism that it represents. The final episode, on May 7, marks the end of a more than two-year collaboration with podcast producers Marc Smerling and Zac Stuart-Pontier, two writers-turned-filmmakers who, after winning an Emmy for their hit HBO series “The Jinx,” decided to focus on sound.

Stanton brought the two to campus last year to speak with his students along with another character in the podcast, Charles “The Ghost” Kennedy, a big-time drug trafficker who, while serving 14 years in prison, became a source of Stanton’s, writing and calling him from jail.

“During that visit Marc talked about the purity of sound and telling stories through the radio and the new model of delivering them through podcasts,” says Stanton. “As the younger generation has cut the cord to traditional media, podcast listenership has really soared.”

“Hopefully it creates some excitement about journalism, and shows that the reports of its demise are greatly exaggerated.” — Michael Stanton, associate professor

With 16 million downloads to date, “Crimetown” is proof of that. The series was named one of the top 10 new podcasts of 2016 by the New York Times.

Smerling already had a fascination with Providence when he decided to make the city the focus of the first season. He spent a lot of time there during college visiting with his now former wife’s family. The daughter of a fellow producer put him in touch with Stanton and the late Bill Malinowski, his longtime partner and fellow investigative reporter at the Providence Journal.

Smerling had been following the career of Buddy Cianci since his former father-in-law introduced them. As his research deepened, he became fascinated by the commingled cultures of crime and politics in Providence. That, in turn, took him deeper into Buddy Cianci’s story, says Stanton.

“Of course, I know a lot about that because I wrote the book about him and I covered his corruption trial for the Providence Journal, so we started talking a lot more,” he says.

Stanton and Malinowski, who was working on a book about Charles Kennedy at the time, introduced Smerling and Stuart-Pontier to their sources in law enforcement and the mob. Malinowski, who had been diagnosed with ALS, would meet with Stanton and the two producers to talk about what they were working on, offering input, advice and information, at times joined by former cops and wise guys.

“It was nice,” says Stanton. “It kind of kept Bill going.”

Stanton and Malinowski, who died last summer, were interviewed twice for the different episodes of the podcast. The “Crimetown” website is rich with photographs culled from the archives of the Providence Journal, the city of Providence, and the Rhode Island Historical Society. Smerling and Stuart-Pontier also weave all sorts of audio artifacts into the podcast, including tapes of live radio and television broadcasts and the FBI wiretaps played at Cianci’s corruption trial.

During his visit to Stanton’s class last spring, Smerling played a segment of “Crimetown” for students. It combined the historic audio files and sound effects that he and Stuart-Pontier created.

“In some ways it harks back to the early days of radio and the Lone Ranger when you had the clip clop of horses’ hooves made by cups in the studio,” Stanton says. “With a podcast, it’s very subtle and fact-based, like the story of a mob heist when they make the sound of the blowtorch they are using to open the safe, or when the mob guy is taking somebody for a ride and you hear the sound of the car door.”

Stanton is intrigued by the way podcasts are pushing the boundaries of journalistic storytelling to create a new art form. “Crimetown” and its production company, Gimlet Media, exemplify the changing face of media and, while their approach to telling stories is new, the fundamentals of good old-fashioned storytelling still apply.

“So it’s not only teaching kids the traditional basics of original documents, like a state police arrest warrant affidavit, but all the other elements that Marc and Zac are using to create context,” Stanton says. “I hope it gives students a real-life illustration of the kinds of things they can do. I hope it gets them jazzed up and excited and shows them the path forward that they are going to help invent. Hopefully it creates some excitement about journalism, and shows that the reports of its demise are greatly exaggerated.”