Each year, as many as 25,000 people are maimed or killed by landmines around the world, including large numbers of civilians.

While landmines are inexpensive to produce – about $3-$30 each, depending on the model – finding and clearing them can cost as much as $1,000 per mine. It is a slow and deliberative process. Specially trained dogs are the gold standard, but they can be distracted by larger mine fields and eventually tire. Metal detectors are good, but they are often too sensitive, causing lengthy and expensive delays for the removal of an object that may turn out to be merely a buried tin can.

A UConn chemical engineering doctoral student hopes to help. Ying Wang, working in conjunction with her advisor, associate professor Yu Lei, has developed a prototype portable sensing system that can be used to detect hidden explosives like landmines accurately, efficiently, and at little cost.

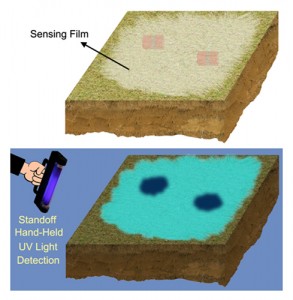

The key to the sensing system is an advanced chemically-treated film that, when applied to the ground and viewed under ultraviolet light, can detect even the slightest traces of explosive chemical vapor. If there is no explosive, the film retains a bright fluorescent color. If a landmine or other explosive device is present, a dark circle identifying the threat forms within minutes.

One of the world’s top private landmine clearing companies, located in South Sudan, is currently working with Lei and Wang in arranging a large-scale field test. The results of the field test could be of interest to the United Nations, which has worked to make war zones plagued by old landmines safer through its United Nations Mine Action Service. It is estimated that there are about 110 million active landmines lurking underground in 64 countries across the globe. The mines not only threaten people’s lives, they can paralyze communities by limiting the use of land for farming and roads for trade.

“Our initial results have been very promising,” says Wang, who receives her UConn Ph.D. May 5. “If the field test goes well, that is a real world application. I’m very excited about it.”

Doing work that has real world applications and that will help improve people’s lives is an important part of what drives Wang in her research.

“When I started working with landmines, I was thrilled,” says Wang, who received her bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Xiamen University in China in 2004 and her master’s degree in biochemical engineering from Xiamen University in 2007. “I knew this would be a really good application of our work. It can save lives.”

Wang and Lei are currently working with UConn’s Center for Science and Technology Commercialization (CSTC) in obtaining a U.S. patent for their explosive detection systems.

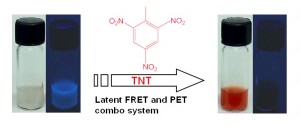

Besides the sensing method for explosives vapor, the pair has also developed a novel test for detecting TNT and other explosives in water. They recently presented their results at the 243rd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS) in San Diego, Calif. That research is also the subject of a U.S. provisional patent.

The latter application can be used to detect potential groundwater contamination in areas where explosives were used in construction. It can also be used in airports to help thwart possible terrorist threats.

Most airlines currently limit passengers to about 3 ounces of liquids or gels when boarding a plane because of the potential threat of carry-on explosives. That may change if Wang and Lei’s new sensing system is adopted. The pair have developed an ultrasensitive real-time sensor system that quickly detects both minute and large amounts of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene or TNT. When searching for trace amounts of explosives, a paper test strip with the sensing chemicals on it can be dipped into liquid samples to test for small molecules of explosive. Wang and Lei’s sensor can detect TNT concentrations ranging from about 33 parts per trillion (the equivalent of one drop in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools) to 225 parts per million.

“Our new sensor based on a recently developed fluorescent polymer for explosives in aqueous samples has two sensing mechanisms in one sensing material, which is very unique,” says Lei. “The sensor can easily be incorporated into a paper test strip similar to those used for pregnancy tests, which means it can be produced and used at a very low cost.”

Wang has authored 17 papers, two patents, and one book chapter during her time at UConn and her research has been supported by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Homeland Security.