[yframe url=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KzerHULhZ64&feature=youtu.be’]

Since it opened in the Neag School of Education two and a half years ago, UConn’s Korey Stringer Institute has been on a mission to protect high school athletes around the country from heat stroke and other serious illness and injury.

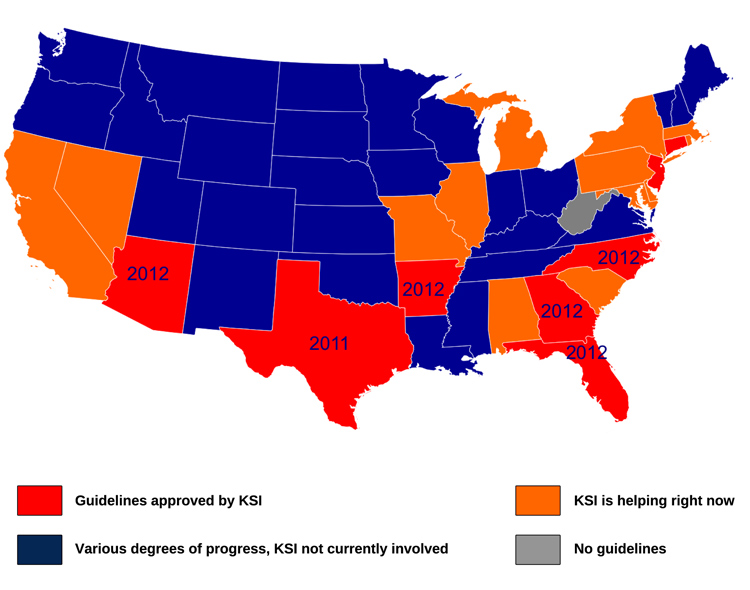

To date, eight states – Texas, Georgia, Arkansas, Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, New Jersey, and Connecticut – have adopted important pre-season practice guidelines promoted by the Institute. The guidelines eliminate intense “two-a-day” workouts at the start of preseason, and allow young athletes’ bodies to gradually adjust to exertion in hot weather during phased-in summer practices.

Fourteen others states are currently working with the KSI to improve their existing policies so they are in line with the Institute’s recommendations.

UConn kinesiology professor Douglas J. Casa, the Institute’s chief operating officer, says the KSI’s goal is to have every state in the country adopt the guidelines within the next few years.

“The majority of heat stroke cases occur during initial summer workouts when athletes are neither prepared to cope with the environmental conditions nor the new physiological demands placed on them during workouts,” says Casa. “These heat acclimatization guidelines mandate that athletes be eased into these intense practice sessions, lowering their chances for exertional heat stroke.”

According to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, heat illness is the leading cause of death and disability among high school athletes in the United States, sidelining athletes for more than 9,000 days a year, with most instances occurring in August when intense pre-season practices start. Since 2006, there have been 20 heat stroke-related deaths of high school athletes, according to the University of North Carolina’s National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury. A 2012 study by researchers at the University of Georgia revealed that deaths of high school football players due to heat nearly tripled from 1994 and 2009 compared to the previous 15 years.

Named after the Minnesota Vikings offensive lineman who died from exertional heat stroke in 2001, the Korey Stringer Institute is dedicated to providing first-rate information, resources, assistance, and advocacy for the prevention of sudden death in sport. Heat stroke is one of seven core issues the KSI focuses on. The Institute also advocates for greater use of automated external defibrillators; mandated athletic trainers on site for all high school practices and games; expanded coaching education; use of wet bulb globe temperature for more accurate weather readings reflecting heat, humidity, and solar radiation; and the creation of clearly-defined emergency action plans for when athletes fall ill.

Stringer’s widow, Kelci Stringer, created the Institute at UConn because of the University’s national reputation for top-flight research in heat, hydration, and other issues impacting the performance of athletes and the physically active. The Institute is part of UConn’s Neag School of Education and Department of Kinesiology. The National Football League, Gatorade, and TIMEX support the Institute’s work as corporate sponsors.

Working state by state

Casa and staff from the KSI have been traveling around the country over the past two years meeting with coaches, parents, athletic associations, and lawmakers in an attempt to gain support for the heat acclimatization guidelines, which were first introduced through the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) in June 2009. Casa co-chaired the NATA committee overseeing the new standards.

One state was particularly aggressive about adopting the new guidelines. After three young athletes collapsed from exertional heat stroke in 2010 during one of the hottest summers on record, Arkansas officials moved swiftly to put greater protections in place.

One of the athletes, a 16-year-old high school football player named Tyler Davenport, died from complications due to exertional heat stroke. Two others, high school football player Will James and junior high basketball tryout Logan Johnson, survived, primarily due to quick-thinking staff members who moved swiftly to cool the boys’ bodies prior to transport to a local hospital.

Nine months after the incidents, Arkansas officials adopted new laws requiring all public high schools to have emergency action plans for serious athlete illness or injury; automatic external defibrillators on site; and additional emergency medical training for coaching staff. Arkansas adopted NATA’s heat acclimatization guidelines in 2012, and is now considered a national leader in protecting its high school athletes on the practice field.

“I absolutely think these policies were needed,’ says Jason Cates, head athletic trainer at Cabot Public Schools in Arkansas and current president of the Arkansas Athletic Trainers’ Association. “We had three high-profile incidents in the state of Arkansas in 2010. We had no choice but to make changes to how we were managing two-a-day workouts in Arkansas.”

Stricter practice standards

Heat-related incidents were dramatically reduced in college athletics after the NCAA adopted stricter practice standards in 2003. The National Football League eliminated two-a-day contact practices as part of its 2011 collective bargaining agreement with the NFL Players Association. But high school athletics is different, Casa says. There is no overarching national governing body that has the authority to mandate policy changes, and states are left to their own devices in terms of regulating athletic practice sessions. Most states’ policies are conveyed as recommendations, with little or no penalty for non-compliance.

So the struggle, for the Korey Stringer Institute, NATA, and the high school parents and community associations looking for change, centers on the local and state level.

“The body of evidence supporting heat acclimatization is large,” says Casa. “By not mandating heat acclimatization guidelines, states are failing to protect their athletes, and in fact are placing them at greater risk for exertional heat stroke and other heat-related illnesses. We urge coaches, school leadership, parents, and legislators to push their states to establish new guidelines or have inadequate guidelines revised.”

Cates notes that persuading states to change has taken a lot of effort on the part of Casa and his staff.

“Getting those eight states to adopt these rule changes has been a monumental feat,” Cates says. “Change is hard on any level, but the facts have been proven from studies done at KSI, at the NCAA level, and with the recent three-year study in the state of Georgia. We still have a long way to go, but we now have eight states that serve as models.”

Casa says it shouldn’t take an untimely athlete death to draw attention to critical issues like heat stroke and the need for more athletic trainers on site at high school practices to keep students safe. The Korey Stringer Institute is seeking additional financial support so that it can continue conducting research, building a national policy database, and advocating for families and youths across the country.

The Institute has garnered many supporters along the way. Andrea Johnson, Logan Johnson’s mother, is one:

“Our family has been fortunate to meet Dr. Douglas Casa of the Korey Stringer Institute,” she says, “and we hope that through Logan’s story, others will be educated about exertional heat stroke and help spread the word to save many lives.”

Anyone wishing to support the Korey Stringer Institute with a gift that supports its research and work building a national policy database and advocating for families and youths across the country may give online at www.friends.uconn.edu/koreystringerinstitute.