Making new friends didn’t come easily to “Kate.” She kept to herself. She didn’t trust people. But that changed when she came to UConn’s new First Star Academy, a residential summer program for high school students in foster care.

“They’re like family to me now,” the high-school junior from New Haven says of her classmates.

Kate* is one of 19 foster kids from across the state taking part in the program. For four weeks starting on July 7, they have lived on the Storrs campus – forming close bonds, earning college credits, and perhaps most importantly, learning that college is not beyond their reach.

Appalling statistics

College graduation rates for foster kids are “horrifically low,” according to Preston Britner, professor of human development and family studies and a member of the Academy development team. Some studies put the figure at less than 3 percent nationally. Foster children also experience disproportionately higher drop-out rates, homelessness, and other social ills, Britner adds.

Brett Rayford, director of Adolescent and Juvenile Justice Services for the state Department of Children and Families (DCF), says a college education is a “game changer” for many kids who have experienced abuse and neglect. “We believe we’re being good parents by educating our children so they can take care of themselves,” he says. DCF is paying the lion’s share of costs for the First Star program. Substantial additional funding comes from the University, private donors, and corporate support, including a grant from the LEGO Children’s Fund.

First Star prepares students for higher education by giving them a taste of college life in a safe, supportive, and healthy environment. Students live in a dorm, take summer courses, and participate in self-exploratory and recreational activities while working with a network of caring mentors, some of whom are products of the foster-care system themselves.

“Many times school personnel don’t have high expectations of these kids because of their past situation in life,” says program director Susana Ulloa. “Our goal is to show them that they do belong on a college campus.”

Adds vice provost for academic affairs Sally Reis, who was instrumental in getting UConn’s First Star program off the ground: “We want to give a start to kids who, through no fault of their own, have had a rougher road.”

Participants are selected by their DCF social workers, Reis explains. “We’re looking for students in the top 20 percent of their high school class,” she says, “kids with the interest and motivation to go to college.”

‘A breakthrough for a lot of kids’

One of those kids is “Dale,” a high-school freshman from Hartford. He says First Star is helping him move forward in life and express himself emotionally. “It kind of pushes back my past,” he shares. “It’s been a breakthrough for a lot of kids.”

It was for Kate, who says the most important thing the program has taught her is to accept other people. “We’re all the same,” she has learned, “we just have different stories.”

Residence hall director Johanny Baez ’12 (CLAS), who was in DCF care herself until she graduated from UConn, has enjoyed watching the changes in the students. They came in quiet, and afraid to speak or smile, she says. “Now they’re like this,” she says, crossing one finger over the next.

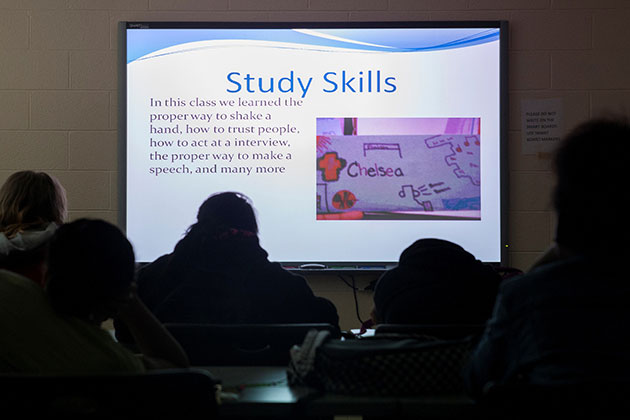

In addition to taking classes in subjects like English, math, and science, the students also learn life skills, including how to prepare for an interview and how to manage time, stress, and money. They go on college visits and weekend field trips to fun places like Golf Land in Vernon. They also get their own video cameras to create a digital journal of their experience.

Students enter the Academy in 9th grade and come back each summer until they graduate and are ready to enter college. Because this is the first year, some of the participants are sophomores and juniors. In addition to the summer component, the program provides regular contact and support during the academic year.

“This could be a big jump start towards college for any kid in DCF,” says “Jayden,” a sophomore honors student from Stamford, who plans to earn nine college credits (three per year) through First Star by the time he graduates from high school.

Why UConn?

The Academy concept was developed by UConn alumna Kathleen Reardon ’71 (ED), Distinguished Fellow and founding board member of the national First Star organization. It grew out of her book Childhood Denied, written with husband Christopher Noblet, also a UConn alum and author of the UConn Academy’s business plan.

A former UConn faculty member, Reardon is now a business professor at the University of Southern California Marshall School. She has been instrumental in launching several First Star Academies, including the initial one at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 2011. Because of her history with UConn, Reardon says she was eager to start an Academy here, and approached UConn President Susan Herbst with the idea.

“Higher education is all about access to opportunity, and we couldn’t feel more strongly about that at UConn,” Herbst says. “Establishing the First Star Academy allows UConn to provide life-changing opportunities to these deserving teens. The perseverance they’ve developed by necessity as children in the foster system is exactly the kind of attribute that will help them thrive in college careers, given the right supports and resources to make the transition. We’re excited to play a role in that through the UConn First Star Academy, and we’re grateful to the state Department of Children and Families for supporting this immensely important initiative.”

UConn is uniquely qualified to host a First Star Academy, points out Maria Martinez, assistant vice provost of the Institute for Student Success. Martinez directs the Center for Academic Programs, which has a long history of running summer residential programs for first-generation, low-income, underrepresented students.

Rayford concurs. With its 40-plus year history of success, UConn is in the top echelon of institutions in terms of preparing students for college, he says. That, combined with DCF’s post-secondary education program – which last year funded college or vocational school for more than 600 young people in its care – makes this “a perfect marriage,” he says.

“We want to become the model to follow,” Martinez insists.

According to Reardon, UConn is well on the way. “Given UConn’s deep experience working with underserved students, this could be our model program,” she says. “I’m very impressed by the students and by the work the staff is doing. You have exceeded my vision,” she told students and staff during a recent visit.

The young participants share Reardon’s regard for the program, and especially the staff.

“The TCs [tutor/counselors] are very inspiring,” says Kate. “They’re there when you need them. They help you. They give you great advice. I feel like they’re my big brothers and sisters.”

“Emily,” a high-school sophomore from Groton, agrees. “They didn’t have to come here for the summer and do this for us,” she says. “They changed my life. This whole program changed my life.”

* The names of program participants have been changed to protect their identities.