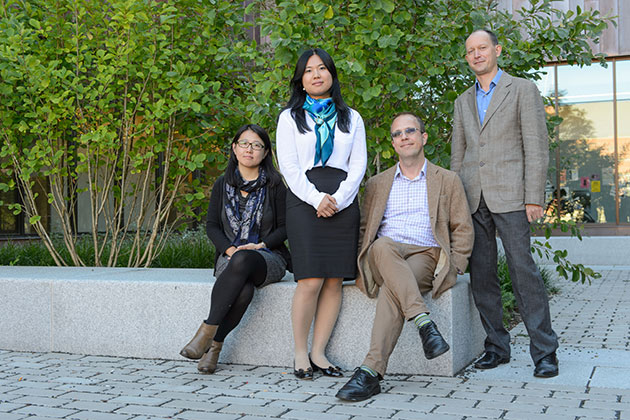

With the addition of six new faculty, an emergent critical mass of Asian and Asian American Studies scholars has formed at the University of Connecticut.

The growth of the program has turned UConn into a distinctive center that focuses on Asian populations not just in Asia, but across the world – giving an increasingly global perspective to studies of Asian peoples.

On the whole, the new group of professors brings a greater emphasis to cultures formed from diasporas, or the scattering of people from their traditional homeland; and alternate histories, such as local or regional histories that haven’t traditionally been recorded.

“This focus allowed us to hire people who significantly build upon the established field of Asian studies by engaging contemporary and modern questions,” says Cathy Schlund-Vials, associate professor of English and director of the Asian American Studies Institute. “We’re moving from traditional area studies to a more global focus. At the same time, we are expanding the internationalist work of the faculty in Asian American studies, whose work is shaped by considerations of migration, movement, and diaspora.”

Daniel Weiner, vice provost for global affairs, says, “It’s a very exciting time to invest in faculty with expertise pertaining to Asia. It’s also exciting that UConn has an opportunity to construct the study of Asia in a unique way through inclusion of transnational and diasporic studies.”

A wealth of untold history

Victor Zatsepine, new assistant professor of history and Asian American studies, grew up in Russia and moved to Beijing in 1989 to attend college at Beijing Language and Culture University. His travels took him through the very northeastern part of China, across the Manchurian border. It was a very unfriendly place, he recalls, but the people of the area stuck in his mind.

“I wanted to know: What is the story of these ordinary people who live in this very rural area on the border of China and Russia?” he says. “This is what propelled me to think about the frontier society and how tensions evolve there.

“I’m interested in regional histories, not traditional country boundaries,” he adds. “How do the people on such a border identify themselves?”

After a decade working as a researcher at newspapers in China, Zatsepine returned to school to earn his MA at Harvard and his Ph.D. in history at the University of British Columbia. His current field work involves returning to the Manchurian border of China and Russia to research and document the area’s history through archives and manuscripts.

Many people still look at Asia through the lens of categories dating to the Cold War, he says, which don’t accurately describe what’s going on today. Areas referred to as “East Asia” and “Southeast Asia” comprise many different peoples and histories, he says.

“History often focuses on the people who have financial means to record their history,” he says. “It’s up to social historians to uncover the rest.”

This semester, Zatsepine is teaching a class on the histories of East Asia, which he hopes will help students understand the diversity within Asian cultures. More than anything, he hopes some of his students take part in exchange programs in Asian countries.

“An exposure to another culture at this stage of their lives will stick with them for the rest of their lives,” he says. “It will destroy the stereotypes of what Asian history is.”

This land is your land

Unlike in the U.S., where land can be bought and sold by individuals, companies, and the government, in China all land is publicly owned, and a market for the land only emerged in the past 20 years.

What this means, says Meina Cai, a new assistant professor of political science, is that even though a Chinese citizen may lease the right to build a house on a tract of land, they don’t actually own it.

But the Chinese government has begun to see rural, residential land as commercially valuable, and in recent years has begun staking its claim to the land that many Chinese people have been living on for decades. Instead of risking public ire by simply kicking them out, the government often tries to entice people to move to cities with incentives, such as social welfare.

That’s where Cai comes in.

“This is the main source of social instability in China: land grabbing,” she says, noting that China spends more on maintaining social stability than it does on national defense.

Cai wants to know exactly how this land shuffling works at a local and regional level. She travels to coastal areas in China and interviews government officials, political elites, and villagers to find out how this new market for public land is evolving.

“When the government takes your land, how does it work? What compensation do you get?” she asks. “What can you do to bargain? What kind of return do they give peasants? Are they forcing them off their land?”

Cai uses case studies and survey data as discussion and analysis material in her courses. This semester she’s teaching Chinese Government and Politics, which covers the political, economic, and social challenges of the Chinese government.

Having grown up in China and dedicated her research to studying it, Cai is excited about the recent investment at UConn in Asian and Asian American Studies.

“Asian studies is an area the University is trying to expand,” she says. “The University really cares about this for the future.”

The several other new faculty involved in Asian and Asian American studies include Yan Geng, assistant professor of art and art history; Brad Simpson, associate professor of history; Nu-Anh Tran, assistant professor of history (arriving in fall 2014); and Peter Zarrow, professor of history.