Jeremy Teitelbaum, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, is a guest contributor to UConn Today. Read his previous posts.

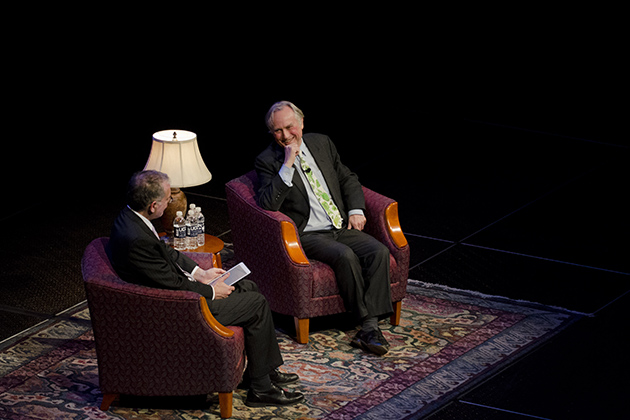

Yesterday I had the privilege of speaking with Richard Dawkins, renowned evolutionary biologist and outspoken atheist, in a public interview at our Jorgensen Center for the Performing Arts. The auditorium was packed to capacity, the energy was tangible. I was struck by the audience’s interest in scientific questions during the Q&A period.

Here are some edited highlights of the evening’s discussion.

Jeremy Teitelbaum (Me): Your career started in the 1960s at Oxford, less than a decade after the first description of the structure of DNA by Watson and Crick. What was the intellectual climate like for biologists at that time?

Richard Dawkins: It was a remarkable time. What [Watson and Crick] showed is something that in hindsight had to be true: that genetics is digital. And it had to be true, because only a digital system would have the fidelity to do what we know is done in natural selection. Natural selection does not work without mutation, but we know that the amount of mutation needed for natural selection to work is very very low. So the whole of modern biology is in a sense a branch of information technology, a branch of computer science.

Me: Perhaps we could talk for a moment about The Selfish Gene and your subsequent work on evolution.

Dawkins: Darwin knew that the swiftest runners, the ones with the keenest eyesight, the ones with the sharpest claws or the most attractive feathers, would ultimately survive. What I did was to take the logical conclusion of that and say: What actually does survive? The thing that can be transmitted through an indefinitely large number of generations – perhaps millions – is the gene. How are they successful? Well, they’re successful by building successful bodies. The exact nature of the success depends upon the species: birds are good at flying, moles are good at digging, gibbons are good at swinging from the trees, and so forth.

So why the “selfish” gene? At the time there was a spate of work about why animals are sometimes altruistic: why they help each other, why they restrain themselves in fighting. Konrad Lorenz and other biologists thought it was because it would be good for the species. But this was the wrong way to look at it. The right way is that the best way for a gene to look after its own interests is to program the body it’s in to be altruistic. So you can think of the individual body as a survival machine for its genes. That body will die and be cast aside. The only thing that will continue to the next generation is the genes.

Me: It’s been 35 years since that book was published. Would you make any changes to your selfish gene theory today?

Dawkins: The message still remains: the variations in genes are reflected in bodies, and those variations in bodies are what cause some genes to remain and others not to. And that’s all that matters from the selfish gene point of view. Which is somewhat to my regret, because scientists often gain prestige by admitting their mistakes. And in this particular case, I think I was right.

Me: A Pew Research Center study says that a third of Americans believe that humans have always existed in their current form. Why do you think evolution is still such an issue in American society?

Dawkins: It’s worse than this, I think – some polls put it at almost half of the population. And it’s also that many people actually believe that the world is only 10,000 years old. If you do the sums, it’s comparable to believing that the North American continent is about eight yards in width. That is the magnitude of this error. It is to me baffling, and it shows that we scientists have not met our educational responsibilities.

Me: What’s a reasonable strategy to combat this resistance to evolution? For example, I have here a pamphlet I received outside the theater tonight that reads: “Are you really an accident of nature?”

Dawkins: If you think that Darwinian natural selection is all an accident, then no wonder you don’t believe it. The whole point of what Darwin achieved was to get away from accident. The complexity of a living thing is prodigious. And one thing defining complexity is statistical improbability. So the only solution to achieving these complex organisms is what Darwin discovered: gradual, incremental improvement over time.

Me: You’ve taken quite an aggressive position that there is no God, and you promote atheism. How did this become important to you?

Dawkins: I’m not aggressive! Well, perhaps I’m angry. But I do believe in truth. I am moved by the beauty of life, as it has evolved. I think any child who is being denied that knowledge is being cheated. It’s wicked that children are being brought up in that way by parents, teachers, priests – deliberately, systematically deprived of that knowledge.

I think it’s a foolhardy act to fall back on the same explanation that Darwin exploded when he solved that big biological problem. What Darwin achieved should be a cautionary tale not to fall into that same kind of trap of saying, “Oh, we don’t understand it, therefore there must have been a designer who did it.” We got that wrong till the middle of the 19th century. If an eye is statistically improbable, how much more statistically improbable would an intelligence capable of designing an eye, or designing the laws of physics or quantum theory, actually be? You have simply erected a new problem analogous to the problem of explaining natural complexities. It’s a cowardly evasion, it’s lazy. What we should be doing as scientists is rolling up our sleeves and saying, right, Darwin solved the big problem. Now let’s take that as encouragement to solve the other big problems, like the origin of life and the origin of the cosmos.