When the poet Marianne Moore visited UConn in 1964 as the first Wallace Stevens visiting poet, tea with cucumber sandwiches was served by graduate students and their mothers in a big striped tent set up for the occasion. Moore wore one of her trademark hats. “It was right out of Oscar Wilde,” recalls a faculty member, now retired, who was there.

When Allen Ginsburg was the visiting poet in 1970, a dinner was held in his honor at the former Faculty Club. But he didn’t eat, preferring instead to table hop, lecturing the insurance company executives who funded the Stevens program about ending the Vietnam War. A faculty member recalls seeing him in the restroom, smoking a joint.

For nearly 50 years, the Wallace Stevens Poetry Program has brought to campus some of the most distinguished and colorful poets in America and the world. It honors Wallace Stevens, the Hartford Insurance Company executive who became recognized as one of, if not the, leading modernist poet.

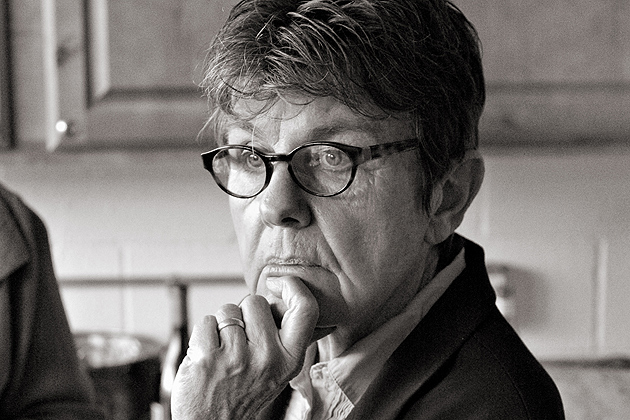

This year’s program again will feature a poet who has “skyrocketed into the public eye,” says V. Penelope Pelizzon, associate professor of English and chair of the Wallace Stevens Poetry Program Committee in the English department. The poet this year is Kay Ryan, winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in poetry and a recent winner of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant. A former U.S. poet laureate, Ryan has taught remedial English for more than 30 years at a community college in California. She didn’t publish her first book of poetry until she was 40 years old.

She will read her work and meet with students at UConn on April 9. The next day she will read for and meet high school students at the Greater Hartford Academy of the Arts.

Hearing firsthand a premier poet is an opportunity for Hartford and UConn students that makes the program particularly meaningful, says Pelizzon. Ryan is “someone [whose work] I’ve been teaching for a long time, and students have responded very well,” she says.

The Wallace Stevens program, funded since its inception by The Hartford (now The Hartford Financial Services Group), also recognizes student poetry. Prizes of $1,000, $500, and $250 are awarded each year at UConn, and the winning poems are published in the University’s literary journal, The Long River Review.

A Hartford-wide poetry contest open to juniors and seniors in high school also awards a $1,000 scholarship to a winning poet, funded by The Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens, http://www.stevenspoetry.org/index.htm (he could rub some people the wrong way, so he had his enemies, they explain).

Glen MacLeod, professor of English and a Wallace Stevens expert, recalls an anecdote told by a Hartford Insurance retiree at the dedication of the Friends’ Wallace Stevens Walk in Hartford. The retiree had been a young staff member when Stevens worked for the company. He would see Stevens in the restroom but was afraid to say hello, knowing his reputation for gruffness. One day, Stevens turned to him and thanked him for never trying to start a conversation: “I appreciate that,” he told the young man.

Stevens saw no contradiction in being a poet and an insurance executive, MacLeod says. He kept the two separate, traveling to New York City to visit museums and literary friends and not talking with colleagues at The Hartford about poetry.

Stevens died in 1955. In the last five years of his life, he won the Pulitzer Prize and twice won a National Book Award. But MacLeod’s favorite Stevens poem is one of his first, from 1915, “Sunday Morning,” an uncharacteristically romantic piece that he describes as “almost like Keats.”

It introduced a main theme of his work, the death of God and the role of religion in society, MacLeod says. His later works, more abstract, often dealt with those ideas.

Joseph Cary, professor emeritus of English who retired in 1991, was an assistant professor when he was tapped to be the first chair of the Wallace Stevens program by Leonard “Pete” Dean, the department head who came up with the idea and first contacted The Hartford about supporting it.

Cary is the faculty member who recalls the colorful incidents of the program’s early years. He also recalls how some poets have made a special connection with students. Robert Lowell went out of his way to shake hands with all the students and to treat them as fellow poets, he says.

For a program that has brought nearly every major American poet to UConn, that is the goal, Pelizzon says.