When the director of the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute suggested an art exhibition this year at the William Benton Museum of Art to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, the initial idea was to contrast works by Southeast Asian artists with works by American artists.

However, in discussions with the director of the Benton, the conversation moved to a focus on what the war was about and to the protests against the war and how artists responded to it.

“There still seems to be an immediacy with the Vietnam War because politicians will access it. How many times is Vietnam invoked as an analog about what’s happening in Iraq and Afghanistan, with mentions of a quagmire – that Afghanistan is not going to be another Vietnam?” says Cathy Schlund-Vials, director of the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute and an associate professor of English. “But it’s very much in the past. I wanted to bring up a conversation of what was this war?”

The exhibition, which continues through Aug. 9, includes selections from the University’s Archives & Special Collections that include the Poras Vietnam War Memorabilia Collection, Alternative Press Collection, and University Photographs Collection. The works include prints, paintings, and photographs by professional artists, as well as anti-war posters and pamphlets produced by UConn students at the time.

Schlund-Vials says that many of today’s students know very little about the Vietnam War. When she teaches classes covering the war, she provides her students with context for the war, and also the history of student protest culture: “I want to highlight that there is a long history of student protest, and there were particular investments with a conflict that was highly unpopular.”

She hopes students look at the parallels and some of the disjuncture they recollect with Iraq and Afghanistan. “Of course, it’s very different,” she says, “because there was a draft [during the Vietnam War].”

She notes that the news cycle at the time also allowed for more concentrated engagements with the war. “Now we’re dealing with a news cycle that’s overwhelming. [Today’s] students know the images and the iconography of the war, but they don’t understand the conditions that brought it into being, the politics; that it was a very different conflict in many ways.”

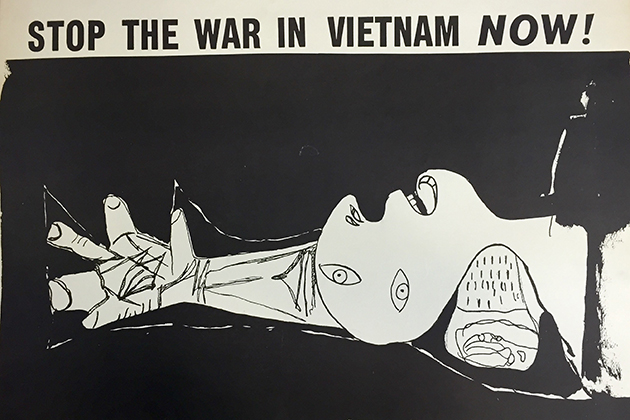

Among the works on display at the Benton is the poster “STOP THE WAR IN VIETNAM NOW!”(circa 1970), featuring a detail from Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica,” one of the most famous anti-war paintings from 1937 that protested the Spanish Civil War. “HANOI- ITS [sic] THE SAME WAR – KENT,” a 1970 poster, references the shooting of four students at Kent State University during the Vietnam War protests. There are also copies of the Nov. 12, 1969 edition of “UConn Free Press,” a student publication, displaying a map of the planned protest march in Washington, D.C. The march started from the U.S. Capitol Building, and moved down Pennsylvania Avenue to the area known as The Ellipse, directly across from the White House.

For Schlund-Vials, looking more closely at the Vietnam War was not just a part of her scholarship, it also was a journey through her past. She and her twin brother were born in Thailand near Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, which was used during the war by allied pilots including Americans, following a liaison between her Cambodian mother and an American serviceman. She and her brother were later adopted by a U.S. Air Force master sergeant and his Japanese wife seeking to adopt AmerAsian children.

While doing graduate work at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, focused on Asian and Jewish-American writing – “two model minorities who are oftentimes compared to each other but rarely discussed” – she researched a chapter comparing Holocaust narratives to Cambodian genocide narratives. This led to her book, War, Genocide, and Justice (University of Minnesota Press, 2012), which included a study of the connections between the Khmer Rouge – the Cambodian Communist followers of the North Vietnamese Army – and the U.S. bombing of the Cambodian countryside during the Vietnam War.

“The conditions that brought me into being were connected to that,” Schlund-Vials says. “I find I’m marching more and more back to the war, because there are so many assumptions made about it.”

She says her research has brought her to the realization that people’s individualized recollections have nuanced the war: “When I talk to Vietnam War veterans, what they remember about the war is not the Hollywood treatment of the war. They remember the Vietnamese translator, the families they got to know, or the children they would see around the base.”

Schlund-Vials wanted the Benton exhibit to recollect and honor those memories, but also to take the protest movement seriously. “That’s what it ended up becoming,” she says. “Everybody had a relationship to this war at the time.”

“Remembering the Vietnam War” continues at the William Benton Museum of Art, 245 Glenbrook Road, through Aug. 9. For more information, go to the Benton website.