Brendan Smalec ’16 (CLAS)(SFA) wanted to be a doctor. The Cheshire native had just started at UConn and was already in the Honors Program, with a double major in art history and molecular and cell biology, but he thought a stint working in a research lab would be good experience. So he wrote up a proposal to study cancer in mice.

“I’m too embarrassed to even look at it now,” Smalec cringes. In hindsight, he thinks it was probably simplistic or ridiculous. But the Holster Scholar program judges thought it was good enough to award him funding, and assigned him to work in UConn genomicist Rachel O’Neill’s lab.

O’Neill, a professor in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, put Smalec to work looking at Harderian gland adenocarcinomas in mice. Adenocarcinoma is the technical term for cancer that starts in gland tissue. People commonly get adenocarcinomas in the breast, lungs, prostate, and colon. The inbred mice in O’Neill’s lab got it behind their eyes, but it quickly spread throughout their bodies. O’Neill and Smalec thought the cancer’s DNA might give clues as to why it spread so quickly, perhaps shedding light on how human cancer spreads.

Smalec started looking at sections of DNA that were expanded, duplicated over and over. This is common in cancer cells, and is one of the things that makes them abnormal and dangerous. Once Smalec found an expanded section of DNA, he’d try to map it back on to the cell’s intact DNA to figure out where in the chromosome it came from. Chromosomes are the structures cells use to organize DNA. They are usually made of two long strings of DNA, linked together in the middle or the end so that they look like Xs or Vs.

One of the expanded sections of DNA he found always seemed to be touching the centromere of its chromosome. The centromere is the spot where the chromosome’s two strings of DNA join up, the cross of the X or the tip of the V.

“I didn’t know what to think, because I was new,” Smalec says. He’d been in the lab just two weeks, “but I knew it wasn’t what we were looking for and I wasn’t tuned into evolution.” But evolution is where he ended up going. He started looking at the DNA of six other species of mice related to the ones in the lab. And all of them had this same DNA sequence stuck to their centromeres. Smalec started to wonder whether this particular piece of DNA played a role in centromere formation, or maybe in the speciation events, when one type of mouse splits into different species.

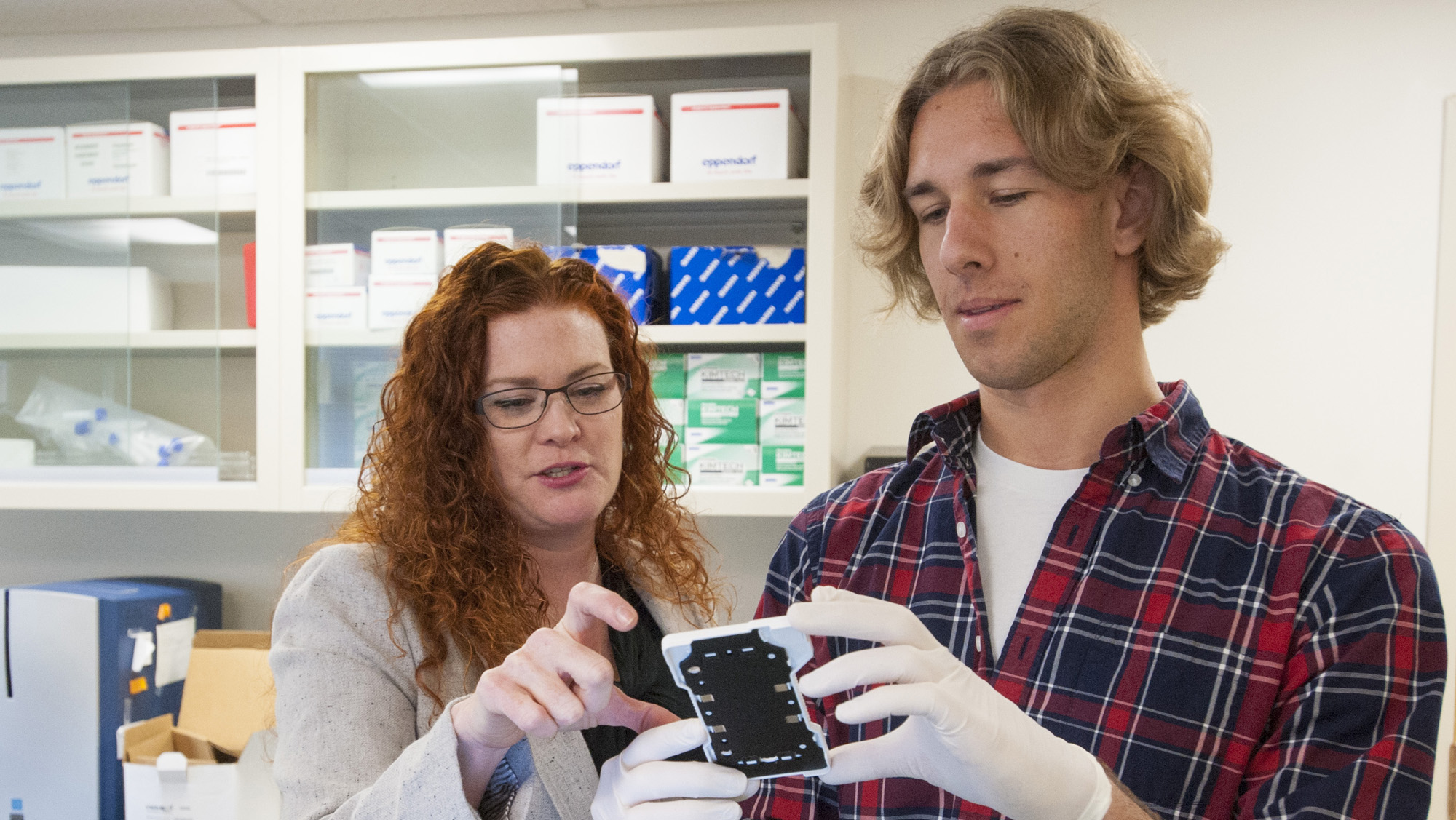

After two and a half years of tracking this DNA sequence through different rodent lineages, Smalec and O’Neill will submit a paper on it to a scientific journal sometime this autumn. And it won’t be just a line boosting Smalec’s medical school resume. Somewhere along the way, Smalec decided that rather than become a doctor, he’d like to continue in research and get a Ph.D. in genetics and evolution.

“I’m kind of sad,” O’Neill jokes. “If I’m sick, Brendan would’ve been a really good doctor.” But she’s also pleased at his new path, and says he brought a lot of insight and creativity to her lab. “This is a two-way street. We talk! He brings a lot to me, just as I bring to his work.”