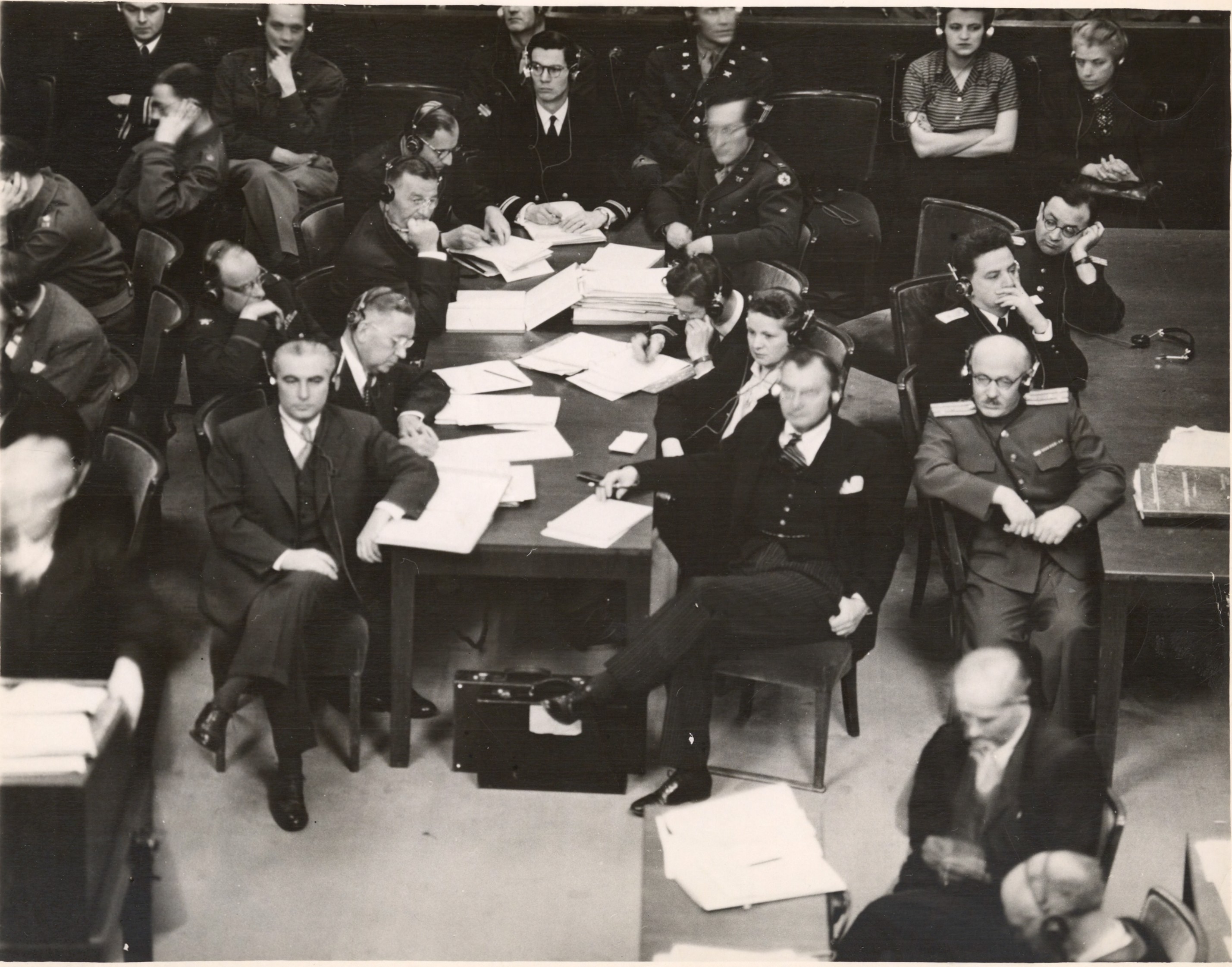

After spending the summer of 1945 as the executive trial counsel and supervisor for the United States team in Nuremberg, Germany, 70 years ago this week, while preparing the prosecution against the 23 leaders of Nazi Germany about to be tried before the International Military Tribunal, Thomas J. Dodd of Connecticut wrote one of his nightly letters home to his wife Grace.

“This is a date to be remembered,” the then-38-year-old Dodd wrote on Nov. 19, 1945, of what has become known as the Nuremberg Trials. “The courtroom was crowded. The defendants made quite an appearance … I had the feeling that I was witnessing and participating in a history-making event.”

Dodd’s preparation of the 50,000 documents used in the prosecution was essential in bringing to conclusion the record of Germany’s atrocities leading up to, and throughout, the Second World War. The Nuremberg Trial Papers, as well as materials from his years in the U.S. Senate from 1959 to 1971, are housed in the Archives and Special Collections Department of UConn’s Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, which was dedicated in his memory 20 years ago during ceremonies featuring remarks by President Bill Clinton and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, who was a prisoner in the Nazi concentration camps.

“The main legacy of the Nuremberg Trials is the melding of international, global commitment to holding individuals accountable for human rights abuses, regardless of where they are in positions of power in the state,” says Glenn Mitoma, director of the Dodd Research Center and assistant professor of human rights and education. “The trials are the kind of ‘Big Bang’ moment in the emergence of human rights in the second half of the 20th century. The Dodd Center is, in fact, the result of that legacy of Nuremberg. It was part of a resurgence of a concern for international justice.”

Setting a baseline for universal human rights

The charges brought against Nazi leadership – Hermann Göring, Reichsmarschall and first head of the Gestapo; Karl Donitz, who initiated the U-Boot (German for U-Boat) campaign; Rudolf Hess, deputy Führer; and Martin Borman, the Nazi Party secretary, among others – included participating in a conspiracy to commit crimes, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Three individuals were acquitted of charges, seven were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 10 years to life, 11 were sentenced to death by hanging, and one was neither acquitted nor found guilty. Borman died while escaping Germany in 1945 and was tried in absentia. Göring committed suicide before his scheduled execution.

The Geneva Conventions of 1864, 1906, and 1929 had established international standards that were understood to encompass the humanitarian treatment of prisoners and of citizens in occupied territories during war. Mitoma says, however, that at the time of the trials, criticism centered on the charges brought against the defendants for crimes against peace and crimes against humanity because such charges had not previously been established as part of international law.

“The kind of guiding ideology of the Nuremberg Trials was laying down principles that there is a baseline of natural law of universal human rights that’s there at all times,” he says. “That guiding theory informs the emergence of human rights; the idea [is] that we have to advocate for human rights on a global level, and there are dimensions to our basic humanity that give us moral rights that form the fundamental basis of our morality and our humanity.”

In late 1948, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was championed by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who served as U.S. delegate to the UN General Assembly and chair of its Human Rights Commission. However, human rights issues did not become a top concern for the United States until the Cold War with the Soviet Union worsened, says Frank Costigliola, professor of history and a scholar on the Cold War.

“The United States was kind of shy of any international controls,” he says. “They were afraid the Soviet Union would make up charges. After Eleanor Roosevelt left the Truman Administration, no one else was arguing for human rights. Setting up international controls could impinge on U.S. sovereignty.”

Confronting the past

Meanwhile, in postwar Germany, a movement had been gaining momentum to bring to justice German citizens who had carried out many of the atrocities ordered by Nazi leadership. This movement focused on violations of German law, even as the divided nation – separated as one of the opening salvos in the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union — began to confront its past.

In late 1958, the Central Office of the State Justice Administration for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes was created in West Germany to find those who had carried out the Nazi agenda and, if appropriate, to hand them over for prosecution. Over the next 50 years, more than 7,000 investigations were conducted, involving more than 100,000 Germans, says Charles Lansing, associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, who specializes in the history of the Third Reich. He is writing a book about the Central Office investigations with the working title, The German Nazi Hunters: The Central Agency and Germany’s Belated Search for Justice.

“Those tried at Nuremberg are the tip of the iceberg,” says Lansing. “We estimate there were at least 100,000 Germans who were shooters, camp guards, or who had an active role in persecution of the Jews. The Germans began a process to figure out who committed what crimes, when, where, and against whom. It’s a difficult story of confronting the Nazi past. It’s a story full of progress and setbacks. I don’t think there’s any other country that’s faced a criminal past as honestly and fully.”

The trials also provided a template for the international courts and tribunals that subsequently were established during the remainder of the 20th century and in the new millennium, notes Richard Wilson, Gladstein Distinguished Chair of Human Rights and professor of anthropology and law. International tribunals to prosecute a variety of criminal actions, trade disputes, and human rights violations have covered issues throughout the world, including Africa, the Caribbean, South America, Europe, and in such countries as Lebanon, Cambodia, and East Timor.

Wilson says subsequent international tribunals, such as those held starting in the 1990s for criminal prosecutions in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda, “looked back to Nuremberg and were greatly influenced by it. They learned from [Nuremberg’s] successes and mistakes. They gave defendants much stronger due process protections. They also drew from the body of law created in Nuremberg, such as the idea of joint criminal enterprise as a way of encapsulating the orchestrated collective nature of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.”

A ‘double-edged sword’

The establishment of the International Court of Justice in 1945 as the judicial branch of the United Nations to address general disputes between nations, followed by the creation of the International Criminal Court in 2002 to handle criminal prosecutions, have provided a forum for addressing international legal issues, but with mixed results, according to Mark Janis, William F. Starr Professor of Law at UConn Law.

“The International Criminal Court has been less successful than Nuremberg,” Janis says. “It’s been hampered by all sort of things. People who are with it say there are good things about it, which there are. So far all of the ICC prosecutions have been aimed after Africans, which has been criticized as neo-colonialism. It seems to be specific toward smaller countries.”

He adds that the use of international law has proven to be a double-edged sword, with nations accusing others of human rights violations while being criticized for their own domestic practices.

Still, the focus on international law that began with the Nuremberg Trials 70 years ago has continued to expand interest in the issues connected to the conduct of nations and human rights issues.

“All of this activity is hugely important for international lawyers,” Janis says. “There’s much more going on in all of these areas than 20 years ago. There is more international law for students to study, and there are possible careers. Nuremberg and its legacy informs a lot of the work I do in international law.”

Scholarly interest in the Nuremberg Trial Papers is ongoing. The Archives and Special Collections Department of the Dodd Research Center opened up the digitized files in 2013, and through 2014 the papers were accessed online 3,700 times by those seeking information. The blog Nuremberg at 70 was also established by the staff of the Dodd Research Center to address various aspects of the trials.

Soon after the dedication of the Dodd Research Center, UConn designated human rights as a University priority and, in 2003, the Human Rights Institute was established. Uniquely organized around joint faculty appointments made in partnership with the departments of anthropology, economics, history, philosophy, political science, sociology, and the schools of law and business, the Human Rights Institute currently runs undergraduate majors and minors in human rights, offers a Graduate Certificate in Human Rights, and sponsors three thematic research clusters centered on health and human rights, humanitarianism, and economic and social rights.

.