Update, March 16: As President Barack Obama announces he is nominating veteran appeals court judge Merrick Garland to be the next U.S. Supreme Court Justice, we revisit last week’s post on the Supreme Court nomination process.

With President Obama expected to announce his nomination soon, the battle over filling an unexpected Supreme Court vacancy at the height of the 2016 presidential primary season, has upended political debate. Democrats are pressuring Republicans – who control the Senate – to grant Obama’s nominee a hearing this year. The GOP has argued that Obama should allow his successor to make the next court pick, and have vowed to block any attempt to confirm a new justice this year. Yesterday, the debate was stoked by an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal by Republican Sen. Ted Cruz, who is running for President and is no doubt hoping he’ll be the one making the appointment.

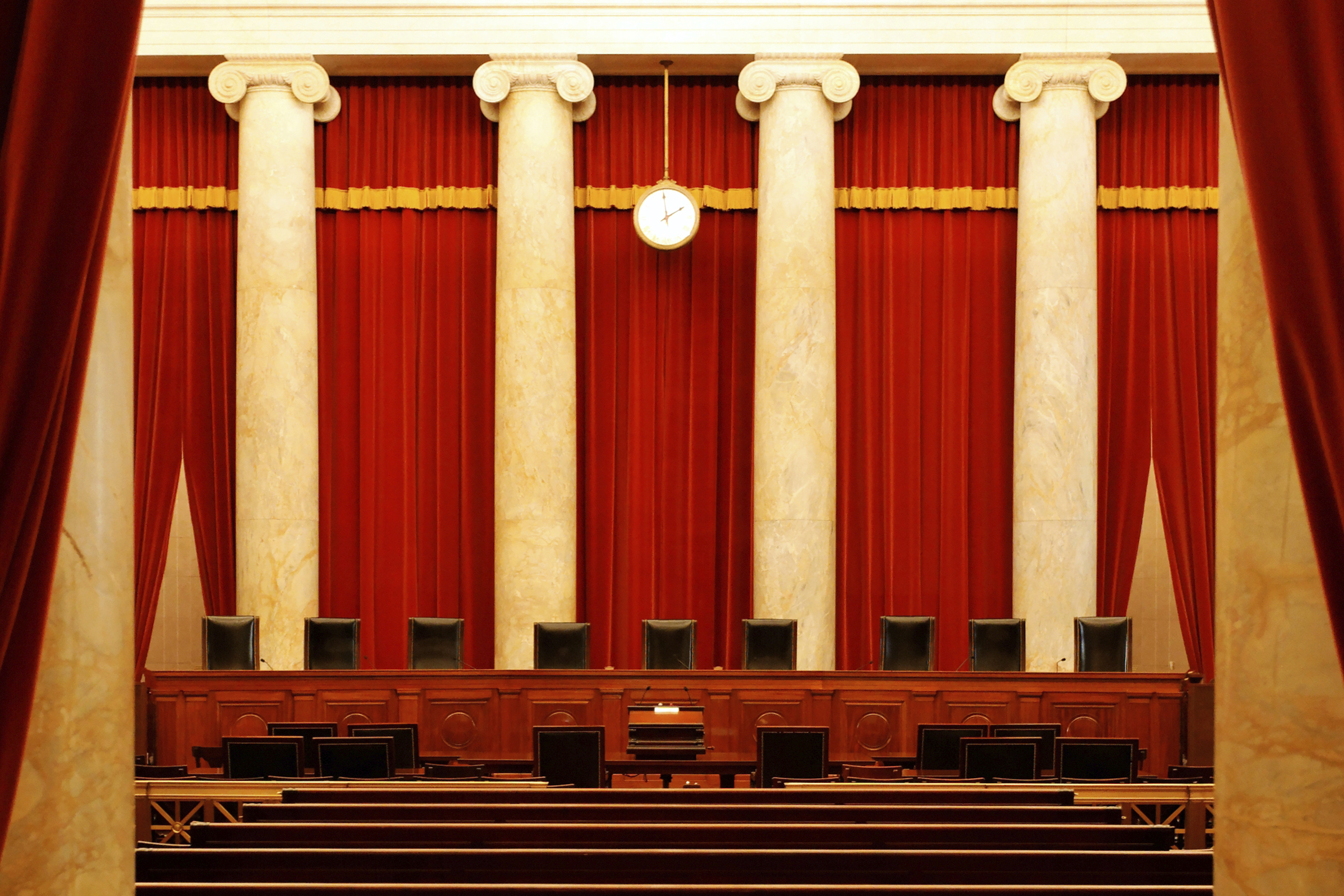

The tension surrounding the modern Supreme Court nomination process underscores the high stakes at play: the next justice to the high court will play a crucial role in determining policy in America for decades to come. Professor David Yalof, head of UConn’s Department of Political Science, an authority on the politics of Supreme Court nominations and author of Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of the Supreme Court, discussed the current nominating process with UConn Today.

Q. How important is it to get a quick replacement for Justice Scalia to have a fully staffed Supreme Court?

A. The Supreme Court has gone short-staffed for extended periods in the past. Justice Robert Jackson took a leave of absence from the court in 1945 to prosecute war criminals at Nuremberg. Justice William Douglas suffered from a horse riding accident in 1949 that kept him away from the court for many months. The difference here is that the short-staffed court of 2016-2017 would arise from a deliberate political choice. When the court splits 4-4 in a case, the court announces that the lower court case is “affirmed by an equally divided court.” That not only leaves the lower court case unaffected; it also means that widespread differences among the different circuits will remain as well. Many important issues may have to wait a year and a half or more to be resolved.

Q. The Constitution leaves it up to the Senate to make up all the rules governing the selection of a replacement for a dead judge. Why not simply follow the constitutional process and if, during confirmation hearings, the nominee turns out to be unacceptable, then refuse to consent?

A. The Senate is controlled by the Republicans, and they are reluctant to let President Obama fill Justice Scalia’s seat with anyone, no matter how qualified. They believe their party may win the next presidential election, and that would give a president from their own party the chance to replace Scalia. Moreover, even if the Democrats win the White House once again, they believe little would be lost in waiting – it puts them right back to this same point. Thus so long as the public does not punish them for stalling, the Senate leadership has no incentive to go through the motions and hold hearings in 2016.

Q. Republicans are insisting that voters make a decision on who the next president will be, before anyone gets to name the next nominee. With a vacancy that could shift the ideological balance of the court, what is wrong with that proposal?

A. There’s nothing wrong with that proposal in theory. In practice, however, it establishes something of a dangerous precedent. After all, voters did make a decision on who the president would be in 2012. They chose President Obama to serve for four years. Why doesn’t the electorate of 2012 get to influence who chooses the next Justice? The danger is that by refusing to hold hearings, the Senate may be viewed as refusing to validate the decisions made in previous elections. And then what happens when a vacancy arises in 2019? Why should the electorate of 2016 be able to influence that choice?

Q. There is some speculation about a consensus pick. Do you consider the possibility of a compromise replacement realistic?

A. The possibility of a compromise replacement emerging is extremely low, though it is not impossible. Every Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee has declared that he or she will not support hearings. Absent some shift in political conditions, they have staked out positions that will be difficult to abandon. On the other hand, if Republicans fear the political winds are turning against them and that the White House is all but lost, they may prefer a compromise nominee to a bold progressive appointed by a newly inaugurated Democratic president. So one never says “never.”

Q. Has partisan bickering and political posturing always been part of the process of selecting a Supreme Court Justice? What, in your view, would be the best case scenario for nominating and confirming a new justice?

A. The process has always been heavily contested, though there were some eras when the bickering didn’t result in rejected nominees (for example, from 1932 through 1967), while in other eras Supreme Court nominees have had a difficult time getting through. Divided government is often the culprit. Today we live in an era of sharply divided government, and the Republican Senate has been unwilling to cooperate with President Obama on any issue during his second term. So the Supreme Court selection process promises more of the same. Consider that while the last six Supreme Court nominees who came up for a Senate vote were all confirmed by relatively comfortable margins, in all six cases the president was submitting his nominee to a Senate controlled by his own party. That is not the case in 2016. The best case scenario for nominating and confirming justices is united party government.

Q. Does the rancorous debate surrounding the selection of a justice for the Supreme Court reflect a growing public view that the high court is just another political branch of government? Can the high court do anything to recapture its image as an impartial arbiter of laws?

A. The late Justice Scalia once said he welcomed the confirmation process as a plebiscite of sorts – it is the one chance the public has to weigh in (directly and indirectly, through their elected representatives) on the high Court itself and the role it should play in society. Of course the catch is that once a nominee survives the confirmation process successfully, he or she enjoys a lifetime appointment and never has to answer to the public again. The public gives the Supreme Court higher approval ratings than it does to Congress or the President, because most citizens do not view the court as a naked political entity. Regardless of what happens in the upcoming confirmation battle, the court will survive and will likely continue to enjoy its relatively exalted place in the public’s mind. The greater danger is that the public will become even more frustrated by the political branches of government.