Discussion of the Harlem Renaissance from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s is generally focused on the explosion of art and culture in what was then the nation’s largest African-American community. The work of writers, poets, musicians, and visual artists from that time period would go on to influence future generations in the United States and abroad.

But Harlem’s community theaters also thrived just north of the bright lights of Broadway during that era. A new book by UConn theater historian Adrienne Macki Braconi focuses the spotlight on these theaters and their critical role in fostering the social and political identity of African Americans who later helped launch the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

But Harlem’s community theaters also thrived just north of the bright lights of Broadway during that era. A new book by UConn theater historian Adrienne Macki Braconi focuses the spotlight on these theaters and their critical role in fostering the social and political identity of African Americans who later helped launch the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

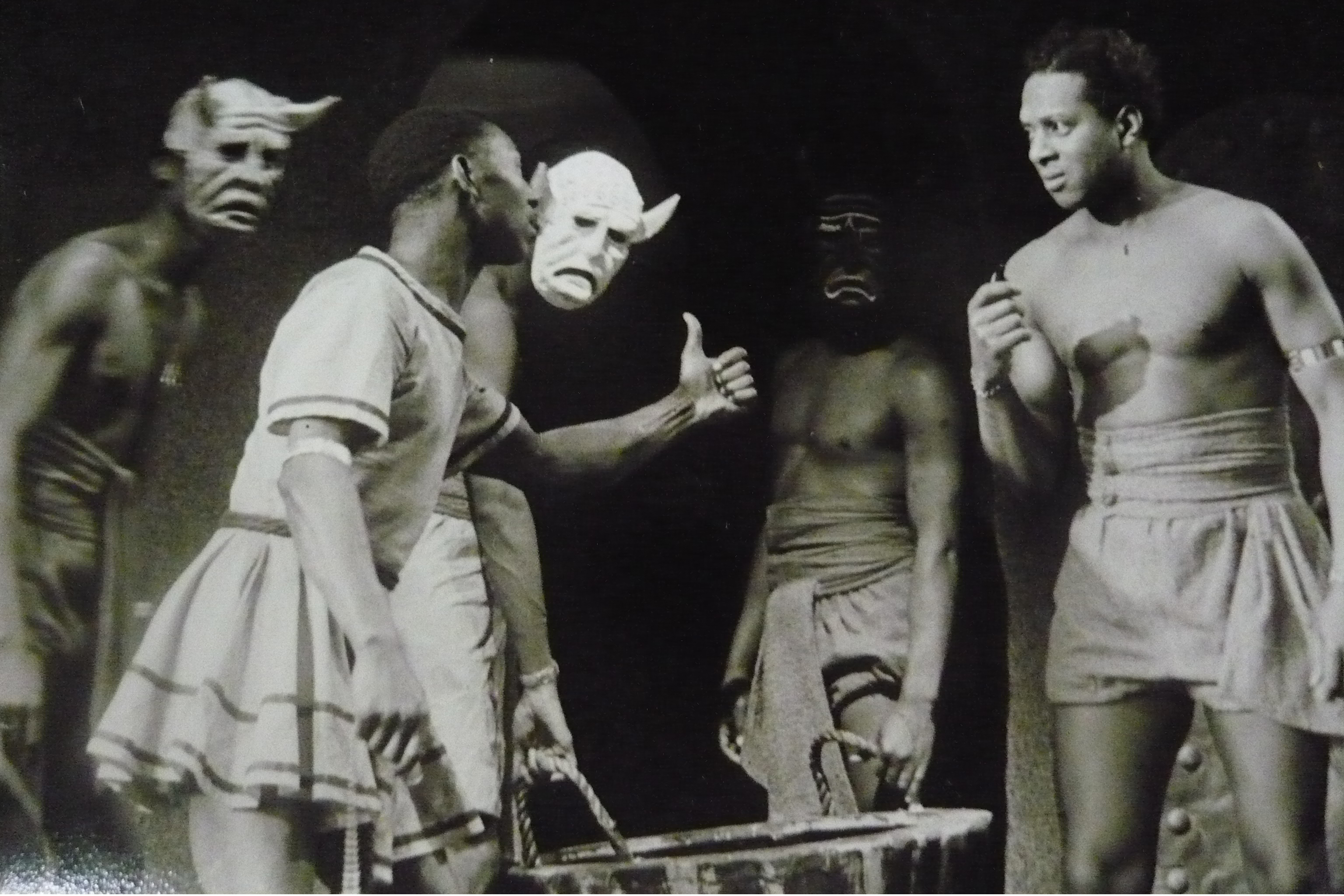

Braconi’s “Harlem’s Theaters: A Staging Ground for Community, Class, and Contradiction, 1923-1939” (Northwestern University Press) examines three major community-based theaters – Krigwa Players, Harlem Experimental Theatre, and Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project – and how their audiences viewed productions that raised issues of economic and political concerns. The audiences included leaders of the growing black middle class, who discussed issues in gatherings after the performances.

“In a time when it would be dangerous to protest or come together publicly, it became an area that was protected. It allowed them to assemble and circulate ideas in a way that didn’t draw negative attention and put them in jeopardy,” says Braconi, assistant professor of theater history, literature, and criticism in the School of Fine Arts. “They could come together and mobilize as a community around ideas and issues of concern.”

The book grew out of Braconi’s graduate research on the early Harlem theaters, largely community theaters that became centers of interracial and intraracial exchange. Through her research, she noted the recurrence of familiar names involved in after-theater events, including W.E.B. Du Bois, the historian, sociologist, and civil rights activist; Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., leader of the Abyssinian Baptist Church; Louis T. Wright, chairman of the NAACP from 1935 to 1952; and A. Philip Randolph, a prominent labor and civil rights leader.

Braconi says her interest in arts and activism and social change was spurred by the work of David Krasner, whose scholarship examined African-American theater in the early years of the 20th century.

“I was very interested in this time frame – 1920s through 30s and 40s – because I felt it had been dismissed and not investigated as fully as it should be,” she says. “One of the primary reasons this research was underutilized was because these local, community stages – and the works they produced – were dismissed. There has been greater interest in professional performances on Broadway by playwrights of color; in works with black performers and/or with black-themed subjects; in minstrelsy [white performers performing in blackface]; and in African-American performers who went on to Broadway – well-known actors like Ruby Dee and Paul Robeson. who had grown up in community-based theater and received their training there but went on to pursue professional careers.”

Braconi notes that productions by the Harlem Negro Theatre Unit (NTU) of the Federal Theatre Project provided opportunities for topical issues in the Harlem community to be addressed through theater. There was a focus on developing black-themed works by black artists who could get paid for their efforts.

“During this moment, we see a rush of black directors, actors, designers, and playwrights plying their craft in Harlem. For example, the Federal Theatre Project enabled Perry Watkins to go on to become the first professional African-American designer on Broadway and member of the scenic design union in 1939,” Braconi says. “Black stage managers, assistant directors, and a whole wellspring of talent received training, development, and money. It was like a salve for race relations during this very volatile time. It became a training ground for black artists that hadn’t been supported in the past.”

Such economic opportunity among the nation’s largest African-American community occurred as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program was still trying to recover jobs lost during the 1929 stock market crash and subsequent Depression era, even as the government struggled with its institutional racism and the mainstream entertainment industry continued to be dominated by white cultural values, she says.

As events abroad moved toward the start of World War II, the Federal Theatre Project was terminated after it became the target of early accusations of links to Communism by the House Un-American Activities Committee. However, as Braconi writes in the epilogue to “Harlem’s Theaters,” the ideas and relationships planted within the African-American community by these theaters would help change the nation.

“Each of these troupes pursued art in a community context as an alternative to commercial theater; each administrative team forged a web of connection among artists, educators, and activists in New York, thereby providing a spiritual base for the more political and radical black arts movements of the 1960s,” she writes. “These community-based theaters paved the way for such luminaries of the civil rights movement as the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., A. Philip Randolph, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by providing a dynamic, interactive site in which new visions of race relations and class were imagined and embodied, just as the foundations of black public networks were developed and rehearsed.”