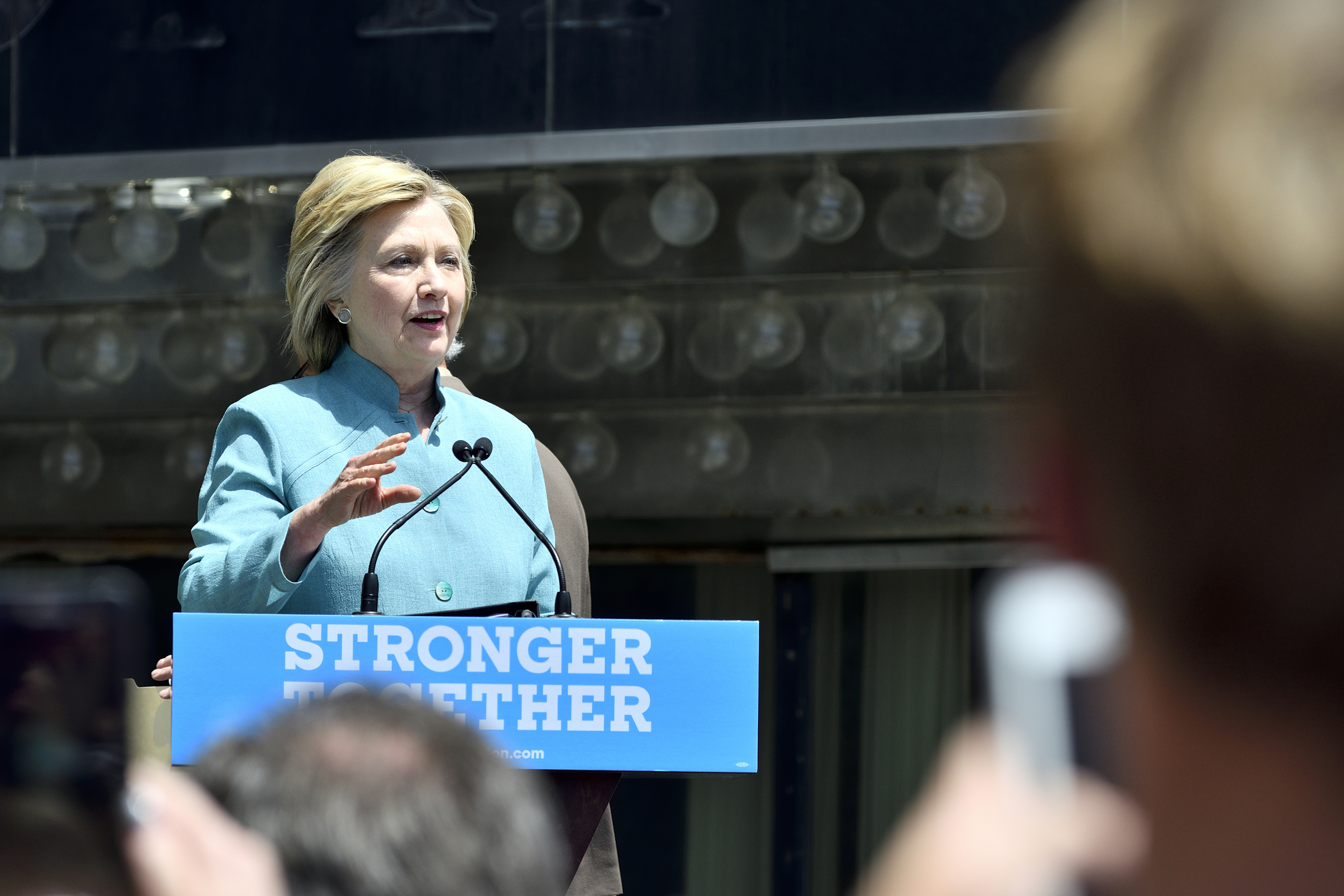

With Hillary Clinton poised to become the Democratic nominee in the upcoming U.S. presidential election, Theresa May having recently taken over as prime minister of the U.K. following its vote to leave the European Union, and Angela Merkel in her 11th year as Germany’s chancellor, the leaders of three of the world’s most powerful economies could all for the first time be women.

Pundits and bloggers are raising the question of whether this latest shattering of the glass ceiling for women in politics will make a difference in resolving issues between countries in the world, or preventing the escalation of issues into violent confrontations.

… as more women become actively involved in political decision-making, both the process and the types of interactions may change. Diversity in gender will thus bring with it diversity in viewpoints … — Mark Boyer and Scott Brown

Mark A. Boyer, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor and executive director of the International Studies Association, who has studied gender and negotiation, says female leaders have acted decisively in such situations in the past, but that a shift in “traditional gender roles and the policy action that emerges from them” will require still more women holding public office around the world.

“Having more women in decision-making roles and having more under-represented groups in decision-making roles has the potential to bring a diversity of ideas that might find solutions that weren’t considered otherwise,” says Boyer, co-author of a 2001 study “Gender, Violence, and International Crisis,” published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, that examined how female heads of state reacted to situations classified as international crises involving their country.

The study considered 10 crises in the late 20th century that in some instances led to armed conflict, such as India under Indira Gandhi, a 1971 clash with Pakistan; Israel led by Golda Meir, including several attacks on the country between 1969 and 1973; Pakistan under Benazir Bhutto, a clash with India in 1990; and the United Kingdom led by Margaret Thatcher during the Falklands War in 1982. In all of those situations, the female heads of state reacted to defend their country following violent or nonviolent attacks.

A 2009 study on “Gender and Negotiation” led by Boyer and Scott W. Brown, UConn Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Educational Psychology, published in the International Studies Quarterly, found that gender also plays a significant role in social and political interaction. The study concluded that “as more women become actively involved in political decision-making, both the process and the types of interactions may change. Diversity in gender will thus bring with it diversity in viewpoints, and diversity in the ways we consider the issues at hand.”

“Fundamental to all of this research is the idea that gender roles throughout societies are socially constructed,” says Boyer. “These are not driven by the sex of the person; they are gender driven and are a product of the socialization processes and how young people are raised to play different roles in society. In the earlier study, we were looking at a small number of situations where women were heads of state, and found that female leaders were no less use-of-force prone than their male counterparts. In the latter study, with a much larger experimental sample, it’s clear that women in general approach negotiation in more collaborative ways than do men.”

There are currently 20 women in the U.S. Senate and 84 women in the U.S. House of Representatives, approximately 20 percent in each branch of Congress, according to the Center for Women and Politics at the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University. In 2016, approximately 1,809 women serve in the 50 state legislatures, about 24.5 percent of all state legislators according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Internationally, women in national legislative bodies globally comprise 22.6 percent of parliaments, according to the International Parliament Union.

“We still don’t have a critical mass of women in leadership roles in many societies around the world,” Boyer says. “Some would argue that until women hold at least a third of of the seats in legislative bodies, significant change to traditionally gendered approaches to policy is unlikely to occur.”