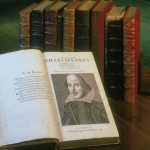

Earlier this year when a previously unknown first edition of the collected works of William Shakespeare was discovered in Scotland, the extensive media coverage demonstrated why the book known as “The First Folio” is so revered. With no known copies of Shakespeare’s plays written in his own hand, the Folio is the most direct link to the Bard of Avon, who continues to tower unchallenged above all writers in the English language.

The exhibition of one of the 233 remaining copies of the Folio, “First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare,” will be on display at the William Benton Museum of Art at UConn from Sept. 1 to 25.

The traveling exhibition is stopping at just one institution in each of the 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, to mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The tour is a partnership between The Folger Shakespeare Library, Cincinnati Museum Center, and the American Library Association.

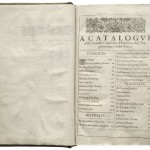

The First Folio is the first collected edition of 36 Shakespeare plays published by two of his fellow actors in 1623, seven years after the Bard’s death on April 23. The collection includes 18 plays that would otherwise have been lost, including “Macbeth,” Julius Caesar,” “Twelfth Night,” “The Tempest,” “Antony and Cleopatra,” “The Comedy of Errors,” and “As You Like It.”

Lindsay Cummings, assistant professor of theatre studies who teaches Shakespeare classes, says working on the effort to bring the First Folio to UConn helped her to rediscover the complicated process of making the book and the source of the ongoing scholarly interest in Shakespeare’s writing.

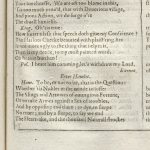

“We have no plays or poems in Shakespeare’s own handwriting, only what was transcribed for the acting companies and, later, printers,” she says. “Spelling of words could be changed because spelling wasn’t standard. We know there are typographical errors. Because it was so expensive to print, they would set out 12 copies and go over them and use pages in the book with the typos and not correct them until the next printing.”

Before the First Folio was published, several of Shakespeare’s plays were printed in the format known as “quarto” editions. Printing formats are differentiated by the number of folds in the printed sheet that resulted in variations in the text due to the size of the page. Quartos have pages folded twice in half for a smaller book and folios are pages folded just once. Depending on which printing form was used, scholars make notations such as Q1 for quarto editions, and F2 for folios, when noting text variations in the plays.

“Students often take for granted the material that’s sitting in front of them. They think somehow it was preserved and now I have it. Talking about the history of how the First Folio was made helps make the process of history very real,” Cummings says. “Just think about why a book is important. Students are used to instant information. They want to read their books on electronic devices. But it raises interesting questions to me of books as objects. Students have a different relationship with the object of a book.”

When exhibited, The First Folio is open to Act 3, Scene 1, from “Hamlet,” the page containing the soliloquy that is perhaps the best known in all of Shakespeare’s writings which begins: “To be, or not to be? That is the question.”

Cummings says Shakespearian scholars study “crucial textual variations” in the passage, but visitors to the Benton Museum will simply enjoy seeing the most famous speech in the English language in its original form.

During the month-long run of the First Folio, the Benton Museum is also offering a “Culture of Shakespeare” exhibit to complement the First Folio, featuring art on loan from the Wadsworth Atheneum, costumes from the Hartford Stage performances of Shakespeare plays, and posters designed by students from the UConn Design Center to commemorate the visit of the First Folio to campus.

UConn will also present a variety of related academic and cultural programming in its venues such as the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, libraries, and lecture halls. The activities will include a Connecticut Repertory Theatre production of a Shakespeare play, workshops for high school English teachers, a puppet adaptation of “Macbeth,” a related exhibit on “The Culture of Shakespeare” at the Benton, a musical performance, and other events. For an events listing, go to shakespeare.uconn.edu.

In celebration of the Folio’s stay at UConn, Connecticut Repertory Theatre will open their season with Shakespeare’s King Lear, which will play in the Harriet S. Jorgensen Theatre from Oct. 6 to 16. King Lear is a play that has fascinated audiences for more than 400 years and is often considered as Shakespeare’s greatest achievement. As the aging monarch resolves to retire and divide his kingdom, his family and country are torn apart in the process, and the king’s descent into madness begins. The once proud monarch is forced to wrestle with morality as he confronts his own mortality. As George Bernard Shaw wrote, “No man will ever write a better tragedy than Lear.”

For information go to shakespeare.uconn.edu.