If a man is found to have low-grade prostate cancer, there’s growing evidence to support the idea that the best course of action is nothing.

Nothing right away, that is—no surgery, no radiation—nothing other than to keep an eye on it and monitor how it progresses. Known as “active surveillance” or “watchful waiting,” the idea is that low-grade prostate cancer is likely to progress too slowly to keep pace with the remaining life expectancy of the men who have it.

“I don’t want to say that men don’t die of prostate cancer,” says Dr. Peter Albertsen, chief of UConn Health’s Division of Urology. “But a lot of older men have what we know are slowly growing prostate cancers. In the past they would die of heart disease or lung problems or something else long before their prostate cancer could kill them. That’s still true.”

A new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, on which Albertsen served as a consultant, further supports that.

From 1999 through 2009, Oxford University followed more than 1,600 men, ages 50 through 69 who were diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, and divided into three study groups. One group was treated with surgery, one group was treated with radiation, and one group was monitored under active surveillance. The study found no significant differences in prostate cancer mortality between the three groups.

“That’s huge,” says Albertsen, who is one of the world’s pioneers of active surveillance. “This is the first randomized trial ever conducted that compares surgery against radiation against surveillance in men with localized prostate cancer.”

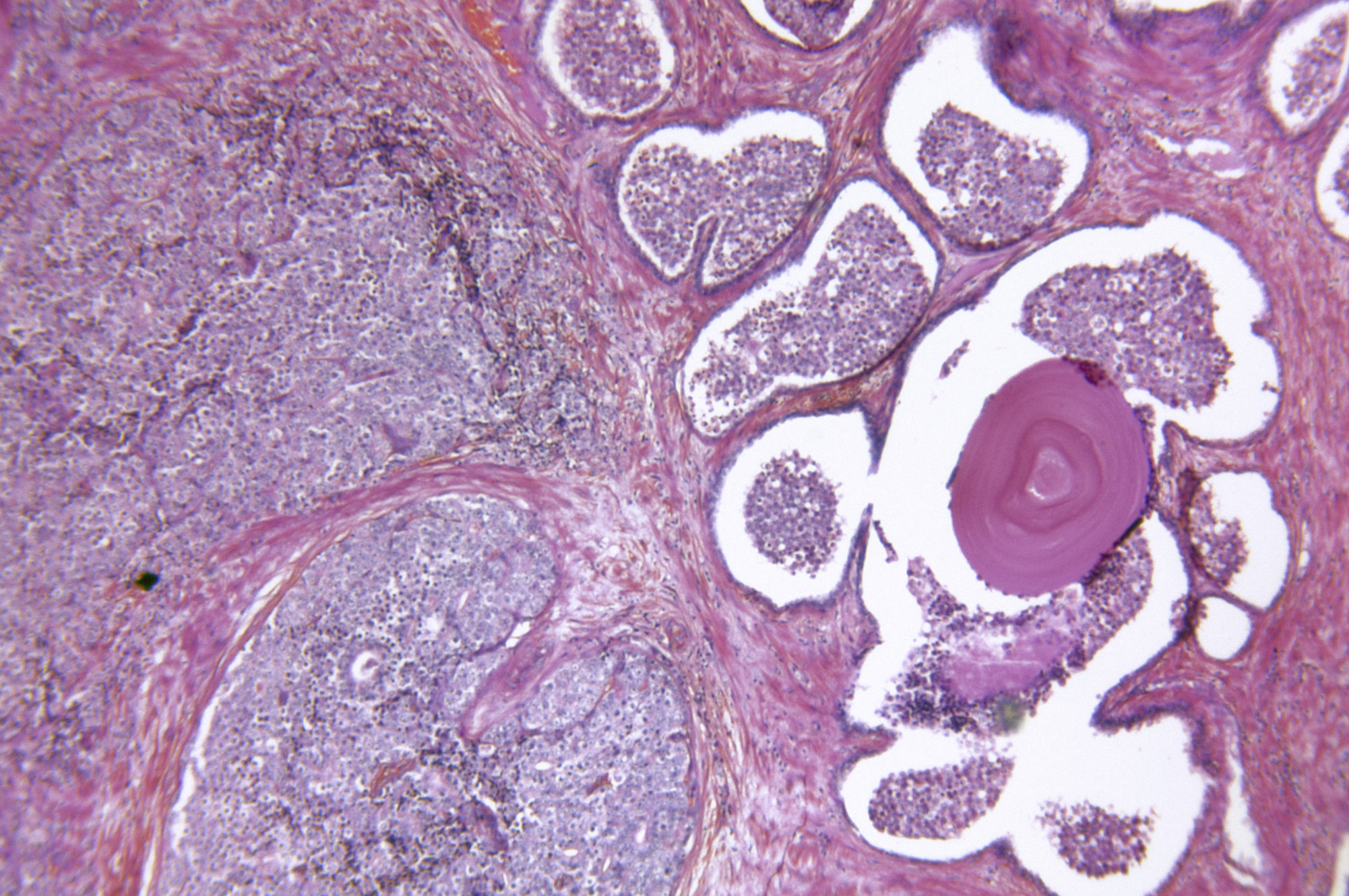

The contemporary paradigm for management of prostate cancer, he says, is a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test, a biopsy, and if cancer is found, either surgery or radiation. PSA testing has come under fire in recent years amid concerns that it may lead to interventions that may carry more risks than the cancer itself, notably erectile dysfunction or incontinence. But Albertsen says it would not be prudent to dismiss PSA testing entirely.

“For those men we find with low-volume, low-grade cancers—which is a significant portion of the population—we should be offering them active surveillance rather than intervention,” Albertsen says. “So we should be operating on the men who are destined to have symptoms or die of their cancer, which are the high-grade cancers and most of the intermediate-grade cancers, but relatively few of the low-grade cancers as proven by the New England Journal of Medicine study.”

Albertsen estimates that the demand for active surveillance in the U.S. is about 10 percent of the treated population, but in parts of Europe it’s closer to 50 percent. He says the best candidates for this approach are younger men who are sexually active.

“While they grow older, they allow us to monitor their prostate cancers so we’re not in a rush to take their prostate out,” Albertsen says. “Should they progress, then we offer the treatment, but a little later in life, when things aren’t quite as critical or they might naturally not be functioning as well—or not at all, if they turn out to be one of those cancers that were never destined to kill.”

Here at Home

Albertsen says he has about 100 patients he’s currently following on active surveillance. One of the tools he uses is multiple-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has replaced ultrasound as the imaging method of choice for this purpose.

“It has now become increasingly the standard of care throughout the world, including this country,” Alberstsen says. “It’s capable of visualizing the high-grade prostate cancers but not the low-grade.”

By definition this approach yields multiple sequences. Those include a weighted image to show detailed anatomy, a measurement of cellular density, and the vascular supply to the prostate.

In the U.K., multi-parametric MRI has supplanted biopsy as the primary screening tool. In January 2012, Albertsen went on a sabbatical to the University College London to learn about it and bring the idea back with him. He returned with the ability to read MRIs, a skill more common in radiology than urology. The UConn Health Department of Radiology started offering multi-parametric MRI later that year. Albertsen and Dr. Marco Molina, a UConn Health radiologist, read the images together.

UConn Health has had recent MRI software updates to bring state-of-the-art prostate imaging to patients. In the coming months it will add a new MRI with a 3 Tesla magnet, which Albertsen says will further enhance its capability.