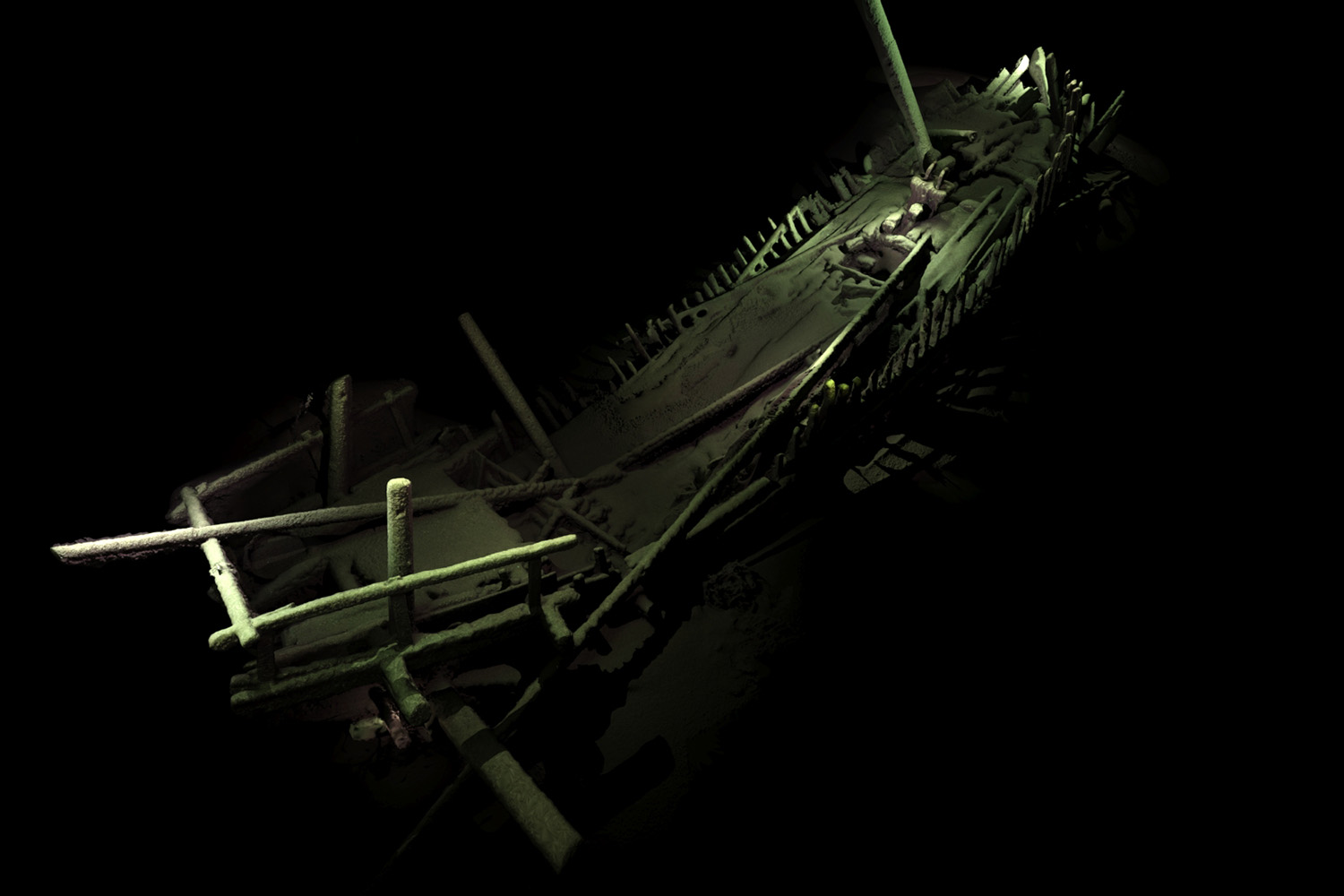

A UConn researcher is part of an international team of scientists mapping ancient underwater landscapes in the Black Sea that has made dramatic discoveries of multiple shipwrecks, including a never-before-seen medieval seafaring vessel.

Kroum Batchvarov, an assistant professor of anthropology whose specialty is nautical archaeology, is a co-director of the Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project (MAP), which is described as one of the largest maritime archaeological expeditions ever undertaken.

‘A truly thrilling moment’

While conducting their mapping in late summer using the most advanced underwater survey equipment in the world, Batchvarov and his colleagues discovered a total of 43 shipwrecks. The team had expected to see sunken ships, but were surprised at just what they found.

Batchvarov first spotted the well preserved medieval shipwreck on a screen in the control room of the expedition ship after nearly 48 hours of monitoring images from the high remote survey vehicle moving along the floor of the Black Sea.

“That was a truly thrilling moment. We spent the next six hours looking at the wreck. No one had ever seen anything like it,” he says. “We had known of it. There have been descriptions in Venetian manuscripts that survived from the 15th century describing earlier vessels. But this was the first time that we were seeing it.”

The ship was complete, according to Batchvarov: “The masts were still standing. You could see the spars [wooden poles], the yards on deck. Everything was there.”

The discovery of the shipwrecks was aided by unique conditions beneath the surface of the Black Sea known as anoxic waters, which have low salt content and dissolved oxygen, and do not support the wood-eating sea creature known as Teredo navalis, or the naval shipworm. As a result, the shipwrecks are largely intact, their wood not deteriorated as it would be in oceans in other parts of the world.

The vessels the Black Sea MAP team discovered date over the course of a millennium, from the 9th to the 19th centuries. Many were merchant ships from the Ottoman Empire between the 15th and 19th centuries, mostly from the 18th century. But the medieval ship – dating from the 13th to the mid-14th century and probably of Mediterranean origin – provides the first view of a ship type known from historical sources but never before seen.

We spent the next six hours looking at the wreck. No one had ever seen anything like it. — Kroum Batchvarov

“This is the type of ship that created the trading empires of Venice and Genoa; the type of ship used by the Crusaders,” Batchvarov says. “This is the ship type that really ushered in the modern age. What is particularly interesting is that this is the last period before the mixing of the northern shipbuilding tradition and the Mediterranean shipbuilding tradition, which happened from the end of the 14th and early 15th century.”

During the post-medieval period, when trading ships from northern Europe and the Mediterranean docked in common ports, shipwrights from each region began to adopt features from each other’s designs. The rudder, affixed to the stern of a ship for steering, was originally developed in Scandinavia; it eventually began to be used in Mediterranean vessels, which previously used only steering oars or quarter rudders for directing a ship.

Batchvarov says studying the shipwrecks can help to better understand seafaring in the Middle Ages and the post-medieval period in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Seas, and by extrapolation, in earlier times. The Black Sea was a major route for transporting goods during that time period throughout the region from Greece and Turkey to the Balkans and Russia through the Bosporus Strait, the waterway that is the boundary between Europe and Asia.

Most significantly, he says, the medieval Mediterranean-type vessel is an example of the type of ship that led to the development of larger ocean-going vessels used by Christopher Columbus and other European explorers who crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas.

“The shipwrecks are a source of information because they do inform us about the further past,” he says. “It is a symbol of the interconnectivity of the region.”

The impact of climate change in history

While analysis of the shipwrecks is ongoing, the team continues with its intended purpose, investigating the area for evidence of how humans reacted to changes in the environment in previous eras.

“We are answering an archaeological question: At what stage did the level of the Black Sea change and what once would have been marshy coastal land become inhabitable and then become inundated?” Batchvarov says, noting that the team’s findings could add to previous studies on catastrophic flooding in the Black Sea region.

There is no question there is dramatic climate change at the moment. The question is: how rapid were such changes in the past? — Kroum Batchvarov

He says there is evidence from inundated settlements from both Neolithic and early Bronze Age settlements. At least 20 are known along the Bulgarian coast. Although none has been completely excavated, extensive tests have been conducted on a number of the sites.

The research team will study layered samples of sand, mud, rock, and organic material retrieved from various locations under the Black Sea to try and determine when periods of flooding occurred. The changes in the layers of material can be used to date changes underwater similar to how rings inside a tree can date the age of the tree.

“We see about five meters of mud overburdened before we hit a layer of sand, shells, etc., that appears to be the old coastal line,” Batchvarov says. “Not only can we date it, it can tell us quite a lot about the climate change in this period, which of course is a hotly debated issue. There is no question there is dramatic climate change at the moment. The question is: how rapid were such changes in the past? This is one of the things we are going to be able to determine.”

The Black Sea MAP project is a partnership involving major archaeological institutions in Bulgaria, Britain, and Sweden, as well as UConn.

Batchvarov, a native of Bulgaria, joined the team at the invitation of Jonathan Adams, the leader of the scientific team, who is director of the University of Southampton’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology and a leading maritime archaeologist. The two researchers had previously both worked on the excavation of the 17th-century vessel, the Warwick, in Bermuda; and Adams consulted with Batchvarov on working through Bulgarian authorities for the Black Sea MAP project.

“When Jon Adams asks you to co-direct a project with him,” says Batchvarov, “it’s like Luciano Pavarotti asking you to sing. You don’t say no.”

The partner institutions include the Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the University of Southampton – the lead institution; Bulgarian Institute of Archaeology with Museum, directed by Lyudmil Vagalinski; Bulgarian Centre for Underwater Archaeology, directed by the late Hristina Angelova and now by Kalin Dimitrov; and the Maritime Archaeological Research Institute at Södertörn University, Sweden, directed by Johann Rönnby.

The international team is funded by the British Expedition and Education Foundation, and operates under permits and in full compliance with the laws of the Republic of Bulgaria, and in strict observance of the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.