By Josh Garvey

Biomedical engineering professor Ki Chon is developing a new heart monitor to identify the early signs of irregular heartbeat that can be worn throughout the day.

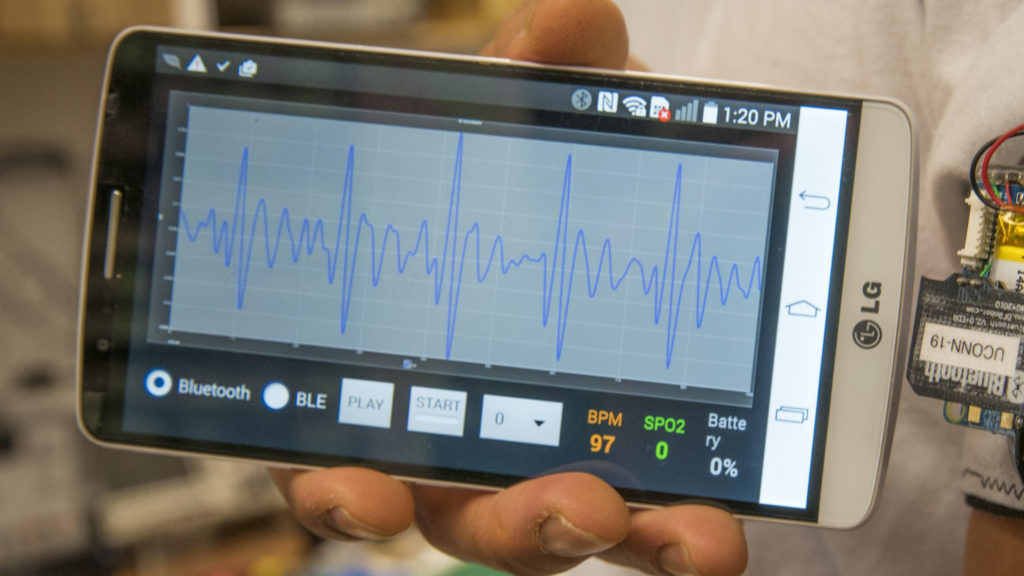

Chon and his research team are working to create a small armband that can be worn all day, without any wired connection, to monitor for atrial fibrillation over an extended period of time without disrupting a person’s everyday activities. They are also creating a smartphone app that will receive data from the sensors using Bluetooth connections.

An irregular heartbeat can be a warning sign for heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, and early detection can save lives. Atrial fibrillation, the most common type of irregular heartbeat, often begins occurring in sudden, short-lived episodes that don’t have revealing symptoms. The detection technology currently in use makes discovering these early indicator occurrences of atrial fibrillation difficult for a number of reasons, but a company started by the UConn researchers recently received funding to combine different technologies they’d created into a cohesive early detection device.

Mobile Sense Technologies was created by department head of biomedical engineering and Krenicki Endowed Chair professor Ki Chon and his postdocs and graduate students to develop new heart monitors to identify the early signs of atrial fibrillation and other types of irregular heartbeat that can be worn throughout the day. The company recently received $500,000 in startup funding from Connecticut Innovations.

“Atrial fibrillation affects millions of people and leads to thousands of preventable deaths each year,” says Chon. “With the device we’re working to bring to market, we’re hoping to make it much easier to identify early stage atrial fibrillation, which could save a lot of lives and hundreds of millions in health care costs.”

There are currently 6 million people in the United States diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, with many more going undiagnosed. Those people are five times more likely to suffer a stroke than patients without atrial fibrillation, and 33 percent will suffer a life-threatening stroke at some point in their lives. There were an estimated 88,000 deaths in 2015 from atrial fibrillation-related strokes, and 80 percent of those deaths are considered to have been preventable.

Chon and his team have already developed much of the technology needed to craft their heart monitors. They’ve recently created reusable electrocardiography sensors that can operate when wet or dry, including when fully submerged in water, and don’t cause skin irritation. These sensors can monitor a person’s heartbeat very accurately, and are the key to the armband they’re designing.

The researchers have also created a pair of algorithms that can accurately detect atrial fibrillation and can remove false positives caused by physical activity or other background noise. Chon says the team intends to create a mobile app to implement the detection algorithms from the sensor armband. The combination of the App and sensor armband would allow a person to monitor for an irregular heartbeat for a period of months.

Most of the strategies currently available to monitor for an irregular heartbeat have drawbacks that make them difficult to use for early detection. Electrocardiography machines are sensitive enough to monitor for an irregular heartbeat, but the equipment is bulky and stationary, requiring patients to actually be experiencing an irregular heartbeat at the time they see a doctor. Some of the portable heart monitors that are often used now and are usually designed for around two weeks of monitoring – called Holter monitors – require a wired connection to a monitoring device and use hydrogel-based electrodes, which can irritate the skin. Other devices are implanted under a person’s skin, making for a more invasive and expensive approach that is often used after an irregular heartbeat has been identified.

Chon says he’s optimistic about being able to create a coherent package to monitor for atrial fibrillation at the early stages.

“My team has already done much of the work,” he says. “What we’re doing now is bringing everything together into a coherent package.”