Even as President Woodrow Wilson tried to maintain neutrality for the United States as World War I erupted in Europe in 1914, Americans at home began to prepare for what appeared to be America’s inevitable participation in the battle. By the time of America’s official entry into the war a century ago this week, on April 6, 1917, land grant institutions such as the Connecticut Agricultural College were becoming an important resource for the war effort both at home and abroad.

The role of the small agricultural institution that would become the University of Connecticut during the “War to End All Wars” is the subject of the exhibition “Commemorating the Centennial,” on display at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center and the Babbidge Library from April 6 through May 15. The exhibition draws on the resources of the University Library’s Archives and Special Collections and the Library of Congress.

“I think the strength of this exhibit is showing how the war touched every aspect of life at home, and how people had to adjust to make their life possible and the war possible,” says university archivist Betsy Pittman.

The exhibition includes dozens of photographs, official military documents, artifacts, recruitment posters, military handbooks, personal correspondence, news reports, and memorabilia from life on campus in Storrs, in other parts of Connecticut, and on the European war front.

Pittman developed the exhibition with Allison B. Horrocks ’16 Ph.D., Draper Dissertation Fellow in the Humanities Institute, and Mary M. Mahoney ’12 MA, a doctoral candidate in history. The UConn exhibition is part of a series of World War I centennial activities that are part of “The Yanks Are Coming: Connecticut’s Centennial Commemoration of the U.S. Entry into World War I,” coordinated by the Connecticut State Library.

In the Dodd Center exhibition, the focus is life on the Connecticut Agricultural College campus and in Connecticut, recruitment posters for the war effort, and the experiences of Captain Dana T. Leavenworth, an estate councilor at Connecticut Mutual Life who was part of the American Expeditionary Force in France.

On campus, Horrocks says once the U.S. entered the conflict, the Connecticut Agricultural College Agricultural Extension Service began training people in food conservation and canning methods, as well as military skills. About 500 women trained in Storrs, and an estimated 30,000 people throughout Connecticut learned such skills from those trained on campus.

“They’re having a lot of short courses to bring people in to train them for specific skills on things like canning and milk testing,” she says. “There was also some activity around military skills like working with radios.”

Horrocks says one of the biggest changes was a radical shift in the student population within just a few months, with many young men leaving and more women arriving. The women were encouraged to learn specific skills that they were able to see as a wartime contribution.

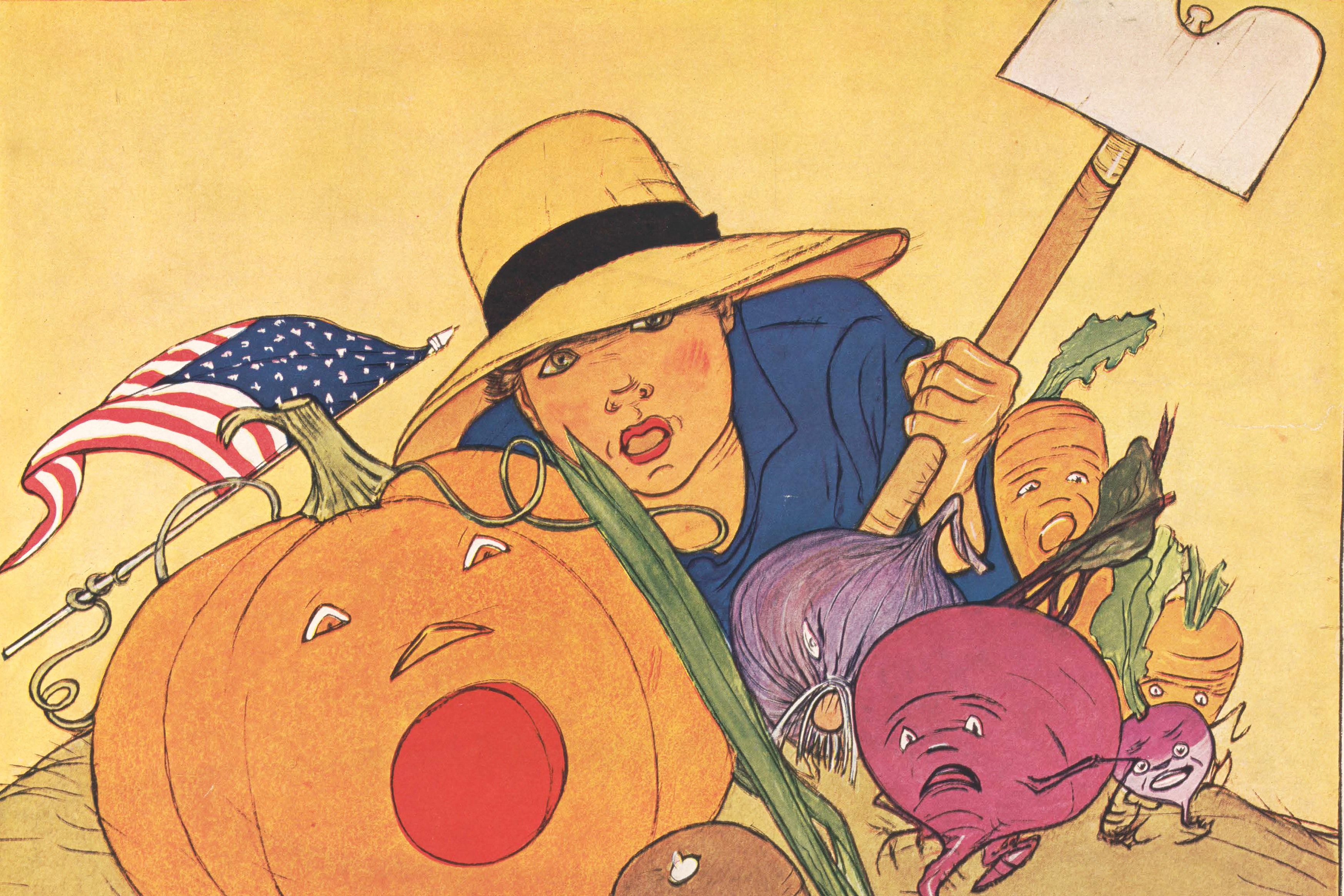

The promotion to start “Victory Gardens” throughout Connecticut and the nation is also part of the exhibition. There are news clippings describing the Junior Food Army, including children in Bridgeport, New Haven, and Stamford who grew corn and potatoes.

“What really struck me is that is happening in both urban and rural environments,” Horrocks comments. “People were very active all over the state. They’re in the cities like New Haven trying to get kids to grow gardens, sometimes in a very dense urban area.”

Recruitment posters from among the 55 in the exhibition include the famous James Montgomery Flagg image of Uncle Sam declaring “I Want You for the U.S. Army,” as well as those seeking specific skills for military service such as electricians, radio operators, and mechanics for repairing tanks. There are also American Red Cross posters –“Our Boys Need Sox: Knit Your Bit” – and promotions for buying war bonds to fund the war effort.

The Leavenworth memorabilia is from the archive of materials from one of Connecticut’s prominent families. Included in the display are a small book titled “First Lessons in Spoken French for Men in Military Service,” a pamphlet on “Military Map Reading,” and a sheet of instructions dated April 9, 1918 titled “Defensive Measures Against Gas.”

There are also handwritten letters from friends of Leavenworth. Carlton Redmond writes on Oct. 24, 1918, “I am working very hard to aid in the production of Ordnance for you boys.” Antoinette Pierce, writing on Nov. 14, 1917: “You don’t know how you soldiers are the center of all our thoughts, nor how proud we are that our defenders in these hard times are of the sort we can safely rely upon in every need.”

The Babbidge exhibition focuses on a variety of select University Archives and Special Collections materials connected to World War I – including children’s literature, sheet music, work of the Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station, photographs and nursing artifacts from the Josephine A. Dolan Collection – and the development of bibliotherapy during the war.

“Bibliotherapy is the use of books as medicine,” says Mahoney. “While that’s an idea that has existed as long as reading itself – that you can read a book and feel healed by it – World War I is the first moment we see librarians experimenting with books to apply them medicinally to treat specific ailments.”

The American Library Association and the Library of Congress joined to collect books initially just to entertain troops while they were serving in the trenches overseas. In the course of doing that, they established what would become the Hospital Library Service. Librarians working in hospitals found that in practice certain genres of books could be harmful to certain kinds of patients.

“First do no harm is the Hippocratic Oath that doctors take. It is not something you typically associate with librarians,” Mahoney says. “But the war is when they say, we have a professional obligation to assert ourselves in people’s health through what kind of books they’re exposing themselves to and we can both heal and prevent people from harming themselves.”

Hospital librarians found, for example, that when a detective story is given to someone who has tuberculosis or has a fever, the excitement of that story may raise their body temperature; or a patient suffering from shell shock could be helped by reading certain kinds of poetry or travel books.

“They start to experiment on this wide range of patients that they had access to, to see how books might be used a medicine and how that might become its own science,” she adds, noting that later formal research in this field was established by Louise Sweet, the hospital librarian at the U.S. Army General Hospital in New Haven.

Websites with more information about “Commemorating the Centennial” have been established, including one on Bibliotherapy, Dana Leavenworth, and The Land-grant College at War: A Retrospective.

The Homer Babbidge Library is located at 369 Fairfield Way, and is open from 7:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday through Friday and from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on weekends through May 6. After May 6, the hours are Monday through Thursday from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., and from noon to 5 p.m. on weekends. The Dodd Center is located at 405 Babbidge Road, and is open Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

![NEW_HAVEN_CORN_CLUB[1]](http://today.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NEW_HAVEN_CORN_CLUB1-150x150.jpg)

![JUNIOR_FOOD_ARMY_CANNING[1]](http://today.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/JUNIOR_FOOD_ARMY_CANNING1-150x150.jpg)