UConn law professor Jessica Rubin and her students are at the forefront of a new courtroom advocacy program for abused animals that is gaining ground in Connecticut and attracting notice across the nation.

Under a groundbreaking law that took effect in October 2016, judges in Connecticut may appoint a law student working under supervision or a volunteer lawyer as an advocate for justice in animal abuse cases. The advocate gathers information about the case, interviews veterinarians and others, and speaks in court on behalf of the animal and the public’s interest.

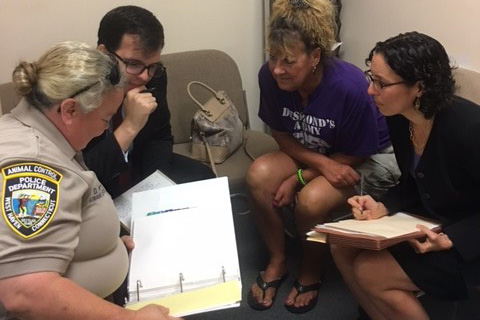

So far, the courts have assigned Rubin and her students six cases involving defendants accused of dogfighting, torturing cats, starving dogs, and beating dogs. But their work began even earlier. They were deeply involved in shaping and finding support for the enabling legislation, called Desmond’s Law after a dog that was beaten and killed by his owner in Branford in 2012. Other lawyers across the state have begun stepping up to volunteer as advocates, and a devoted group of activists, calling themselves Desmond’s Army, have been tracking and identifying cases in which an advocate is needed.

The need for change was clear to supporters of Desmond’s Law, including state Rep. Diana Urban, who sponsored the bill. Only 20 percent of the animal cruelty cases in Connecticut courts between 2006 and 2016 proceeded to trial, according to a report by the Connecticut Office of Legislative Research. Eighty percent of animal cruelty cases were either not prosecuted or dismissed, leaving no trace of the crime after the abuser completed a special form of probation. That’s what happened with the man who killed Desmond.

Yet a growing body of research shows that people who commit violence against animals are likely to harm humans as well. In one study of women seeking shelter from domestic violence, 71 percent of those with pets reported that their partner had threatened, hurt, or killed the animals, according to the American Humane Society.

In Rubin’s view, the new law has many beneficiaries. Animals gain protection, overburdened prosecutors get help, and potential human victims may be spared. And for her students, there is the additional benefit of gaining practical courtroom experience in a cause that matters to them.

Julie Shamailova, a third-year UConn Law student, says she jumped into the program because she has always been passionate about animal advocacy. But the experience has brought her even more than the satisfaction of helping animals. Her career goals are tilted toward transactional law, she said, yet she has found the program is rounding out her education with practical courtroom skills that will be useful in pro bono work in the future.

“It allows me to do things that I likely would not be doing, even one or two years into practice,” she says. “I think it’s very rare that you can argue in court, even if you’re a first-year associate, and I’m grateful to get the chance so early on.”

Other students who have handled cases include Taylor Hansen, Christopher Kelly, and Jamie Woodside. Many have taken Rubin’s Animal Law course or are involved in the Student Animal Legal Defense Fund at UConn Law.

Getting the law passed and the advocacy program started were the first steps. The continuing challenge is to ensure that judges and prosecutors use the program, and that there are enough advocates to meet the need. The Department of Agriculture now lists 11 lawyers from around the state, including Rubin, who will volunteer as advocates. She would like to see that number grow.

“The program encourages and supports vigorous enforcement of our anti-cruelty laws,” Rubin says. “For lawyers who care about animals and justice, animal advocacy work is very meaningful and fulfilling.”

Recent publicity about the advocacy program has Rubin fielding calls and emails from around the country, many from judges, legislators, and animal rights advocates who would like to pass similar laws in other states. That is a prospect she finds gratifying.

“I hope that the program can accomplish a few things — achieving justice in cruelty cases, preventing future violence, and spreading to other states so that these benefits multiply,” Rubin said. “As we progress in the ways in which we treat animals, the advocates can ensure that our justice system does the same.”