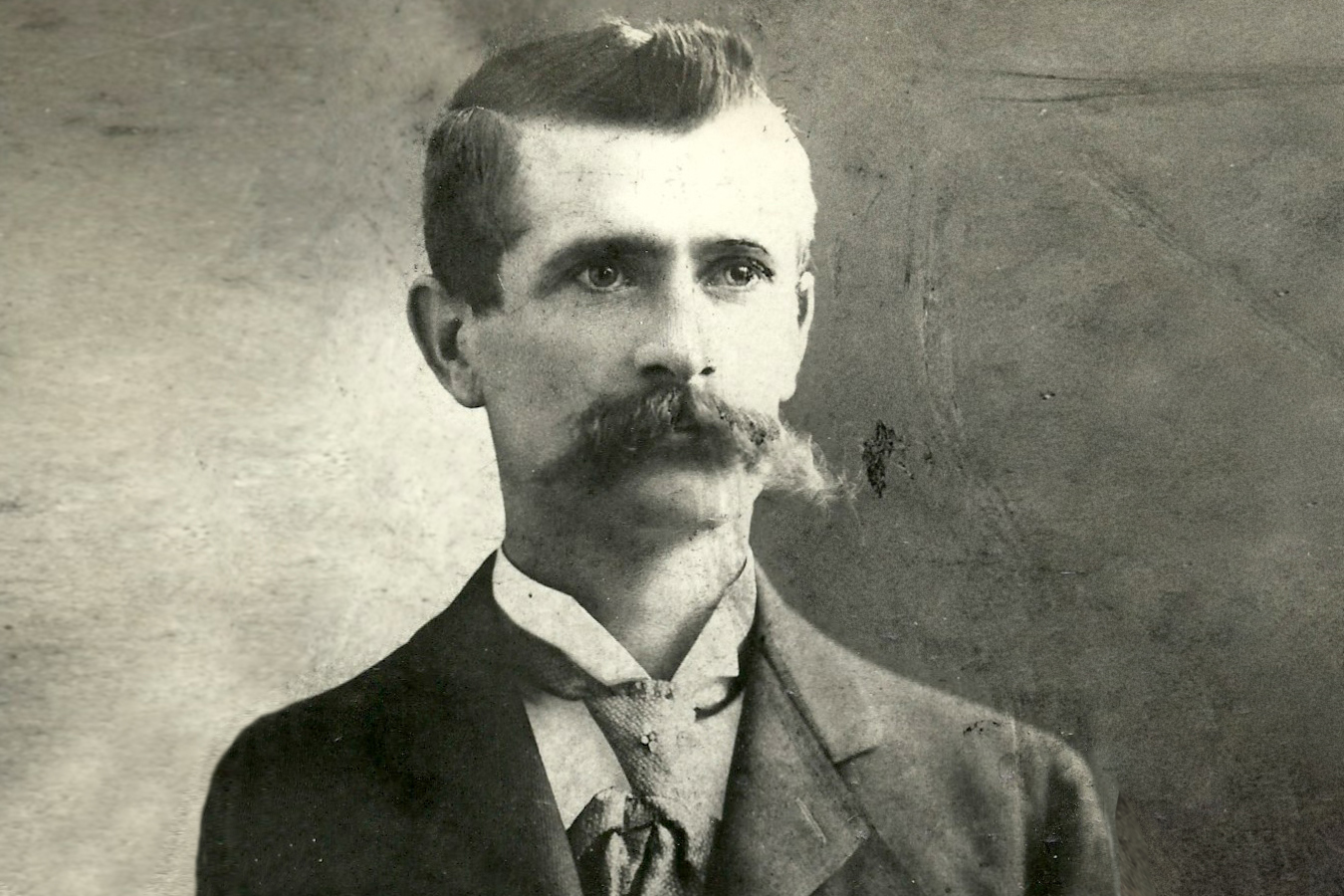

This year’s UConn Reads selection, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s short story collection ‘The Refugees,’ affords an opportunity for the university community to reflect upon and debate the hot-button issue of immigration. As part of this, UConn deputy spokesperson Tom Breen shares this reflection on his great-grandfather, an immigrant from Ireland.

This is a picture of my great-grandfather, John Evangelist Breen. He brought his family to the United States from a small village in County Kerry, Ireland, not as a refugee, but as a fugitive from justice: my great-grandfather left Ireland because he shot and killed a man.

There are always complex reasons for things like that, but the proximate cause was that he carried out the killing at the behest of a secret revolutionary organization called the Irish Republican Brotherhood. A cousin in Dublin doing genealogical research brought up the story when she contacted me in the summer of 2014: he kept his gun hidden in the thatched roof of his cottage, apparently.

It has become common … to characterize the people arriving in the United States today as fundamentally different from earlier generations of immigrants, who are idealized …

Before he died, my great-grandfather wrote a long, detailed, self-justifying account of the killing, which is how I learned most of the details. The man he shot worked for a landlord who owned residential properties in Castlemaine, a village in the southeastern corner of the country, where my grandfather grew up in a household of 21 in a building about the size of a two-car garage. The landlord had ordered a number of families to be evicted from their cottages. The IRB objected to this, and my great-grandfather’s gun was the instrument of their objection.

Fleeing Ireland after the killing, he came to the United States with his wife and children. Their first language was Irish and his most prominent skill was evading the police. They eventually settled on the South Side of Chicago, where they had more children. My great-grandfather got a job as a streetcar conductor and left his family a pension when he died; his formidable wife wore black every day after his death, and raised six children. One of their sons was awarded the Silver Star for his service in World War II, and was present at the liberation of Dachau. One of their grandchildren won an Academy Award for a screenplay about that famous Irish-built ship, the Titanic.

It has become common, in the ongoing debate about immigration, to characterize the people arriving in the United States today as fundamentally different from earlier generations of immigrants, who are idealized as plucky, hardworking, and eager to assimilate. The unspoken implication of this version of history is that these immigrants were also white, and therefore better suited to become Americans.

That this was not, in fact, the case is important to emphasize when seeing the past used as a cudgel in today’s debates. It was, after all, a son of Polish immigrants who assassinated President William McKinley in 1901, just as it was Mario Buda, an Italian immigrant to Boston, who is credited with inventing the car bomb, the prototype of which he detonated on Wall Street on Sept. 16, 1920, killing 38 people. You can still see damage from the blast in the walls of some of the buildings there today.

Those earlier generations of immigrants now seem like ideal aspirants to American citizenship only because they were allowed to come here in the first place, to live their lives and raise their children and build their institutions and join pre-existing ones, to change the country and be changed by it. Our rosy view of that experience is all hindsight.

But the people today who proudly describe themselves as Irish-American, Italian-American, Polish-American, and so forth are the descendants of immigrants who seemed just as foreign to the Anglo-Saxon Protestants of their day as people from Syria or Latin America seem to those same hyphenated Americans today.

Make no mistake, those earlier generations of “real” Americans – the New England Yankees and the New York Dutch and the stolid burghers of the Midwest – were fearful of the people coming from Ireland, Italy, Greece, Poland, Hungary, Russia, and beyond, but that fear did not prevail. And because it didn’t, we have the country that exists today, and which we take for granted, as if it had been formed without struggle and at no cost to anyone.

My great-grandfather was about as bad a prospect as you could imagine for citizenship; an impoverished member of a revolutionary organization who had killed a man. Today’s opponents of immigration would probably consider him “Exhibit A.”

But he and his wife came here anyway, and did well for themselves and their children, who in turn did well for themselves and for their children. We’re now on the fourth generation of descendants of John and Mary Breen, whose progeny have included a doctor, a union leader, many teachers at all levels of education, and people who have made intangible contributions to their neighborhoods, their towns, and their country. You’ll forgive my immodesty if I say the United States would be slightly poorer without them. I’m very grateful to live in the country that gave them a chance, and hope it remains a place of refuge for people like them from all over the world, as long as it exists.

The UConn Reads Selection Committee is launching a new initiative inviting members of the university community to submit short pieces (500 words) about their experiences with immigration and/or immigrant pasts. Following a brief review process, the selected pieces will be featured on the UConn Reads website. Please direct all submissions and queries to Cathy Schlund-Vials (cathy.schlund-vials@uconn.edu).