Landscape architecture is not a subject commonly associated with refugee settlements. But in a field of study where resilience is often applied to help fortify coasts against erosion or to safeguard habitats against loss, UConn landscape architecture researchers have begun using their expertise to encourage resilience in a different form.

The project began when Ph.D. student Tao Wu and some undergraduate researchers started exploring creative ways they could apply landscape architecture concepts to address some of the bigger social justice problems of the world. They started with the question, what happens when conflict displaces millions of people from their home country, as is the case with the current Syrian refugee crisis? Where do they go? What conditions are they living in? How long are they in these settlements?

Wu says what they found out was eye-opening, and served as inspiration to think outside the box.

They found that many refugees live far from cities, disconnected and out of sight, often in very harsh or undesirable areas, and sometimes even surrounded by barbed-wire fences patrolled by armed guards. These locations make it difficult or impossible for the refugees to work or go to school and contribute positively to the local economies, all circumstances that reinforce the idea that refugees become an economic burden to the areas where they resettle. Often, they live in these conditions for years.

Beyond economic concerns about taking in refugees, some host countries worry about an increase in the crime rate, which she says is unfounded. Consulting with Kathryn Libal, director of the UConn Human Rights Institute, Wu found the opposite was true: Crime rates are in fact lower, and there is a desire by the refugees to integrate and not be isolated in their new communities.

This is where Wu and the team saw the opportunity to instill resilience through their design.

“We wanted to find a new way to approach refugee settlements, and to find a way to enable the refugees to integrate and be a positive power in the communities where they are living,” she says.

The proposal they developed was recognized as innovative at a recent poster session at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture meeting at Virginia Tech, when it won the CELA Fellows Award of Excellence.

“[The judges said] they had never thought of applying the concept of resilience to a social cause in this way,” recalls Kristin Schwab, associate professor of landscape architecture.

A Novel Approach

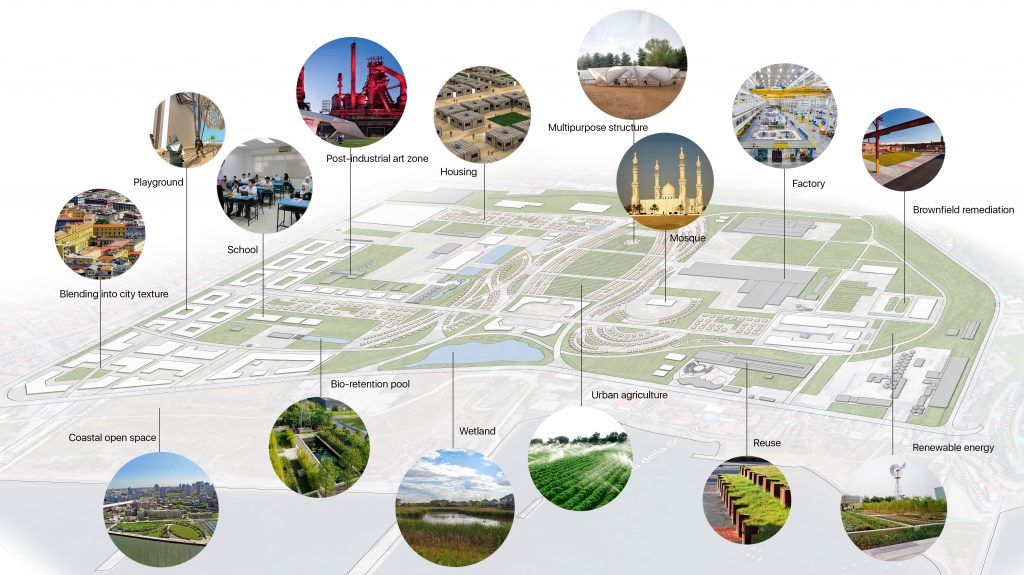

Wu’s proposed project starts with an existing brownfield, adjacent to a local community in Italy that has been in the process of revitalization since the mid-1990s. Brownfield revitalization takes former industrial plots, which may harbor industrial residues, and makes them safe and habitable once again. The revitalization process can be expensive and labor-intensive, and thus can take a long time to complete. The researchers propose approaching the degraded site with a strategy that will check multiple boxes, in hopes of achieving multiple, positive outcomes.

The first step is to involve the refugee community, in cooperation with the local community, in completing the remediation, which can speed up restoration of the site.

Restoring a brownfield not only improves the area for locals, but also instills a sense of pride and community for those who will live and work there.

The cooperative process is also a strategy to combat the perception that refugee aid adds economic stress to a community, says Wu. Instead, helping to revive a resource in an area where there is a pre-existing need shows that a refugee population can be an asset to the community.

Once remediation is complete, the proposal involves a layered approach to constructing buildings and other design elements, including plenty of green spaces, such as a wetland, an agricultural area, and a natural, wooded buffer area. Some of the site’s existing industrial structures will be saved and reused, a reminder of the past, present, and future of the site.

Besides bringing beauty to the previously abandoned site, the design also involves vital components to encourage cultural exchange and social resilience, including a community center, cultural exchange center, an art gallery, and a science center. Other necessary amenities are accounted for, such as schools, hospitals, and office buildings, to provide the refugee community with what they need to live a lifestyle that approximates what they were forced to leave behind.

Schwab says another important aspect of this model is that the community is designed to accommodate a fluid, in-need population of any background. By integrating the inhabitants into the surrounding community and giving them access to jobs and services they need, the refugee population becomes a transitional community.

“This community is an asset locally, both ecologically as well as economically,” says Schwab.

The researchers hope this project will serve as a model for other in-need communities facing homelessness, disabilities, or other challenges to find their way back into the world.