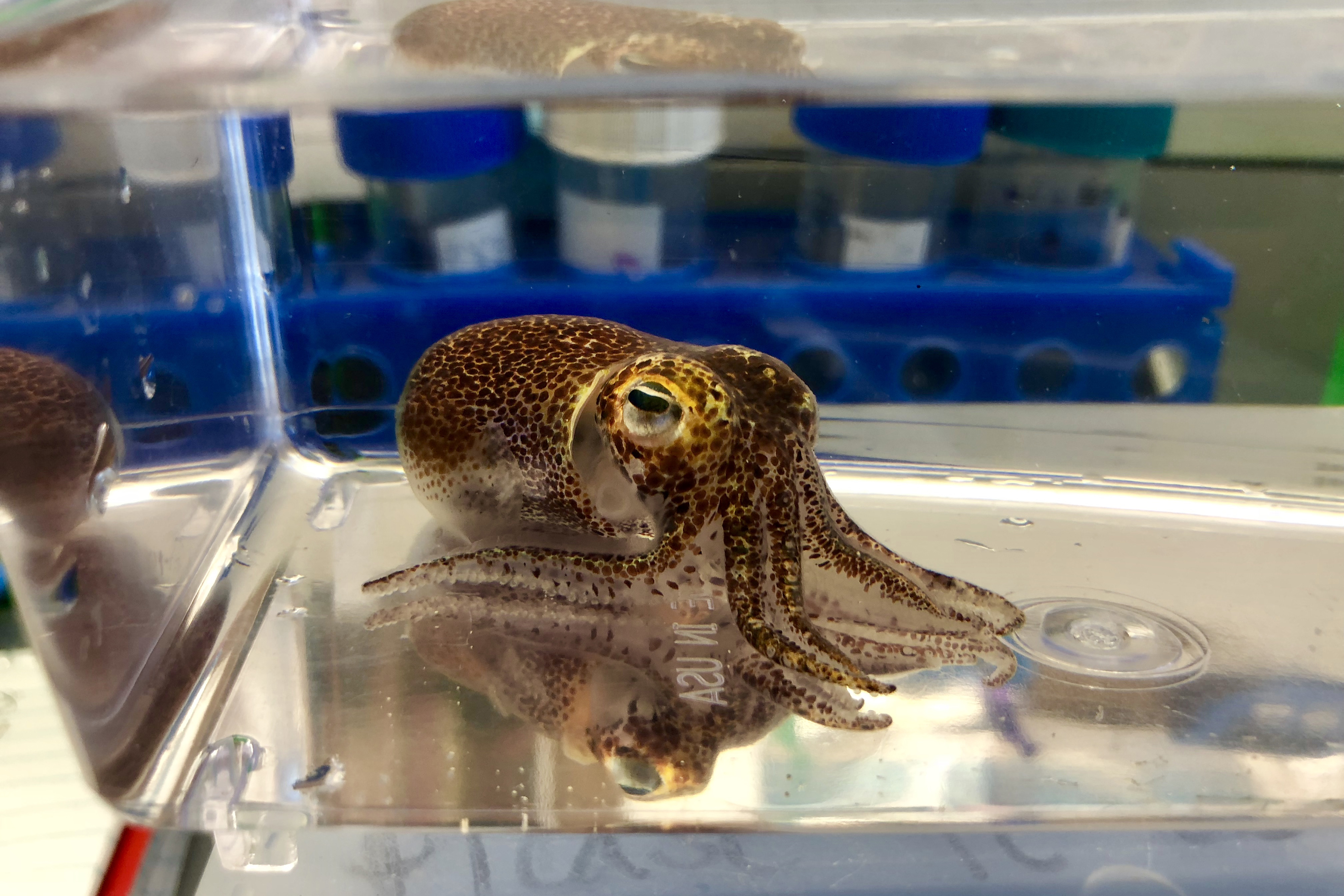

Bacteria, which are vital for the health of all animals, also played a major role in the evolution of animals and their tissues. In an effort to understand just how animals co-evolved with bacteria over time, researchers have turned to the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes.

In a new study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an international team of researchers, led by UConn associate professor of molecular and cell biology Spencer Nyholm, sequenced the genome of this little squid to identify unique evolutionary footprints in symbiotic organs, yielding clues about how organs that house bacteria are especially suited for this partnership.

The first squid genome was sequenced by Nyholm, along with Jamie Foster of the University of Florida, Oleg Simakov of the University of Vienna, and Mahdi Belcaid of the University of Hawaii. The team found several surprises, for instance, that the Hawaiian bobtail squid’s genome is 1.5 times the size of the human genome.

By comparing the genome of E. scolopes to its cousin, the octopus, the researchers show that the common ancestor of both the octopus and the Hawaiian bobtail squid went through a major genetic makeover, reorganizing and increasing the genome size. This “upgrade” likely gave the cephalopods opportunities for increased complexity, including new organs like the ones that house bacteria.

“The Hawaiian bobtail squid has served as a model organism for studying symbiosis for over 30 years,” notes Nyholm. “Having the genome will help researchers who study these interactions, as well as those studying diverse areas of biology, such as animal development and comparative evolution.”

Microbes are major drivers of the evolution of animals and their tissues. — Jamie Foster

Many animals have organs that house bacteria. The human gut houses trillions of bacteria that play important roles in digestion, immune function, and overall health. Understanding how these relationships are maintained by identifying genes that help animals cooperate with bacteria lays the groundwork for furthering knowledge of the human body. The Hawaiian bobtail squid is an excellent model for identifying these genes because of its symbiotic relationships with beneficial microbes, and its use by a number of scientists to study communication between bacteria and animals.

The Hawaiian bobtail squid has two different symbiotic organs, and researchers were able to show that each of these took different paths in their evolution. This particular species of squid has a light organ that harbors a light-producing, or bioluminescent, bacterium that enables the squid to cloak itself from predators. At some point in the past, a major “duplication event” occurred that led to repeat copies of genes that normally exist in the eye. These genes allowed the squid to manipulate the light generated by the bacteria.

Another finding was that in the accessory nidamental gland, a female reproductive organ, there was an enrichment of genes that are “orphan genes” or genes that have only been found in the bobtail squid and not in other organisms.

“Squid and octopus showed very unique genome structure, unlike in any other animals,” says Simakov, “corroborating previous reports of their unusual nature and complexity.”

Foster notes that teasing out these unusual and complex details is directly applicable to the study of other bacteria/animal relationships.

“Microbes are major drivers of the evolution of animals and their tissues,” she says. “The results of our study have helped identify the ‘origin story’ of those tissues that house an animal’s microbes, and will help tease apart the genetic processes by which these different types of innovation can happen in animals.”

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant IOS-1557914, and also by NIH Grant R01-AI50661, NIH Grant R01-OD11024 Q:21, NASA Space Biology Grant NNX13AM44G, NSF IOS 1557914, and the Office of the Vice President for Research at UConn, and the Austrian Science Fund Grant P30686-B29.

Institutions also involved in this study include University of California, Santa Barbara, University of Lyon, Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Washington University, and University of California at Berkeley.