Throughout history, the most notable portrait artists have been men – masters such as Rembrandt, da Vinci, Velazquez, van Eyck, Raphael and, as photography began, John Singer Sargent. They painted men who were rich, powerful, and famous.

In 1901, an ambitious young woman who had studied painting and worked as a staff artist for a new magazine named Vogue, returned to the United States after four years of mentoring in the Paris studio of the sculptor Frederick MacMonnies, intent on establishing herself as a portrait artist.

Over a 40-year career, Ellen Emmet Rand (1875-1941) painted more than 800 portraits of business leaders, leading intellectuals, politicians, and society women, winning critical praise and becoming one of the most prolific portrait artists of the 20th century. Fifty-nine of her portraits are the focus of “The Business of Bodies: Ellen Emmet Rand and the Persuasion of Portraiture” at The William Benton Museum of Art.

The exhibition includes 23 of the 38 Rand portraits owned by the Benton, along with family photographs, illustrations, and personal diaries with sketches from the Rand Collection in the Archives and Special Collections section of the Homer Babbidge Library. Also on display is clothing from UConn’s Historical Costume and Textile Collection curated by Lynne Zacek Bassett, along with Rand portraits from private collections and museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Britain Museum of Art, and Harvard University.

“I like to think of Ellen Emmet Rand as one of the most important female artists that you’ve never heard of before, in terms of the fact that if there was anybody in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s who was rich enough and famous enough to sit for her, they did,” says Alexis L. Boylan, curator of the exhibit who is an art and art history professor and associate director of the UConn Humanities Institute.

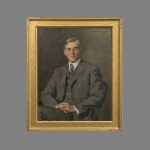

Among the notable figures in the Benton exhibition are portraits of mezzo-soprano Susan Metcalfe Casals (the wife of cellist Pablo Casals), Mary Pauline Foster du Pont (wife of U.S. Sen. Henry A. DuPont of Delaware), pioneering social worker Ida M. Cannon, and Connecticut governor John H. Trumbull. Also included in the exhibit is a portrait of Charles Lewis Beach, the fourth president of UConn, whose personal art collection would eventually become the foundation for establishing the Benton Museum of Art.

Boylan describes Rand’s life and career as “totally unique and even radical in some facets, and then also deeply typical in regard to the kinds of work/life tensions most 20th-century American women had to face.” At the age of 4, Ellen Emmet showed great artistic skills. Despite financial hardships resulting from the early death of her father, an extensive network of family and friends encouraged her to study art. In 1892, while attending the summer art school on Long Island led by the American impressionist William Merritt Chase, the 16-year-old artist’s work was noticed by the editor of a newly launched magazine, Vogue, who hired her to be an illustrator. This allowed her to help support her mother and siblings financially. In 1897, her mother moved the family to England, but after consultation from her cousin, the novelist Henry James, and a letter of support from Sargent, Emmet left for Paris to study with MacMonnies.

Upon her return to the United States, she won commercial praise for her portraits of the nation’s leading figures, working in a studio in Washington Square Park, New York City. As noted in a thesis paper written by Emily M. Mazzola MA ’15, in 1902, just a year after returning to America, Emmet received the first one-woman exhibition at Durand-Ruel Gallery in New York.

Mazzola writes: “Four years later she broke another barrier for female painters, earning a solo exhibition of 90 canvases at Copley Hall in Boston, an honor she shared only with Claude Monet, James McNeill Whistler, and John Singer Sargent.”

In 1911, when she was 36, Ellen Emmet married William Blanchard Rand and the couple bought a horse farm in Salisbury, Connecticut. She soon had three sons, but continued to work by spending the week in New York painting and returning to Connecticut on the weekends.

Boylan says Rand’s portraits evolve over time, a reflection of her training and the influence of the growth of photography in the 20th century. Painted portraits historically contain backgrounds that reflect some of the interests of the subject, while early photo portraits had minimal background details.

“When she first arrives back from studying in Paris her portraits are bit more conventional, in the sense that they have a 19th-century look,” Boylan says. “She turns away from that around 1900. You do get a real sense of the personality and person in her portraits. Painting is beginning to pick up on and model some of the conventions of photography, and I think we see that in her later works.”

From her days as an illustrator at Vogue, which began as a fashion magazine for both men and women, Rand was often recognized by critics as having a particular talent for painting men.

“She loved a good-looking man. She excelled and seemed to find pleasure in making men into the best version of themselves,” Boylan says. “She married a man who was very good looking, and wrote [in her diaries] about how good looking he was. I think it’s another element we don’t often talk about, but it’s very typical when we talk about male painters. If you go see a Picasso exhibit, it’s walls and walls of women that he had affairs with or was married to. We speak easily about the female form as a source of desire and/or inspiration for straight male painters. I think what the exhibition hints on is that Rand also had appetites, and we see some of those appetites quite literally in her paintings.”

As visitors to “The Business of Bodies” will find, there is one distinctly different part of the exhibit in a corner of the large East Gallery – an empty frame with a text block inside, which represents the portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Rand painted in 1934 during his first term. Adjacent to the empty frame is a newspaper photo of Roosevelt and Rand in Hyde Park seated in front of the portrait, with the artist in her smock holding a paint palate and brushes. Rand was the first woman to paint a presidential portrait. Elaine de Kooning became the only other female presidential portraitist, painting John F. Kennedy.

According to Boylan, Rand knew Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt socially before any of them were married, and the artist petitioned the First Lady for the opportunity to paint the president, hoping such a portrait would further cement her historic legacy. The painting hung in the White House for 11 years.

Following Roosevelt’s death near the end of World War II in 1945, all of his papers and materials were send to Hyde Park, where FDR had directed his presidential papers to be sent. For complicated and somewhat mysterious reasons, the portrait also was sent to the Roosevelt family home, removed and replaced from the official White House collection.

In 2004, Rand’s grandson, Peter Rand, went to the FDR Museum and Library at Hyde Park and asked to see his grandmother’s painting and was told it was “missing.” There was no indication of what had happened to the presidential portrait.

“Most likely it was in a traveling exhibition, was returned, stayed in its crate and then at some point was thrown out,” Boylan says. “The empty frame serves to highlight the most important Rand painting that we can’t show you anymore. Rand should have had a solid and unmovable place in the story of American art and history, but instead her name and art got lost. This show seeks to remedy that erasure.”

Boylan adds that her goal for preparing the exhibit of Rand’s paintings was to have visitors think more seriously of portraits as a complicated art form.

“We have to think about portraits as a competition between the patron’s idea of who they are, the artist’s idea of who the patron is, and the artist’s own identity,” she says. “Seeing all of these balancing and competing ideas is fascinating.”

Next spring, a new book of essays about Rand edited by Boylan will be published by Bloomsbury Press, titled Ellen Emmet Rand: Gender, Art, and Business.

Listen to a UConn360 podcast interview with Boylan, recorded at the Benton Museum:

“The Business of Bodies: Ellen Emmet Rand and the Persuasion of Portraiture” continues at the William Benton Museum of Art through March 10. Regular museum hours are Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and weekends from 1 to 4:30 p.m. For more information go to benton.uconn.edu.