Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of History Frank Costigliola, a specialist in U.S. foreign relations, is currently writing a book about former U.S. ambassador to Moscow George F. Kennan and his complex attitudes toward Russia. Costigliola spoke with UConn Today about the historical context of U.S. foreign policy, drawing upon his current work and his earlier book, Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations (Cambridge University Press).

Q. In your writings about George F. Kennan, who was pivotal in establishing policy toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, you point out that despite the policies he outlined in the document known as “The Long Telegram,” he later felt containment of the Soviet Union would be better served with a re-engaged dialogue with Moscow. President Trump appears to want to do that now.

A. Kennan was always interested above all in American interests. It’s one thing to improve relations with Russia, which I overall favor, but it’s quite another thing to sacrifice truly vital American interests in doing that. It’s absolutely unacceptable for the Russians to interfere in our elections. That is much more aggressive than anything that the Soviet Union did to the United States during the Cold War. It’s just outrageous behavior. For Trump to excuse such interference violated America’s national interest in a basic way.

We as Americans may disagree over policy – over, say, the level of taxes, restrictions on abortion, and so forth – but interference in our elections is an attack on our basic institutions, on our core values, which should be held sacred. There should be no disagreement over the seriousness of Russia’s attack on our democracy.

Q. Agreements and partnerships with our allies – including the Paris Agreement on global warming, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Trans Pacific Partnership, and others – are being broken up by the Trump Administration.

How are you looking at these changes in the post-World War II alliances of the United States?

A. I think it’s extremely unfortunate. What President Trump has done is to escalate tensions that were already present in the Western alliance. He’s done so in an extreme way. It’s generally dangerous for Washington not to work with allies. By allies, I mean nations that are powerful in their own right, that have their own point of view, and that therefore can venture a difference of opinion – not allies that are just satellites of the United States. It’s particularly dangerous to go to war on our own without at least the verbal support of nations that have values similar to our own. Generally, when the U.S. has gotten into wars accompanied by such allies as Britain, France, Germany, and Canada, the United States has done well because the rationales for war and the strategies were threshed out in advance.

There have been other conflicts where we went in alone, and the results were disastrous. For example, in the first Gulf War of 1990-91, President George H. W. Bush assembled a large coalition of many partners, including Arab nations and European allies. It was a well-thought-out campaign, it remained limited, and it achieved success. The second war with Iraq, in 2003, was far different. Washington lacked the cooperation of most major allies because most truly independent nations remained independent; and in a variety of ways, Washington’s going it alone led to a war poorly thought out in terms of insufficient troops to secure the country, unclear political objectives, and woeful cultural ignorance. Although the Americans overthrew Saddam Hussein – that was the easy part – they found themselves with a broken Iraq. The U.S. ensnared itself in a long struggle that depleted our finances, morale, and standing in the world.

Q. At the recent security conference in Germany news coverage reported that Chancellor Angela Merkel gave a strong, well-received statement about the situation regarding the Trans-Atlantic Alliance, and that the remarks by Vice President Pence by contrast were met with silence. There is also the situation in the European Union with Britain and the Brexit vote. Some are feeling it is like the breakdown among nations in the 20th century that led to two world wars.

A. It’s important not to exaggerate the differences that have persisted over the decades between the United States and the European Union. While the two units are economic rivals and have some political differences, they also share core beliefs and values, which is a very important matter. We also have shared political interests. In terms of friends in the world – the nations we want to be friends with and should be friends with – the European Union ranks high.

Of course, there can be tensions among friends, as there can be within a family. But I don’t think there are fundamental differences between the United States and the major nations of the European Union. Indeed, we need each other to bolster our common democratic institutions.

Q. What also comes to mind is the subject of trust, which was the undertone of the security conference. Comments were attributed to a senior German official indicating that the European Union can no longer trust the United States.

A. There was a disturbing statement from a commentator that most Europeans trust China and Russia more than the United States. It was sad to read that statement. Trust is built up over time. Trust requires each partner in a relationship to maintain a pattern of honoring agreements and acting within accepted norms. The United States should be regarded as dependable and hence trustworthy. That’s a very valuable asset to have in foreign affairs.

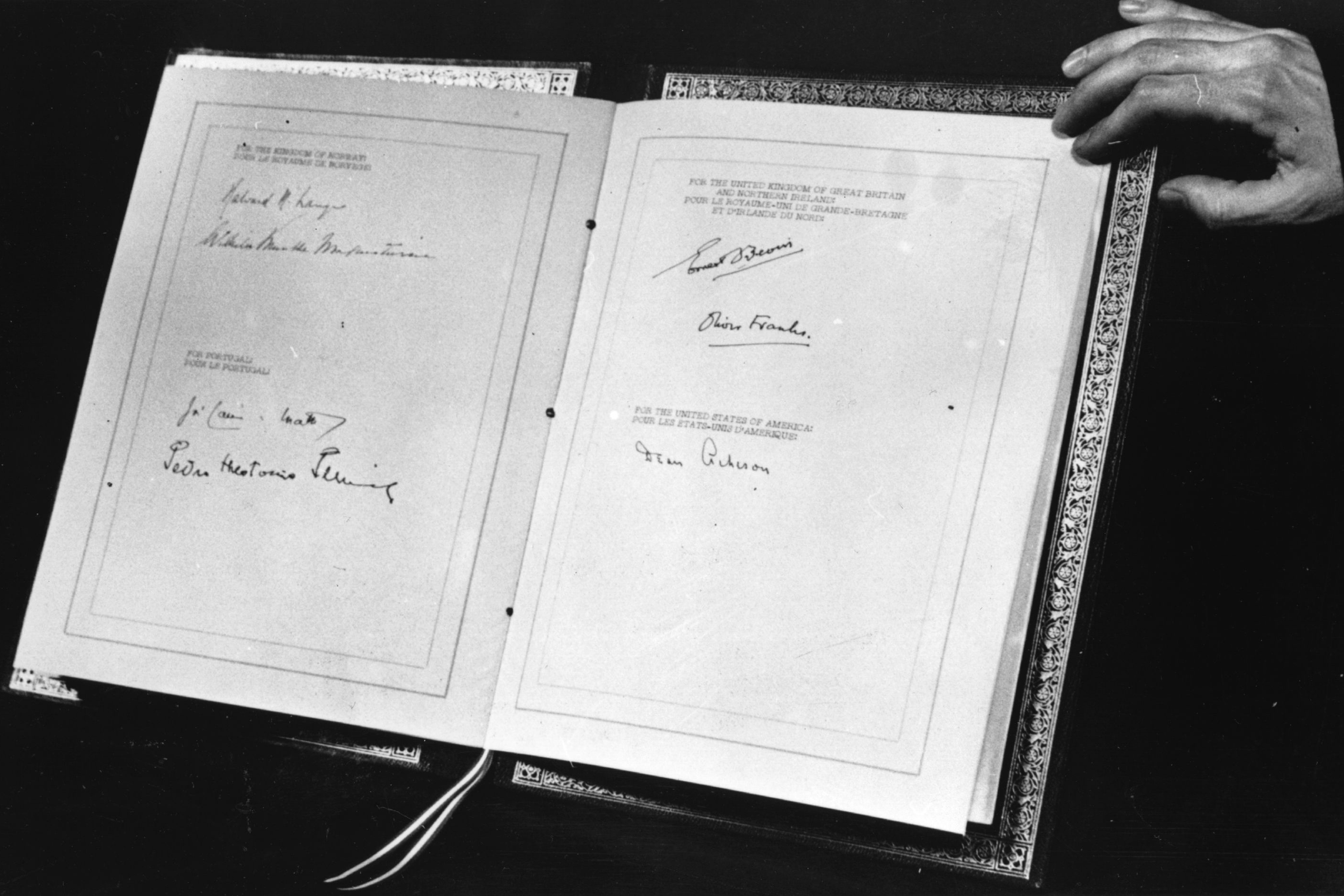

One of the greatest achievements of U.S. diplomacy after World War II was bringing together, in the NATO alliance, nations such as France, Germany, and Italy that had only recently been enemies with each other. Washington linked those countries together in an integrated military force headed by an American general. It was an enormous achievement to defuse the enmity among those nations and unite them in a common front against the Soviet Union. It was brilliant diplomacy. It required gaining the trust of these countries, while also asserting American influence and leadership. We had really talented leadership in people like John Foster Dulles, Dean Acheson, and Dwight Eisenhower. They forged an alliance that’s lasted for 70 years. It’s a tremendous achievement; and to disparage NATO and talk about leaving it grievously sacrifices America’s national interests. NATO is not a charity; it’s a vehicle for American influence. To look at NATO as a gift or favor to other nations misses the point of what has been achieved at a relatively low price.

Q. Following the Trump Administration, whether in two years or in six years, how can the United States build trust?

A. A lot depends on whether it’s two or six years, and on who the new president and her or his team will be. It’s commonly said that nations don’t have permanent friends, they have interests. There’s a basic commonality of interest between the United States and Western Europe in many matters. If the Trump era lasts only another two years, a concerted effort by a new American administration could rebuild those ties.

Nations come together not by accident and not just through effort; they have to have common interests. That’s why our relationship with Russia has been stormy over the decades, regardless of the form of government there. While we do have common interests with Moscow, we also have differences in interests that tend to divide us. Similarly, with our relationship with China, there is both some commonality of interest and some differences.

One has to consider the details in controversial issues. For example, the Trans Pacific Trade Agreement was pushed by the Obama administration as an effort to contain Chinese economic interest and influence. With the United States repudiating the agreement, that allows China to become more influential. It is bizarre in a way to portray Trump’s polices as “America First.” He promotes a vision of America as an inward-looking, not very adaptable or successful country.