Officials at the Department of the Interior, which oversees the U.S. Geological Survey, have asked a federal advisory committee to explore how putting a price on remote sensing data gathered from a satellite called Landsat might affect scientists and other users; the panel’s analysis is due later this year, with a decision also expected this year.

In a paper recently published in Remote Sensing of Environment, Zhe Zhu, assistant professor of natural resources and the environment, and co-authors say the possible policy change would significantly impact researchers who rely on remote sensing data from Landsat. At the moment, this data is free. Numerous research groups at UConn currently rely on Landsat in one way or another.

Reversing the open-source data policy will be like going back to the dark ages. — Zhe Zhu

Zhu spoke with UConn Today to explain the potential impact of such a policy change. Revoking access to this valuable open source data would result in immeasurable repercussions, he says. Read Zhu’s commentary in The Conversation.

Q. What is Landsat?

A. Landsat is a government-funded satellite program that not many people have heard of, but it is ranked as the third most important satellite in terms of its benefits to society, science, and technology. It ranks only after GPS and weather satellites.

However, any scientist doing work involving remote sensing likely relies on Landsat for data. The satellite circles the earth every 16 days, and though the resolution is 30 by 30 meters per pixel, the frequency of data gathered on a single point is important for monitoring environmental changes, such as deforestation, urbanization, fire, etc.

The resolution is not as high as, say, Google Earth, but those images are gathered and made public every few years. Again, Landsat orbits and gathers data every 16 days. Landsat is probably the top-ranked Earth observation satellite in the United States.

Q. Why is it so important that Landsat data remain open source?

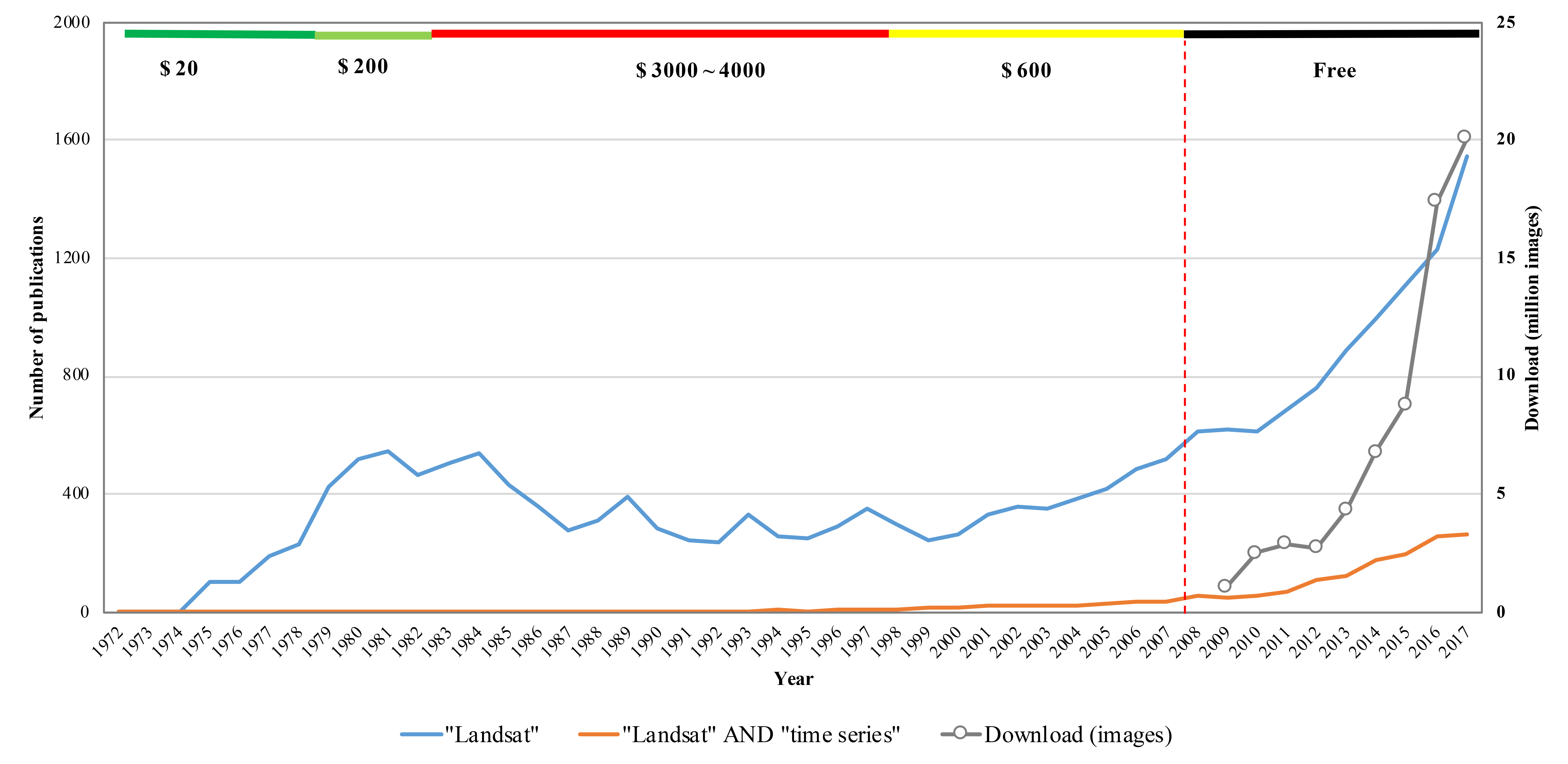

A. Landsat data is hugely important for society, science, and technology. When the satellite program was first launched in the 1970s, it was not open source. If you refer to the figure below you can see that with price increases, the amount of publications also fluctuates. Price goes up, publications go down.

But in 2008, Landsat data became open source, and the amount of publications using Landsat data skyrocketed.

But in 2008, Landsat data became open source, and the amount of publications using Landsat data skyrocketed.

In the 1980s, there were big decisions to be made: do you get one Landsat image or another piece of equipment?

The prices in the figure refer to the price per Landsat image; remote sensing research relies on monitoring changes over large areas over extended periods of time, and therefore requires thousands or even millions of images. If a single image is going to cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, that will have a huge impact on remote-sensing research.

Q. What is the argument to reverse this policy?

A. Perhaps decision makers see this as a way to generate revenue. However, as you can see in the graph, when you charge for data, people will stop using it. It becomes cost prohibitive.

Someone published a paper – that is referenced in our publication – estimating the total value of this data at approximately 1.7 billion dollars for the United States and around 400 million dollars for international users. This was based on figures from 2011, very early on in the open source timeframe. With the continued climb of publications since 2011, those values are likely to be much higher now.

But in fact, the value would drop, because no one will pay so much for data. Likely, people will not use Landsat, and will turn to other similar satellites, such as Sentinel-2. Though you can charge, the benefit to all those sectors that use it will be gone, because we simply will not be able to do a lot of things we are able to do right now.

Q. What impact will reversing the open-source data policy for Landsat have on scientific research?

A. Reversing the open-source data policy will be like going back to the dark ages. Landsat users feel this would totally change what everyone who relies on this data is doing.

The graph is very telling. Usage/publication goes down when the price goes up. When it was open source, the data climbed steeply.

The types of research Landsat is making possible are extremely important, especially now. So much global work has come out of this free data policy.

Right now we can do global mapping of forest loss, urbanization, surface water fluctuations; and we use thousands of images of the same location to see the changes over time. If there’s a charge for data, researchers would not be able to pay for the Landsat images they need.

Q. Are there other repercussions that could come out of the proposed change in policy?

A. Landsat is the first one to have this open data policy. After the open-source policy came into effect, the European equivalent – called the Copernicus satellite – followed by allowing that data to be open source too. We are worried that Copernicus will follow the policy reversal, and start charging for data again as well.

Copernicus is important because the more often you look at the same location, the more you are able tell what is happening. With both Sentinel-2A & 2B and Landsats 7-8, we can get 10 to 30 meter resolution observations every two to four days for all global land, for free. That is a huge amount of valuable data.

Since the data became open source in 2008 – so relatively recently – we are just entering this world of free data, but that could all change in the future. Going forward, we need to make people aware and encourage them to do whatever they can to keep this open and free data policy.

We need to get this information out before the decision is made. We need to let everyone know the data needs to stay open source. We made our paper open source, of course, because we need to get the word out. It’s a call to action. A reversal would be hugely detrimental to scientific research.